Jazz Feature: Exploring the Spirit of John Coltrane’s Music, On the Page and the Concert Stage

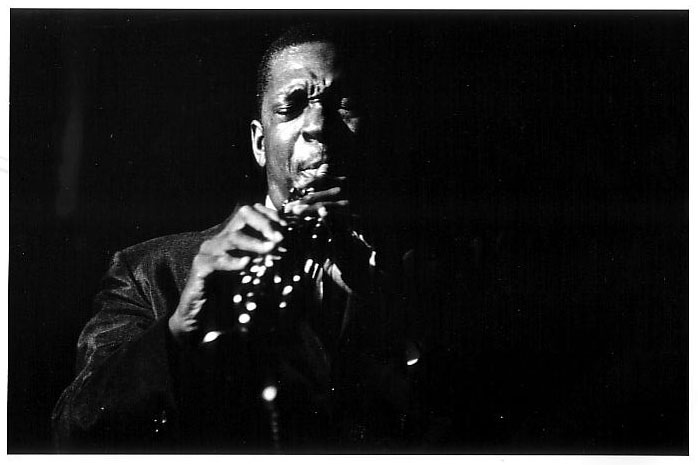

Anthony Wallace’s interview on last year’s John Coltrane Memorial Concert, which includes questions about a book on the musician’s spirituality, offers plenty to think about before the 2012 version of the homage to the master musician, which takes place on November 3rd.

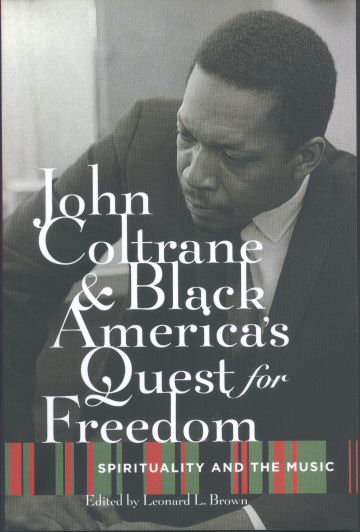

John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom: Spirituality and the Music, edited by Leonard L. Brown, Associate Professor of African American Studies and Music at Northeastern University, Oxford University Press, 256 pages, $27.95.

JCMC (John Coltrane Memorial Concert), Blackman Theatre, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, November 3 @ 7:30 p.m. Featuring 2012 Grammy-Award winning jazz drummer and composer Terri Lyne Carrington. Honoring Steve Schwartz, jazz producer and radio personality and Andy McGhee, master saxophonist and educator. Hosted by Eric Jackson.

by Anthony Wallace

This summer I had the pleasure of reading John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom: Spirituality and the Music. I’ve been listening to Coltrane’s music pretty steadily since the mid-seventies, and I was interested in reading what critics and scholars had to say about my favorite jazz musician and composer. Indeed, “Saint Coltrane” is how I’ve always privately thought of John Coltrane, and it was one of the many delights in reading the book to discover not only that this is a term I didn’t invent, but that there is a church in San Francisco based on that very idea: The Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church. “The inspiration came after the young couple had seen John Coltrane perform live in San Francisco in the year 1965. Being raised in the Pentecostal Church, Franzo King knew the presence of the Lord when it came through the power of the Holy Ghost. Seeing John Coltrane and hearing his sound that night was that familiar feeling he knew since childhood. It was the presence of God.”

This summer I had the pleasure of reading John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom: Spirituality and the Music. I’ve been listening to Coltrane’s music pretty steadily since the mid-seventies, and I was interested in reading what critics and scholars had to say about my favorite jazz musician and composer. Indeed, “Saint Coltrane” is how I’ve always privately thought of John Coltrane, and it was one of the many delights in reading the book to discover not only that this is a term I didn’t invent, but that there is a church in San Francisco based on that very idea: The Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church. “The inspiration came after the young couple had seen John Coltrane perform live in San Francisco in the year 1965. Being raised in the Pentecostal Church, Franzo King knew the presence of the Lord when it came through the power of the Holy Ghost. Seeing John Coltrane and hearing his sound that night was that familiar feeling he knew since childhood. It was the presence of God.”

