Jazz Review: At MIT, Jazz Musician Don Byron Does Gospel Right

Jazz musician Don Byron is nothing if not eclectic, but his own playing is always penetrating, challenging, energizing, and his compositions vehicles for both intense exploration and tenderness.

Don Byron’s New Gospel Quintet with Don Byron (clarinets, saxophones), Carla Cook (vocals), Nat Adderley Jr. (piano), Jerome Harris (bass guitar), Pheeroan akLaff (drums). With the Boston Arts Academy Spirituals Ensemble. At Kresge Auditorium, MIT, Cambridge, MA, October 27.

By Michael Ullman

Don Byron was first seen by this Bostonian playing a wildly ecstatic clarinet, his accents sticking out like straw in a haystack, in the New England Conservatory’s Klezmer band. The dread-locked, young man, an African-American from Brooklyn who in the age of saxophones decided to focus on the clarinet, was already crossing boundaries. Since then, he has recorded the often parodic music of Mickey Katz (including his “Haim Aften Range”), a tribute to Raymond Scott (who wrote music for Bugs Bunny cartoons), Lester Young (“Ivey-Divey”), as well as several stirring tributes to the history and culture of black folk. That’s not the extent of his interests: I once drove through a snowstorm to his house in western Massachusetts for an interview in which he talked mainly about Henry Mancini. I narrowly avoided watching Peter Gunn reruns. Byron seems to admire the wildness of some music—klezmer and blues saxophonist Junior Walker for instance—and the tightly controlled, as in Scott and Mancini. He loves opera, the Bach B Minor Mass, and the blues saxophone of Junior Walker.

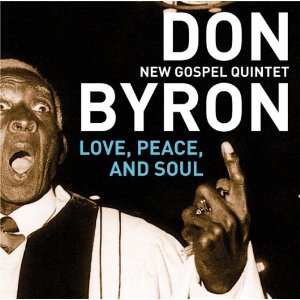

He’s eclectic, but his own playing is always penetrating, challenging, energizing, and his compositions vehicles for both intense exploration and tenderness. At Kresge Auditorium on Saturday night, Byron told us of his newly deepened interest in spiritual things and in black gospel music that led to his most recent disc, Love, Peace and Soul (Savoy Jazz). His band of state-of-the-art jazz players—Xavier Davis on piano, Jerome Harris on electric bass, and Pheeroan akLaff on drums—played behind gospel singer Carla Cook. They centered on the music of the “father of gospel music,” Thomas A. Dorsey, but also performed a number by Dorsey’s hero, Charles Tindley, some contemporary gospel and, modestly enough, only one Byron piece, his “Hmmm.” Thomas A. Dorsey was the key.

It was Dorsey, who in the 20s was known as the blues singer Georgia Tom, who against some serious opposition brought the blues sound, its weight, including its moans and fervor, into black sacred music. He wanted sacred music to evoke the excitement of the blues. Accompanying Ma Rainey, Dorsey once saw “some woman scream out with a shrill cry of agony as the blues recall(ed) sorrow because some man trifled on her.” He was still a blues man. A turning point (he had several) came when at a Baptist convention he heard the Reverend W. M. Nix sing a spiritual with all the turns, moans, and embellishments of the blues and in a virtuoso style few blues singers would have attempted. He decided to turn from ribald blues (he had composed “It’s Tight Like That”) to write “songs of hope and faith,” and he found he could teach singers “how to say their words in a way, in a mournful way and more of a crying way, more to show the sadness and the weight that was upon them, the burden.” Eventually he would tutor such gospel greats as Mahalia Jackson in this blues-driven, virtuosic style.

It was that melancholic burden that led Dorsey to write his most famous song, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” which Byron played after his band warmed up with Eddie Harris’s “Sham Time.” Byron told a foreshortened version of the story Dorsey himself tells on Precious Lord: Recordings of the Great Gospel Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey (Columbia Records), an indispensable disc for lovers of gospel. Having left his pregnant wife, Dorsey was on the road at a revival in St. Louis in the early 30s when he received a telegram that his wife had died in childbirth. The infant died soon afterward, and Dorsey went into a depression. He emerged when his friends took him to the basement of a college, where he fooled around at the piano and was suddenly inspired. The words came to him, he said, like drops of rain: “Precious Lord, take my hand, lead me on, let me stand . . . Lead me on to the light.”

At Kresge, and on disc, Byron introduced the Dorsey hymn with an unaccompanied tenor solo in his typically dramatized indirect style. There’s a danger, of course, in juxtaposing post-bop jazz with something like folk music. It can seem as if recherché notes are being spilled like sour milk over a song’s innocent harmonies. Remarkably, this never seemed true in Byron’s renditions: his singer, the estimable Cook, provided a solid gravitas that posed a compelling counterweight to Byron’s phrases. The result was not an act of contraction, an expansion of the sound of gospel, much as an Eric Dolphy stretched the sound of bebop.

Don Byron and the other members of the quintet at Kresge Auditorium, MIT. Photo: Christine Southworth

Byron typically didn’t answer Cook’s phrases, as a blues guitarist might: rather, he played counter-lines along with her. He peformed Dorsey’s ‘It’s My Desire” on the usually shrill sounding Eb clarinet: here his intro led to a rocking first chorus, brought down to earth by the quietly elaborate solo of pianist Xavier Davis, a star throughout the night. Byron got the crowd clapping and the house moving on “Walking on the King’s Highway,” but for this listener it was the quietest moments that were the most stirring, such as when bassist Jerome Harris and Cook, for instance, began the Charles Tindley hymn, “Beams of Heaven,” made famous by Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Cook singing over the gentle back beat on hi-hat provided by akLaff.

The concert ended after Byron brought out the Boston Arts Academy Spirituals Ensemble, a choir of high school students who accompanied him skillfully on contemporary gospel composer Kirk Franklin’s “Hosanna.” “My God,” Byron said, “knows some fancy harmony.” On this number, and on Franklin’s “I Smile,” they may have taught the Deity a thing or two. The performance didn’t sound like the blues anymore but rather as if the burden of life had indeed been lifted, if only for a time . . .

Tagged: Boston Arts Academy Spirituals Ensemble, Don Byron, Don Byron’s New Gospel Quintet, Love