Book Review: “Emmaus” — A Fictional Puzzle Wrapped in a Spiritual Enigma

Alessandro Baricco’s novella Silk, filled with inchoate erotic longings for which there is no explanation, became an international bestseller. Emmaus, his latest book in translation, also contains mysteries.

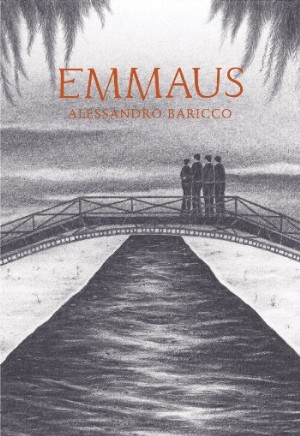

Emmaus by Alessandro Baricco. Translated from the Italian by Ann Goldstein. McSweeney’s Books, 144 pages, $22.

By David Mehegan

Alessandro Baricco is an Italian director, music critic, novelist, and founder of a creative writing school in Turin called Scuola Holden—named for the character Holden Caulfield in J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Emmaus, originally published in 2009, is the fifth of his eight novels to be published in English. His 1996 novel Silk, an international bestseller, was made into a much-derided 2007 film directed by Francois Girard and starring Michael Pitt, Keira Knightley, and Alfred Molina.

Silk is the story of a French trader in the 1860s who travels to Japan to buy silkworm eggs. While there he becomes obsessed with his egg supplier’s concubine—of whom he catches only a glimpse—and returns to the country repeatedly in hopes of a direct encounter. In structure the novella—it is only 91 pages—consists of 65 short vignettes written in an oddly cryptic style. Since none of the mysteries are resolved, the novel seems to be mostly about inchoate erotic longings for which there is no explanation or answer. That indeed was the chief complaint of film reviewers.

Emmaus has some of that same tone. Set in the present, it concerns four teenage, male friends in an Italian city. The story is told in the present tense by an unnamed narrator, one of the four (yet the voice is clearly not that of a teen but a sophisticated adult). The other three are Luca, Bobby, and the Saint; the latter two are nicknames. The boys are believing Catholics from pious families who in their free time volunteer to care for the elderly sick in a hospital. They have a band. They are also fixed, the narrator explains with care, firmly in the most conventional middle class and feel wholly divided from the daring affluent society of Andre, a girl with whom all four are fascinated.

Luca and the narrator are the least clear of the quartet. The Saint is a religious fanatic who entreats Andre’s mother to attend to her daughter’s immortal soul by sending her to church and Confession. Bobby (he is called that because his older brother looks like John F. Kennedy) is a sensible realist who verbally attacks the Saint for playing the part of a moralizing demi-priest.

Andre is impulsive, a bit wild, and seriously depressed. She had attempted suicide sometime in the past, and the boys understand that though she survived, by the decisive act itself she had in effect already died in the sense of no longer caring about life. They observe her amorous adventures from afar. Separately and as a group, their fates eventually become intertwined with hers with explosive repercussions on their lives and respective relationships.

One must say that, as in Silk, there is not much to this story in terms of plot, and the eventual violent events come out of the blue and are never explained in terms consistent with what we have been led to believe of the characters involved. Like that of Hervé Joncour, the silkworm trader, the complex weave of their longing and mystification about themselves, Andre, and one another has for the reader more the texture of burlap than silk.

But it might be that plot is beside the point of Emmaus, that we are not supposed to understand Andre, Luca, Bobby, the narrator, or the Saint. The underlying theme seems to be the hopeless impossibility of an abstract moral/religious system—in this case orthodox Catholicism—coming to grips with the drives, forces, and deeds of real life. Although the narrator says, “we believe in the God of the Gospels,” it is clear that the boys lack any pity or authentic interest in the helpless people whose sheets and urine bags they change; they do it because that is what the rule of Christian charity requires. And their piety is no impediment to experimental sex with their girlfriends or lust after Andre.

The title of the novel is taken from the story in the Gospel of Luke (24: 13-35) in which two disciples are traveling on a road to the village of Emmaus shortly after the crucifixion of Jesus. A stranger takes up with them, at first seeming not to know what has happened in Jerusalem. When they inform him, he begins to explain to them why Jesus had to suffer in light of the prophecies of Scripture. They sit down to lunch at an inn, the stranger breaks the bread, they instantly recognize him as Jesus, and he vanishes.

The boys love this tale, says the narrator, because “in the whole story, no one knows. At the beginning Jesus himself seems not to know about himself, and his death. Then the men don’t know about him, and his resurrection. . . . Small hearts—we nourish them on grand illusions, and at the end of the process we walk like the disciples in Emmaus, blind, alongside friends and lovers we don’t recognize—trusting in a God who no longer knows about himself. For this reason we are acquainted with the beginning of things and later we experience their end, but we always miss their heart.”

Toward the end of the novel, such intellectual/philosophical ruminations become increasingly dense and obscure, so that we not only do not understand exactly what has happened or why, but we understand through a glass darkly, if at all, what the narrator is trying to say about it:

“We have made a fetish of a logical contradiction—we are the only ones who worship a dead god. And then how could we not learn, above all, this capacity for the impossible—and the ambition to close any gap? So, while they were teaching us the straight way, we were always spider webs of paths, and everywhere was our goal.”

If this means that life is more complicated than allowed for in formal moral and philosophical systems, we say right, OK. Got that. But this is a novel. What about Andre, Luca, and the Saint? If they are meant to be figures for the Gospel evangelists (one is named Luke, after all), the parallel is hard to make out. Outside the world of Agatha Christie, not every act and motivation in fiction need be, or even should be, fully clarified. But in an odd way, this work has much of the very essence of Christian belief that it disputes: the idea that the mystery of it all, allied with acceptance of narrative assertion, is all the fact we should need.

On May 31th, Alessandro Baricco will be in Boston, at the Dante Alighieri Society, co-organized by the Consulate and the association of Italian Professionals in Boston.

David Mehegan can be reached at dmehegan@gmail.bu.edu.

Tagged: Alessandro Baricco, Ann Goldstein, Emmaus, italian-literature

My feeling about this book and your review is that this is a story that is not really a novel–it’s more of a long prose poem or a contemplation on a psychological phenomenon. It has one central theme–we do not recognize the significance of many things around us, including the human relationships, the suffering of others, our own suffering, etc until it’s already occurred and been represented to us in some form of narrative explanation. But–and this is key–the emotional impact of understanding that relevance is highly dependent on it first having gone unnoticed. The human mind loves a re-disovery but almost always misses the first encounter because it has no frame of reference.

Beautifully said, Helen