Book Review: “Behind the Beautiful Forevers”

The people of Annawadi live in conditions so bleak that Behind the Beautiful Forevers evoked, for one Indian reviewer, Primo Levi’s depiction of life in concentration camps.

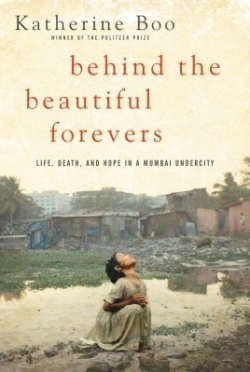

Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo. Random House, 256 pages, $35.

In the past decade, foreign bureaus of one major news organization after another have been eliminated or down-sized. There’s no money for this kind of journalism anymore. Most media institutions no longer employ foreign correspondents and rely on the wire services for news from abroad. We rarely get to read in-depth, international reporting unless it’s from a war correspondent embedded with troops. Most of the time, it’s soundbites or dispatches from correspondents rotated into trouble spots who rely on interpreters and a longtime Casablanca-style cast of “usual sources” in place of “usual suspects” to supply and, sometimes, manipulate the news.

Katherine Boo’s first book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, is a rare exception to this contemporary rule. As much an ethnographer as a reporter, Boo began her career as a writer and editor in D.C. where she covered American poverty and the poor at three Washington publications including the Washington Post before joining the New Yorker in 2003. She’s committed to the long-form reporting that takes lots of time and immersion. Following in the footsteps of New Yorker international reporter Jane Kramer, whose Unsettling Europe remains one of my favorite books, Boo is less interested in profiling the leaders making major policy decisions and more in those who live out their consequences. When the American-born writer of Swedish descent married political historian and Indian national Sunil Khilnani a decade ago and began visiting India, he advised her not to take his country “at face value.” Clearly, she didn’t.

Her writing about poor populations in the United States had garnered several awards by the time Boo extended her examination of the poor in the world’s oldest democracy to the poor in its largest one (“an increasingly affluent and powerful nation that still housed one-third of the poverty and one quarter of the hunger on the planet”). Her title, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, comes from a local wall advertisement for Italian tiles in Annawadi, an Indian slum. Most of its inhabitants live in 300 makeshift huts. The poorest of the 3,000 squatters sleep outside on the bare ground. Her content draws on three years of visiting and reporting from this overcrowded and vermin-infested settlement, situated beside a noxious lake of garbage and sewage on land belonging to the Airports Authority of India.

In some ways, Boo writes traditional, fly-on-the-wall journalism, keeping herself and her opinions out of the story. She doesn’t speak the local languages and doesn’t herself live in Annawadi. But she has found ingenious ways of supplementing traditional journalistic practices—observation, repeated interviews, archival research—by lending her photographic and recording equipment to some of the slum kids and letting them document what they find important to their lives. Then, with the help of interpreters, she interviews and re-interviews them to reconstruct their experiences. Ingenious technique, I think, befitting the winner of a MacArthur “Genius” Award!

The result is an unusually intimate and detailed portrait of a place and its people, a colorful cast of Muslims and Hindus. The adult slum-dwellers—if they’re lucky—eke out an existence by menial forms of labor or scamming government programs directed at the poor. Their children often earn more than their parents by scavenging, recycling, and stealing from Mumbai’s international airport and its luxury hotels.

One of them, Abdul Hakim Husain, the teenage garbage-sorter, is the quirky character who drives the book’s narrative. The first chapter opens with him fleeing the police because he and his ailing father Karam Husain have been falsely accused of setting their one-legged, female neighbor on fire. Abdul is the financial mainstay of his large Muslim family, and telling his evolving story allows Boo to supplement her firsthand observations of daily life in Annawadi with insights into India’s criminal justice and political systems, its many layers of attempts at reform and countervailing corruption, its enduring caste system, and its endless stream of rural migrants, among many other themes.

The women of Annawadi are as interesting characters as the men. We meet Abdul’s mother Zehrunisa and the one-legged neighbor Fatima but, most memorably, the mother-daughter dyad Asha (“woman-to-see”) Waghekar and her studious daughter Manju. An ambitious, ruthless, and all but illiterate rural immigrant with an alcoholic husband, Asha is training to become an Indian version of Tammany Hall political boss Carmine DeSapio but behaves like stage mother Rose in Gypsy. Her daughter Manju is one of the slum’s hopes for the future, a girl who studies Shakespeare and Virginia Woolf, keeps the home fires burning, and teaches Annawadi children scraps of what she learns in whatever time she has left.

The people of Annawadi live in conditions so bleak that Behind the Beautiful Forevers evoked, for one Indian reviewer, Primo Levi’s depiction of life in concentration camps. Boo does not flinch from describing the extreme living conditions where people drop dead of starvation or untreated illnesses, and rat bites are a normal nocturnal phenomenon. She is also tough enough to describe the individuals and interpersonal dynamics that play out in this soul-crushing place without revealing her own opinions or reactions, until the very last chapter.

In the candid and rewarding Author’s Note that ends the book, Boo steps out of anonymity and tells us a bit about how she came to write it. In discussing her fact-checking methodology and her perception of Annawadian reluctance to dwell on unhappy episodes, she recounts an episode when her protagonist, Abdul, loses patience with her and the entire project:

“Are you dim-witted, Katherine?” he asked her when she asks him to repeat a sequence of unhappy events. “I told you already three times and you put it in your computer. I have forgotten it now. I want it to stay forgotten. So will you please not ask me again?”

This is a beautifully observed and beautifully written book about a place and its people that is not easily forgotten. I look forward to reading more of Boo’s work.

Helen Epstein is a veteran journalist and author of narrative nonfiction, now publishing ebooks at Plunkett Lake Press.

Tagged: Annawadi, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Culture Vulture, India, international reporting, Katherine Boo, narrative non-fiction