The collection of essays Professor Brown has brought together identifies four stages in Coltrane’s musical development and focuses mainly on his final stage of Free Jazz and its connection to Coltrane’s search for spirituality–including the influence of the African American Pentecostal churches and the fact that Coltrane grew up with ministers on both sides of his family. The premise of the book, which we see in the title, is that this was a search for spiritual freedom on the one hand and political freedom on the other–not just for Coltrane himself but for all of Black America. It’s the search for spiritual transcendence that has drawn me to Coltrane’s music over the years, and the idea of that search having a political counterpart had never occurred to me but made perfect sense once I read about it. One of my interests as a teacher and writer has been the influence of Walt Whitman on 20th Century American Modernist poetry. In fact, last year I reviewed C. K. Williams’ On Whitman for The Arts Fuse. Reading Professor Brown’s book caused me to think about Coltrane in terms of Whitman and 20th Century Modernism, and one idea I came away with is that Coltrane was certainly a Whitmanian Modernist in that he saw a function for art that was simultaneously political and spiritual. A closer look at some of the ideas in Professor Brown’s book in terms of Langston Hughes would, I think, lead us back to Whitman, who would lead us to Emerson and Transcendentalism.

The book does a great job of exploring Coltrane’s music in terms of larger trends and patterns in African American music and culture, going all the way back to the Negro Spiritual, work songs, blues, field hollers, and how that music in turn takes Coltrane (and us) back to West African music. A parallel conversation about Coltrane as part of larger trends and patterns in American art, especially 20th Century Modernism, is also suggested. There is explicit reference to “Afro Modernism,” which took from the larger developments of American Modernism and added distinctly African American elements, for distinctly African American reasons, and it’s pretty clear (at least to me) that Coltrane was a mid-century genius of Modernism who masterfully synthesized the most important elements in both interconnected lines of descent: an African American tradition that stretches back to West African music but also an American and Western tradition that stretches back to Emerson and from there to the English Romantics, especially Blake. I now can’t listen to “Ascension” without thinking of Emerson and Blake.

These are some of the thoughts that occurred to me while reading the book, and the kind of larger context for listening to Coltrane that the book creates and which is clearly valuable. I asked Professor Brown about these and other issues regarding Coltrane at the approach of the 34th Annual John Coltrane Memorial Concert, which takes place Saturday, October 22 at the Blackman Theatre, Northeastern University, Boston.

Interview with Leonard L. Brown

Arts Fuse: This summer I had the pleasure of reading John Coltrane & Black America’s Quest for Freedom: Spirituality and the Music. The authors seem mostly to be academics, although you don’t list their credentials or indicate if the essays had been published as journal articles. Did you have a particular audience in mind at the start of the project?

Leonard Brown: None of the essays had been published before. Be clear that Anderson, Lateef, Wilson, Taylor, Washington, Price, A. Brown, Kernodle and I are active as performing musicians and scholars, now as well as during the period of creating the book. The one exception in this list is Dr. Taylor, who passed December of 2010.

Initially, I selected a core group of four along with myself in the same way I select musicians to play with me. I knew what I wanted to present about John, Black American culture, music and spirituality. So I reached out to those close friends and colleagues I knew “KNEW” what I wanted to create – aka the repertoire – and could “play it” with genuineness and sincerity in any key and at any tempo. In addition, each would bring his/her own unique voice and interpretations to the endeavor. I also knew there would be no question of integrity, because we all really knew the topics and we all have significant things to say about them. The initial group was Tommy Lee Lott, Herman Gray, Anthony Brown, Emmett G. Price III and myself. Maestro Anderson was also in from the start and was very supportive and encouraging. From there, we had planning meetings where we expanded on my initial concept. These meetings led to the collective decision to bring in other writers who we felt were worthy and would have significant things to say. The inclusion of interviews with masters Wilson, Taylor, Lateef and Russell was a decision I made later as the project expanded. T.J. Anderson provided the entrance into the work with the elegance and grace of the great Maestro and champion of Black music that he is.

AF: Were the essays solicited based on themes you wanted to explore, especially emphasizing the late or final period of Coltrane’s music and the intertwining themes of freedom and spirituality?

LB: The common themes that link all the essays, which is clearly laid out in the preface to the book, are freedom, sound, music and spirituality. Each writer had to submit an overview of their proposed essay to me and I then provided comments and where necessary, some guidance. I also read and, where necessary, edited essays.

