Book Review: Art Historian Bernard Berenson — Reinvention as the American Dream

Rachel Cohen devotes little space to Bernard Berenson’s art historical methodology, now largely superseded by modern approaches. She relates Berenson’s less admirable qualities without judging them. Her readers may not be so generous.

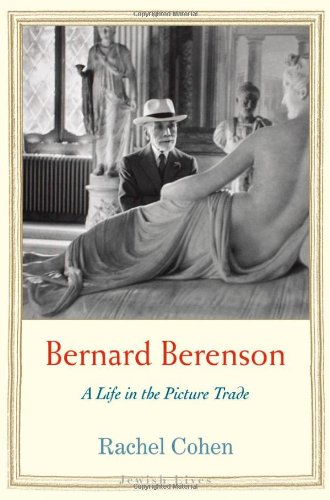

Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade, by Rachel Cohen. Yale University Press (Jewish Lives), 344 pages, $25.

By Peter Walsh

Art historians do not, as a rule, inspire even one biography. The big exception, Bernard Berenson, legendary connoisseur and authority on Italian Renaissance painting, has rated more than half a dozen. There are also several memoirs, monographs about Berenson’s relationship to several of his many friends and associates, Berenson’s own diaries and autobiographical writings, some 40,000 of his letters (hundreds of them collected into published volumes), unknown numbers of scholarly articles and dissertations, many pages devoted to him in other people’s biographies, festschrift pieces and catalogue essays about his life and method, and characters based on his personality and career in at least two novels by famous authors.

All this for a man whose own books are not much read any more, even by art historians, and whose approach to art now seems more quaint than cutting edge.

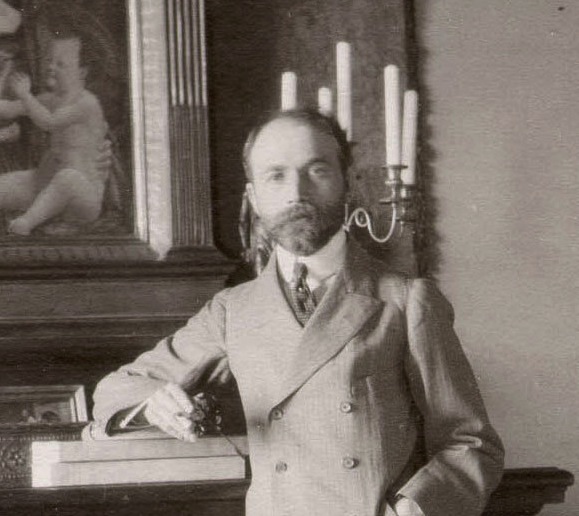

Berenson worked hard at being exceptional. Born Bernhard Valvrojenski in 1865, in a village on the outer fringe of the Russian Empire, he started out with nothing, went to Harvard, knew everyone, may have shared a mistress with J. Pierpont Morgan, inspired and infuriated people by the dozen, had no real profession or business yet lived better than a millionaire, hid out from the Nazis, taught several generations of leading professors and curators without ever being a professor or curator, reinvented himself multiple times, and, almost impossibly, survived well into his nineties.

It really began in Boston, where, in 1875, Berenson arrived with his Jewish-Lithuanian family. Though he lived almost all his long life in Europe, Berenson remained in some deep sense a Bostonian.

Rachel Cohen’s study, the first Berenson biography in a quarter century, tells all this and more with grace, economy, and deep sympathy for the numerous foibles of its subject. Not surprisingly, Cohen leans heavily on earlier biographers, Meryle Secrest and Ernest Samuels in particular, who had sorted through the massive archives before her. Cohen does make some mostly inconsequential errors (delft is not a type of porcelain, for example). The thrust of her psychological narrative is strong and convincing, though, and her writing is elegantly balanced and very readable. Non-specialists will find little off-putting shop talk here. There are plenty of vivid characters, many of them famous, and a plot line with satisfying twists and turns.

Part of Yale’s “Jewish Lives” series, the book pays dutiful attention to Berenson’s Jewish identity. Here, though, the narrative is relatively thin. Cohen describes Bernhard’s father, a tin peddler by trade, as an “Enlightenment Jew,” that is, non-practicing and inclined towards assimilation, and a frustrated intellectual. She suggests the family adopted the name Berenson to identify themselves with German-speaking families of Jewish origin, who were already well established in the United States (German “Bernhard” became “Bernard,” the French spelling, during World War I. Later, Berenson initiates used the shorthand “BB.”).

Berenson himself did not remain Jewish for very long. His second year at Harvard he converted to Christianity, baptized Episcopalian by the Boston Brahmin clergyman Phillips Brooks in Copley Square’s Trinity Church. Later, in Europe, he became a Catholic. Christian or not, Berenson was never particularly religious. These changes seem to be part of his lifelong habit of dropping parts of his identity that had become inconvenient. Even during World War II, when he was forced into hiding from Nazi invaders, Berenson was advocating assimilation and intermarriage “to the utmost feasible extent” as solutions to Jewish persecution.

