Poetry Review: Nobel Prizewinner Vicente Aleixandre—The Poetics of Kissing

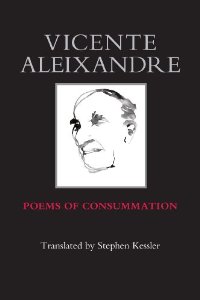

This translation of Poems of Consummation is important for several reasons, one of which is that the 1977 Nobel prizewinner—despite the award—has long been insufficiently preeminent in our Anglo-American view of twentieth-century Spanish poetry.

Poems of Consummation by Vicente Aleixandre. Translated by Stephen Kessler, Black Widow Press, 135 pp. $19.95.

By John Taylor.

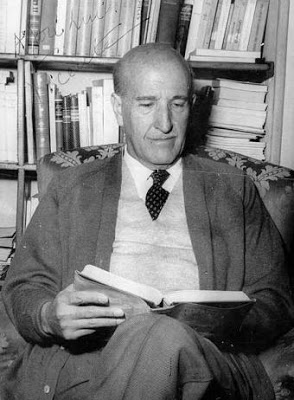

Faithfully and engagingly translated by Stephen Kessler, Poems of Consummation (1968) is one of the last books written by Vicente Aleixandre (1898–1984). It is an important translation for several reasons, one of which is that the 1977 Nobel prizewinner—despite the award—has long been insufficiently preeminent in our Anglo-American view of twentieth-century Spanish poetry. Aleixandre was a leading modernist in the “Generation of 1927,” an informal group comprising Rafael Alberti, Luis Cernuda (also expertly translated by Kessler), Federico García Lorca, Jorge Guillén, Pedro Salinas, and a few others. His poetry, however, at least in English translation (and in French translation as well, by the way), has remained in the shadow of Lorca’s (above all), as well as Alberti’s and perhaps even Guillén’s.

Is this because his verse is comparatively more difficult to translate than theirs? Or because his poetic oeuvre, without being entirely apolitical, is less political? Or because his evocations of love are philosophically more intricate and thus less immediately lyrical? These are hypotheses that the reader of this welcome version might wish to ponder. In any event, he will likely be won over to this “later, highly distinctive work of an extraordinary poet,” as Kessler rightly claims in his Prologue.

From the onset, Poems of Consummation is often touching because it devotes a special place to el beso, “the kiss,” and the 50 pieces gathered here give philosophical resonance to this simple amorous act. Consider the poem “Kisses are like the Ocean.” “What matters is an echo of what I heard and hear,” Aleixandre writes, adding

You were more substantial,

more lasting, not because you were kissed,

nor because kisses burned you more firmly into existence.

But because the ocean,

after its fearful rush on the sand, grows deeper.

In greens or in foamy whites the ocean happily retreats.

As it fled and returns, you never return.

[. . .]

I find only edges. Only the edge of a voice that’s left in me.

Your kisses like strands of seaweed.

Magic in the light, then they turn away, dead.

As in many other poems of this collection, kissing is no mere symbol of bodily sensation but also fosters broader themes involving the role in our lives of memory, the Other, Nature, death, presence, and absence.

This leitmotiv of the kiss goes back much earlier in Aleixandre’s work. The sometimes longish, yet mostly short and pithy poems of this absorbing late collection movingly sum up a vision of love already elaborated in his best known and more exalted work, Destruction or Love (1934), a selection of which Kessler rendered long ago for Green Horse Press (1976) and which has also been translated by Robert G. Mowry at Susquehanna University Press (2000). In Destruction or Love, Aleixandre notably asks (in Kessler’s version) a fundamental question around which revolve poems throughout his extensive oeuvre: “Why kiss your lips, knowing death is near, / knowing that loving is only forgetting life, / closing our eyes against the present darkness / to open them on the shining limits of a body?”

As should be clear, Aleixandre’s poetic use of the kiss is no romantic throwback to a kind of puritanical squeamishness about overt sexual allusions. On the contrary, the poet attributes a central role in human experience not only to the sense impressions garnered by a solitary individual but also to mutual sensuality. He wrote more suggestively erotic poems in other collections, a few examples of which are found in Shadow of Paradise, a volume available in Hugh A. Harter’s translation for the University of California Press (1993).

Still, lips meeting lips emerges as the most conspicuous imagery in Aleixandre’s verse and constantly plays a pivotal role. Kissing, and specifically the memory of kissing, provides the very impetus for his writing, which often attempts to comprehend what living consists of, feels like, means. Take a revealing short poem, “Posthumous Kiss,” from Poems of Consummation:

Quiet like this, my lips on yours,

I breathe you. It’s either a living dream or we’re alive.

The life we can sense is in the kiss

that lives on, alone. Without us, it shines.

We are its shadow. Because it is our bodies when we’re gone.

The key line is “the life we can sense is in the kiss.” What, after all, gives us the impression, let alone the certitude, that we are alive? One approach taken by poets ever since Antiquity has been to isolate a moment of heightened awareness and praise it as our surest sensation of life. Philosophers, in turn, have sought to describe what such moments signify and imply, usually by analyzing a self-reflexive cognitive phenomenon whereby we become conscious—suddenly, fleetingly—that we are experiencing a thought or a feeling. This kind of auto-perception, or “apperception” as Kant, Leibniz, and Maine de Biran termed it (in contrast to “perception”), can give us, sometimes disturbingly, a brief yet vigorous—and memorable—impression of aliveness, of life flowing through us.