AF: To what extent did you see a need for a book of this kind? How important is the scholarly conversation to the experience of listening to Coltrane? To what extent should the listener know the tradition Coltrane was operating within in order to really know and appreciate his music?

LB: I believe the book is essential to providing an insider’s view on Coltrane and the culture from which the music, he and us comes, and that that view or in this case, those views are critical to gaining a true knowledge and understanding what the music is about. Too often, aspects of African American culture are subjected to perspectives, paradigms, and frameworks that are inappropriate or improper. I firmly believe that one of the most important responsibilities of Black academic is to honestly and accurately educate about what our culture is. Music is central to our experience as a people – it is what makes us be who we are..

As for scholarly conversations, that is also what we do. Black folks have always had to be multifunctional in the Americas. We are Black folks first, then scholars and/or musicians and our views are important, significant and insightful. I certainly believe the scholarly conversation is important, BUT know that nothing is more important than the music that John played. If he had not played it so wonderfully and incredibly, we would have nothing to write about

AF: The essays in your book focus most heavily on Coltrane’s final period of musical development and his movement into Free Jazz. Is there one period of Coltrane’s artistic development that the current body of criticism has focused mostly heavily on?

LB: I don’t think so.

AF: A few writers in your book make the important point that free jazz was embraced by white listeners and critics but was not really embraced within the Black community. It is also a key point in the book that “jazz” is an African American art form that came out of African American culture, and that the two things should not be separated, or discussed in a way that separates them–I hope I’m paraphrasing accurately. Would you speak to the idea of jazz as intimately related to Black culture, and the extent to which you think it still is?

LB: Well, jazz was and is certainly embraced by humans of all colors around the globe and its roots are certainly in African American culture of the USA. Remember for most of its existence, jazz has been a dance music and not a so-called art form. It was functional in the daily lives of folks, encouraging them to have a good time, in spite of. Only in the last fifty years has the music moved into performance contexts where dance is eliminated and the musicians are looked at as artists. For a long time, jazz was an expression of Black life, which historically in the USA required one to use improvisation just to survive. Over time, much of this has changed and since desegregation, the subsequent demise of many black communities has often resulted in a disconnect between jazz music, musicians and black life, with New Orleans being an exception.

As for critics, one must really pay attention to who embraced what and when. The music called jazz is wide and deep with a myriad of variations. Close historical examination will reveal trends in critical embracement or shunning of jazz. There have always been critics of various colors who respected the music and the musicians enough to acknowledge the value of the music, even if the critic could not understand or appreciate it. There have also been plenty of critics who believed they “knew” what jazz was and “dogged out” musicians because the critic didn’t like it or think it worthy. I believe that is a form of cultural imperialism. Just because one does not like it doesn’t mean it isn’t good…and this is especially true in music.

AF: In Coltrane’s music I hear a great urgency, and your book helped me to see that this is two sided: an urgency that is at once political and spiritual. Do you hear the same kind of urgency in any of today’s jazz musicians? And what happens to jazz when we take away the yearning for spiritual transcendence on the one hand and political equality and inclusion on the other?

LB: Good questions here. As for the urgency in John’s music, that was unique to him — the uniqueness of his genius — and the times when he lived. I am not sure one can expect similar urgency in today’s times as things are different. I do believe that his intent to use music as force for good can and should be maintained now and on into the future. We certainly are in need of making the world a better place for all people. As for yearning for spiritual transcendence, that is a personal thing and should not be expected of any musician, jazz or otherwise. As for political equality and inclusion, those also reflect individual perspectives of musicians, who are human beings first. It is the musician’s choice as to whether she, he or they want to insert political equality ad inclusion into his/her/their music. It may be enough to work hard to continue to develop one’s musicianship and maintain a good sound.

AF: Who are the musicians right now who are most directly in the artistic line of descent from Coltrane? Kenny Garrett comes to mind. Others? Do those musicians also have the same kind of political and spiritual aims as Coltrane, and do they see the same kind of connection between politics and spirituality that Coltrane did and that is a large them running throughout your book?