If Berenson was self-invented he was not entirely self-made. Like a number of talented immigrant lads of exotic origins (Kahlil Gibran is another famous example) Berenson was taken up by wealthy Bostonians who supported his education and helped launch his career. They made it possible for Berenson to transfer, following a year at Boston University, to Harvard and, even after graduation, to travel and study freely in Europe for years without the burden of earning a living.

Exactly who these patrons were and what, if anything, they got in return for their support is somewhat of a mystery. Cohen suggests one or two names but only Berenson’s relationship to Isabella Stewart Gardner, which later evolved into a lucrative business association and aesthetic collaboration, is presented in any kind of focus. Berenson’s own family stayed poor and later survived on his remittances. We are left to believe that the young Bernhard got along, for over a decade, on little more than his charm and his wits.

At Harvard, Berenson both fit in and did not. In awe of the handsome, self-confident young Brahmins who filled his classes with the celebrated Charles Eliot Norton, the university’s first professor of art history, Berenson demonstrated a prodigious talent for foreign languages and got on well with at least some of his classmates. His associates included George Santayana, the future philosopher, and Charles Loeser, from a wealthy Jewish family in Brooklyn, who became an important art collector and, later, a rival.

Bernhard fell in with a literary crowd and became editor of the Harvard Monthly in his senior year. Clearly, Harvard’s late Victorian aura — old money, brains, Calvinist traditions, literary patina, tastefully posh surroundings, and elite social connections — became a model for his later career. Still, Norton’s wounding put-down to a colleague, “Berenson has more ambition than ability,” rankled to the very end of his life.

After graduation, Berenson sailed for Europe and, supported by his shadowy patrons, did not return for seven years. He spent much of his time trolling through museums and private art collections, socializing, and talking about art. With his genius for making useful connections, Berenson became known in wealthy collecting circles as some sort of “expert” on Italian Renaissance art. This tenuous status, even with no money or formal credentials attached, became the foundation of his fortunes.

His timing was perfect. A generation or two earlier, wealthy Americans collected prints, works by contemporary Americans like Church and Bierstadt, and French academic art. After the Grand Tour, they returned from Europe with a miscellany of antique furnishings and bric-a-brac, copies, reproductions, forgeries, pastiches, and a few original Old Masters, frequently misattributed. No one had any thought that famous masterpieces by the greatest European artists would ever be part of American collections. That was to change.

By the late nineteenth century, war, revolution, and a rapidly changing economy brought more and more superb works onto the European art market. There was nothing new about this. Ever since the Renaissance, the great collections of the European nobility had regularly changed hands and countries, often traded in bulk. The new element was American money.

Great paintings, writes Charles Hope, had always been “the supreme example of the sort of luxury items that royalty has almost always coveted — hugely admired, very hard to find, prohibitively expensive, and of no practical use.” Their appeal to status-conscious American collectors like Andrew Mellon, Samuel Kress, J.P. Morgan, Henry Clay Frick, and Isabella Stewart Gardner, was similar.

But the Americans had a problem. The field of art history barely existed; the market was still loaded up with the same sort of junk that smooth-talking Europeans had foisted on an earlier generation of Yankee tourists. The new American collectors didn’t want to be swindled or pay too much and, with good reason, they didn’t trust the dealers to make the attributions. They needed an expert who knew both the Europeans and the market inside and out but was somehow independent of both. Berenson fit the bill. At its peak, his reputation was such that he could convert, with a wave of his hand, dross into gold and back again.

Mrs. Gardner, whom Berenson knew from his Harvard years, possibly through Norton, was his first great client. For her, he located, at bargain prices, some of the most important European paintings ever owned by an American, masterpieces that later found their way into her private museum on Boston’s Fenway. This collection remains his greatest monument in the United States.

Eventually, Berenson was making the equivalent, in today’s money, of around a quarter million dollars a year off his association with Gardner. He and his companion (and later wife) Mary Costelloe, a distinguished connoisseur in her own right, stayed at the Ritz, hobnobbed with the elite, traveled the resorts and capitals of Europe, and gave lecture tours.

Berenson was also, Cohen reveals, cheating his Boston patron. Without either side knowing his arrangement with the other, Berenson charged a percentage commission on each sale to both Gardner and the European dealer handing the transaction. He also exaggerated the sale price, sometimes drastically, in order to increase his take. It was a daring, career-risking strategy to boost his earnings. Cohen says he was very nearly found out, more than once.