In the context of Aleixandre’s poetry, this is where the Other comes in. A kiss is a multi-sensorial and, often, hyperconscious affectionate act jointly undertaken by two human beings. In contrast to many forms of sexual play and intercourse, where the ultimate goal is to lose oneself in sensation, to leave one’s self, as it were, in the ecstasy—ek-stasis, roughly “to put out of place, out of oneself”—of orgasm, kissing keeps one “in place” and attached, arguably with comparatively greater multi-sensorial complexity, both to the Other and to oneself. Lips meeting gently, joyously, spontaneously (for the first time) or passionately (for the umteenth time) can induce a rich and elaborate “apperception” in both participants. Each participant becomes much more acutely aware, than usual, not only of the Other’s presence but also of something seemingly partaking of the very essence of life. Standing or lying face to face with one’s beloved and kissing him or her is a highly conscious exchange that not only increases one’s individual experience of pleasure but also deepens one’s—and the Other’s—experience of aliveness. This is the premise upon which Aleixandre’s poetics of kissing is founded.

However, a nuance must be added. In the poem “Posthumous Kiss” quoted above, the poet evokes kissing and “breathing” the Other as resembling a state in which the poet is unsure whether he is experiencing a “living dream” or a present sensation. Moreover, he adds that the kiss “lives on, alone,” that “without us, it shines,” that “we are its shadow.” This memorability of kissing is crucial. “A man’s memory lives in his kisses,” Aleixandre declares in “Whoever Does, Lives,” for even if “to count one’s life by the kisses given / isn’t a happy thing[,] it’s even sadder to give them and not remember.” Rather like the poem “Kisses are like the Ocean,” cited at the beginning of this review, another piece, “It’s Raining,” juxtaposes rain, which is an image from the outside world and from the present, with the memory of a past kiss:

This afternoon it’s raining, and it pours

your image.

[. . .]

I don’t hear a thing. Memory gives me just your image.

Only your kiss or rain falls in what I remember.

It rains your voice, and rains your sad kiss,

your deep kiss,

your kiss drenched in rain. Your lips are wet.

Wet with memory our kisses are crying

out of a delicate gray

sky.

In other words, as we live from moment to moment, the present furnishes us with natural phenomena that both solicit and blend with our memories. And these memories soon become more powerful, more present than the phenomenon per se that is taking place in the present. The present is fleeting, but the presence of the memory, especially when the kiss is remembered in all its imposing sensorial and emotional detail, lasts comparatively longer. It follows, for Aleixandre, that life can be experienced—“re-experienced” is probably more appropriate—with increased awareness when the mind and the body are fully grasped by the presence of the past kiss. This kind of outlook resembles Saint Augustine’s concept of “the presence of things past.”

According to Kessler, Aleixandre “reveals how memory, elusive and ineffable as it is, remains the strongest evidence we have of having lived—especially as we face life’s end—and the combination of longing and possession it engenders is an unsatisfactory yet also consoling recovery of the lover’s lost embrace.” He specifies:

The mouth and the lips especially, the kiss and the speaking voice, are the means through which we register our richest grasp of life. At the far edge of existence, in the face of death, the remembered kiss and the poet’s voice (condemned to mere paper but still singing) redeem what’s left of us, even if it is a diminished incarnation of the beauty and vitality of youth.

Are Aleixandre’s poetics of kissing nonetheless based on a questionable optimism? Is it really conceivable, as sometimes almost seems to be implied, that a sensation or an emotion lingers after physical death, an analogy to which might be the Christian concept of the survival of the soul? This is to say, has Aleixandre substituted for the Christian soul the notion of an amorous sensation—the kiss—that survives the annihilation of death? In a sense, he has in fact done so, yet only if memory, which is also ultimately perishable, is taken into account.

For destruction and death are equally present in these poems, and this is what gives Aleixandre’s Poems of Consummation, and his oeuvre in general, such subtle dialectical interplay. In an important short poem, “Present, Later,” he writes

Enough. There’s no kiss after life, but I can feel you.

Your finished lips hinted

that I’m alive. Or I’m the one calling you.

To place my lips on the idea of you is to feel you

as a proclamation. o yes, you exist, terribly.

I’m the finished one, who spoke your name, like a rite,

while I was dying.

Born of me;

here because I said you.

French poets like Yves Bonnefoy, Philippe Jaccottet, and Pierre-Albert Jourdan have insisted upon the finitude of human existence, all the while seeking to intuit something beyond the threshold of mere physical materialism. Necessarily, their quest must stop on this threshold—which is often what their poems or poetic prose texts are all about. The poetry and poetic prose of these French poets are often set in Nature (though Bonnefoy has also dealt with the theme of love) and attempt to pinpoint the conditions that might enable one to discover, or recover, some kind of hope despite the overwhelming definitive quality of death.

Aleixandre rather similarly gropes for conditions of hope, yet most often while facing another human being in the present or, now that he has reached old age, in his memories. In the poem above, as in many others in this stimulating gathering, his beloved—it is not specified whether it is a man or a woman—remains alive through his memory of kissing him or her. And indeed, now long after the poet’s death, the inscribed memory that is the poem we are reading also passes on a kind of hope. By its very poetics, it helps us, in turn, to keep on living, to search for hopes that can motivate our own desire to live, and to relish in our very aliveness.

John Taylor has translated many French poets, most recently Jacques Dupin (Of Flies and Monkeys), Philippe Jaccottet (And, Nonetheless), Pierre-Albert Jourdan (The Straw Sandals), and Louis Calaferte (The Violet Blood of the Amethyst). He is the author of the three-volume essay collection, Paths to Contemporary French Literature, as well as Into the Heart of European Poetry. He has written eight books of poetry and short prose, including The Apocalypse Tapestries, Now the Summer Came to Pass, and If Night is Falling. He lives in France.

Tagged: Black Widow Press, Poems of Consummation, Spanish poetry, Stephen Kessler

An excellent,evocative article John.I’ve always loved the poetry of Lorca, I can’t wait to read Aleixandre’s poetry in both languages.Thank you