Book Review: “The Barcelona Brothers” — A Nasty Piece of Spanish Noir

International noir novels no longer revolve around exotic police procedurals or gimmicky detective stories. They aim to pound readers into the pavement.

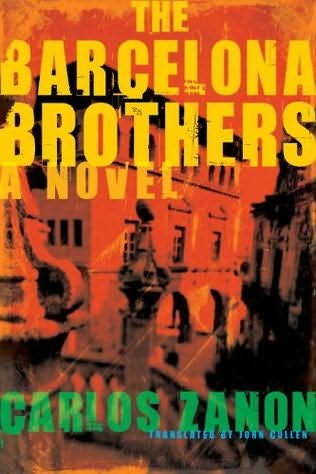

The Barcelona Brothers by Carlos Zanón. Translated from the Spanish by John Cullen. Other Press, 289 pages, $15.95.

By Jim Kates.

A Catalán, a Moroccan, and a Pakistani walk into a bar in Barcelona. . . .

This could be the start of a joke set in the new, multicultural Europe, something that might erupt into a raucous comedy of diversity, generating the kind of verve and effervescence of the Paris found in Daniel Pennac’s Belleville Quartet. Instead it’s the beginning of a very nasty little novel, The Barcelona Brothers, by Carlos Zanón, newly translated into English by John Cullen. But perhaps I should not be so surprised by Zanón’s determination to be grim.

Suddenly it seems noir has busted out all over. What once appeared to be the smoggy climate of southern California, windy Chicago, and just all-round grimy New York now overhangs Tokyo and Stockholm, Bangkok—and Barcelona. Maybe it’s just the globalization of everything, maybe it’s the success of Akashic Publishers’ noir short-story series; but we’re no longer following exotic police procedurals or gimmicky detective stories. We’re being pounded into the pavement:

The barrio’s been fed up for some time. The young people are bored. Whites, yellows, and blacks. On this point they’re in agreement, while the older folks don’t forget that, in one way or another, they were swindled, too. Tolerance, cultural diversity, and intermarriage are pieces of slogans suited to newspaper editorials no one in the barrio reads, songs no one listens to, speeches spewed out by politicians for whom many in the audience can’t even vote. And the people live, love, hate and bear up as best they can. Some wear headscraves, others play their radios too loud, and the rest nostalgically remember the city when she was a broad-hipped matron, venerable and distinguished, who knew how to keep her sweepings under rugs and in jail cells.

There’s something naïve about this description, buried as it is halfway through the book, as if the third-person narrator had suddenly looked around the mean streets of his own story, discovered that down them there was walking no man who was not himself mean, and needed to explain that absence. Unredeemed by any artistic purpose or social significance, it makes for glum reading:

With difficulty, Rocío Baeza rises to her feet. She hasn’t the vaguest idea where she is. She walks around awkwardly for a good while, looking but not recognizing any of the buildings that surround the open ground where they’ve left her. . . . She understands that she’s hours away from her house, that the dawn is breaking, that her daughter’s jacket is ripped to tatters and stained with blood. She looks at the van as it pulls away and fears that they’ll return and run over her. But they don’t do that.

And that’s only what happened after Baeza, a bit player in the story, has been kidnapped and raped.

The main plot begins with the bludgeoning to death of a particularly unsavory thug and plods on from there. Zanón gives us the unremitting internal life of a number of characters, but their internal life itself is so poverty-stricken, so limited, that’s hard to see the point, or to want to follow them to the grim ending, an unsuccessful suicide attempt. The brightest of the whole bunch, Alex Dalmau , has little idea what’s going on either inside or around him.

Alex tells himself, without conviction, that he’s done more for Epi than Epi would ever have done for him. But he, Alex, made a promise. To Mama. He swore an oath to her. So let’s recapitulate: He’s done everything he could.

The others are as clueless as his brother Epi’s van, with a broken ignition key, careering downhill until it coasts to an abandoned stop on level ground.

The gimmick of the Akashic noir series set in different cities is that, among the various quality of the stories themselves, we get a gritty sense of each individual city, its underground particularity. Brooklyn Noir gave us presumably authentic Brooklyn, St. Petersburg Noir tried for authentic St. Petersburg. Barcelona Brothers, from its very title, promises us the same intimacy. Alas, the story could be grinding on anywhere, the city undifferentiated from any other European backstreets. (At least they speak Catalán from time to time, unlike the protagonists in Woody Allen’s film Vicky Cristina Barcelona.) The climactic action takes place on Granada, a street east of the Old City, in a barrio tourists are wisely discouraged from frequenting. Instead of being given flavor of the neighborhood, we are quickly propelled into a characterless, empty apartment.

Readers should be equally discouraged from The Barcelona Brothers.

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Muddy River (Carcanet), a translation of verse by Russian existentialist Sergey Stratanovsky. His translation of Mikhail Yeryomin: Selected Poems 1957-2009 (White Pine Press) won the second Cliff Becker Prize in Translation

Tagged: Carlos Zanón, John Cullen, noir, Other Press, Spanish-literature