LB: As to possible musical descendants of Coltrane, this is a dangerous question, as I would think that many have been influenced and that they, including me, understand that one must strive for one’s own sound. No doubt that many have benefited from Coltrane’s majestic excursions into vertical and modal improvisation, as well as spiritual enlightenment. That said, the descendants are not solely saxophonists or even jazz artists, and I would agree that Kenny is one. Coltrane’s legacy extends into other genres of music globally. I have no idea as to the political and spiritual aims of the musicians.

AF: One point the book makes in a few places is the influence on Coltrane of Ornette Coleman. I’ve read interviews with Coleman in which he doesn’t seem to see Coltrane as a major twentieth century figure. As a saxophonist, would you like to talk a little about Coltrane and Coleman, particularly the kind of “free jazz” practiced by them and the important differences you see between their approaches to “free jazz”?

LB: Well, Ornette is certainly one of the greatest artists of all time and he certainly had an impact on Coltrane, as both were seekers and innovators. I wonder about him supposedly not seeing Coltrane as a major 20th century figure. What is the source of that quote? And I wonder if he really said that, has he changed his mind, which is allowed you know. He certainly is entitled to his opinion. Many others would disagree, including me. As for “free jazz’, as Baraka said, free jazz = free blacks. Both these innovators manifested in the free jazz movement at a time that coincides with the civil rights and black nationalistic movements in the USA… maybe some cosmic equation that is beyond our understanding caused this to happen. From my view, both these masters came to an understanding that vertical or chordal approaches to creative improvisation could be limiting if and when one arrived at a certain state of mastery, consequently, they sought other approaches. Similarly the move to free the time from a definite or set meter was reflective of a very advanced state of musicianship. Also be aware that both Coltrane and Coleman studied, listened and were influenced by music and musicians from Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

AF: To what extent do you see a connection between your book and the JCMC?

LB: My insight into Coltrane’s musical and spiritual legacy has been enhanced and deepened through performing the great majority his music over the years. We have gone from Straight Street to Peace On Earth since 1977. No doubt that performing John’s music is central to the understanding I have gained. There is also the educational responsibility we took on in establishing the JCMC in 1977 and growing it over the years.

AF: What are some highlights of the JCMC over the years. What do you remember most fondly, and what do you think Coltrane would have most enjoyed or approved of?

LB: The highlights are too numerous to mention. It is rewarding to serve as a catalyst in bringing an outstanding group of musicians together for this annual tribute. Some of my fondest memories are the backstage gatherings of the musicians…the JCMC is like a family affair. There is a core group that is committed to keeping the concert going over the last 3 ½ decades! That’s a long time. And then there is the music…we have done so much of Coltrane’s music in so many varied and different ways, always striving to maintain the integrity we bring to the endeavor. And then there are the guests artists that you can find listed on the JCMC website www.jcmc.neu.edu as well as the Educational Outreach Program that brings elementary and secondary school students free to the concert since 1992.

AF: Please tell us about some of your other projects, especially those related to Coltrane.

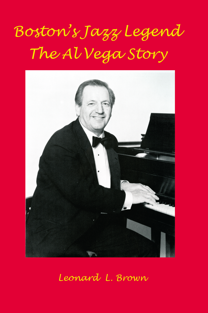

LB: Later this year, I will begin work editing a series of live recorded interviews with jazz greats conducted by Eric Jackson on his WGBH radio in the 1990’s. Nothing on Coltrane now. I self published a book on Boston jazz Legend Al Vega this past summer. It is titled Boston Jazz Legend: The Al Vega Story.

AF: What are your favorite Coltrane songs–your “favorite things”?

LB: All of them. I like early Trane, mid Trane and late Trane. I have a special affinity for his later things “Peace on Earth,” “Meditations,” “Love Supreme,” “Transition,” “Cosmic Music,” “Interstellar Space,” “Live in Japan,” “One Up One Down” – then there is “Live in Seattle” when they do “Body and Soul” and “Out of This World” in such expanded and cosmic interpretations. Both of his bands were such brilliant musical ensembles. If one listens closely, you can hear a new brilliance, confidence, excitement and joy that John brings to his recordings and performances after his epiphany in 1957 when he cleaned up and stopped using drugs, asked the Creator for help and studied and played with Monk. Things after that were not what they used to be.