In later years, Berenson formed a lucrative, secret partnership with the flamboyant British art dealer Lord Joseph Duveen. Duveen’s outrageous marketing strategies, which eventually landed him in court, are the stuff of legend. All Duveen wanted from his partner, though, in return for his lavish payments, was to be able to whisper in his client’s ear “Berenson says…” But even this much drove Berenson to distraction.

Outwardly, Berenson now lived like a grandee with a fortune dating back to the Medici. He rented and later purchased an old Tuscan farm complex outside Florence. Originally in a primitive state, Berenson and his harried architects gradually transformed it into Villa I Tatti, a neo-Renaissance stage set where he worked on his books, kept his growing research library, and entertained a steady stream of luminaries and would-be disciples. When not traveling himself, he walked the elaborate gardens with visiting friends like Edith Wharton, frolicked with his many mistresses (one of whom later doubled as his librarian and general manager), and, as an increasingly ancient legend, accepted the homage of passing tourists like Ernest Hemingway and Lee Bouvier until he died in 1959. Then, despite years of resistance, Berenson’s alma mater accepted his bequest of the estate and its contents. Today, I Tatti is a residential research center for scholars of the Italian Renaissance.

Cohen, who teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence, devotes little space to Berenson’s art historical methodology, now largely superseded by modern approaches. She relates Berenson’s less admirable qualities without judging them. Her readers may not be so generous.

Plagued by the many demands and self-contradictions of his life and career, Berenson was often touchy and not easy to live with. He collected frenemies like George V collected stamps. The consummate host was a horrible mate. After stealing her away from her Irish husband, Berenson kept his relationship with Mary Costelloe covert enough to avoid denting his social standing. When, years later, Mary’s husband died, Berenson married her with studied reluctance, yet still refused to let her live with her beloved children. Perhaps fearing their competition for her attention, he wouldn’t let her have any more, either. When she became pregnant with a child he suspected was not his, he pressured her into having an abortion.

Bernard relied on Mary as his editor and collaborator, took credit for her work, and sent her enthusiastic letters about his numerous love affairs with other women (Mary herself had a penchant for beautiful, wispy young homosexuals). The excruciating pressures of managing Bernard’s life and running I Tatti, with its torrents of high maintenance short-term tenants and casual visitors, eventually drove Mary, exhausted, to an asylum. She never really recovered. Back at I Tatti, she was apparently happy to have another mistress move in and take on her many burdens. Berenson’s ability to mesmerize his women was clearly formidable.

It is sad that so little of Berenson’s legendary charm translates into print. He mesmerized his listeners when he talked about art but, to his constant chagrin, could not carry the effect into his writing. He was adored by generations of leading art historians — John Pope-Hennessy, Kenneth Clark, Agnes Mongan, Sydney Freedberg — but what exactly they learned at his feet is mostly lost to us. His indirect influence on American taste and American art museums, not just the Gardner, is immense. But today, most art-loving Americans recognize his name only dimly, if at all.

At the end of his long life, Berenson, caught helpless, he thought, between his intellectual yearnings and his constant need for money and social status, considered his life a failure. In Cohen’s book, though, he comes across as the embodiment of a certain kind of American dream: not the house, car, and kids most of us settle for but the ability to reinvent yourself at will, not just once but as often as necessary, rising free of race, family, country, religion, class, and, ultimately, even time itself.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

Tagged: Bernard Berenson, Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade, Rachel Cohen

hi,

how did berenson, son of poor jewish immigrants, get into harvard at all? how? precious few like him did.

and what was his “art historical methodology,” superseded as it has been?

In the nineteenth century, Harvard could and did admit anyone it wanted to admit. If you had the right connections, you were in. There were no SATs, no affirmative action programs, and demand was much lower than it is now.

Berenson adopted a system of attribution (he didn’t really invent it) using small details to identify the artist (shapes of hands, brushstrokes in landscapes, etc.). This is a bit like the methods handwriting analysts use to authenticate a signature. The method is still in use but it has been expanded with scientific materials analysis, X-ray and infrared photography, more sophisticated provenance research, and other techniques that Berenson did not use or did not have access to. He typically worked from black-and-white glossy photographs rather than the originals, which would be considered ridiculous today, and he did not take into consideration such things as restoration to the extent experts do today. The general assumption nowadays is that the scientific methods trump everything else though I am not sure this is always justified. The great connoisseurs still tend to act largely intuitively– i.e., they are able to read a painting the way others might read a face, but they often can’t explain how they actually process what they see.

As I say in the review, the Cohen biography does not say a whole lot about Berenson’s methods but other biographers, Secrest, for example, go into more detail and there are academic papers and dissertations that discuss it at length.

Hi,

How is it that Berenson survived the Nazi occupation of Italy? That is, due to his being both Jewish and American (an enemy alien)? Was it because of his many connections and favors he had done in the past for would-be powerful protectors (vis-a-vis his art work appraisals)? Thanks.