Book Review: Getting Closer To Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman is an exuberant poet, and fellow versifier C. K. Williams is exuberant about Whitman in this wonderfully perceptive introduction to his poetry.

On Whitman (Writers on Writers) by C. K. Williams. Princeton University Press, 208 pages, $19.95

On Whitman (Writers on Writers) by C. K. Williams. Princeton University Press, 208 pages, $19.95

Reviewed by Anthony Wallace

On Whitman is a meditation on the life and work of the man many claim is the greatest American poet by a very good American poet, and one who is also pretty famously “Whitmanian,” or perhaps it’s “Whitmanesque.” The title seems intended to convey the personal essay quality of the book, published by Princeton University Press but intended for a general readership, although not completely general since Williams assumes that “anyone reading this book would keep a copy of Leaves of Grass at hand.” It’s a small book that can be read in two or three comfortable sittings—also a book to return to, to keep on the night table—and is organized according to topic, with such broad headings as “America,” “Sex,” “The Body,” “Prophets,” and the concluding “What He Teaches Us.” Williams grounds the book in his own observations, the product of a lifetime of reading Whitman, and he makes liberal use of the first person pronoun. Whitman is an exuberant poet, and Williams is exuberant about Whitman.

Approaching Leaves of Grass and the Various Editions

One might ask what is left to say about Walt Whitman, who “contains multitudes” and who also has generated multitudes: multitudes of studies, critical and otherwise, including a multi-part PBS documentary. Williams begins by answering that very question: “I felt the need to clear the air—to approach the poetry as I had when I first came across it, to try to reestablish and reconfirm the raw power of the poetry in the context it was making for itself on the page, not in the range of all that lay behind it.” He adds that it’s “the poetry, poetry, poetry that continues to astonish and inspire.” A tone of unapologetic wonderment runs throughout the book, is part of the frank subjectivity of the book, is contagious throughout the book, but is also a (slight) limitation of the book. In some ways, Williams pleads his case for Whitman’s greatness more vigorously and insistently than he needs to, and this also results in some oversimplification of how the miracle of Whitman’s poetry came about to begin with.

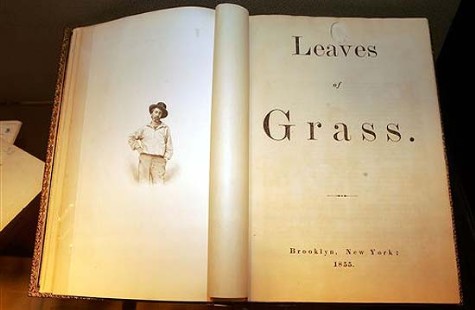

Williams makes one important exception, though, bringing in Malcolm Cowley to add his weight to the idea that the 1855 (first) edition of Leaves of Grass is “Whitman’s greatest work, and most poets, scholars, and readers have agreed.” Williams states pretty much as a fact that Leaves of Grass was essentially itself, in its best form, in 1855, that Whitman had one annus mirabilis, two at the most if you count important poems like “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” written in 1856 (Harold Bloom gives Whitman a more generous, and I think more accurate, 10 years of peak production), and that it was downhill, in some ways, from there with Whitman essentially tinkering with and sometimes undoing the perfection of the original for the rest of his life: “In my view, and in that of the poets I know, many of the changes Whitman made in later editions diluted and diffused his first brilliant inspirations.”

Whitman brought out changed and expanded editions of Leaves of Grass from 1856 until the so-called “deathbed edition” of 1891-1892. That is a long time to work on one book, and to argue that subsequent editions take the book in the wrong direction seems to contradict the almost constant assertion of Whitman’s greatness: Williams compares him to Homer, Shakespeare, and Dante. Williams doesn’t do anything with the idea that Whitman might have sacrificed the integrity of a single, strong poem for the good of the overall collection, or mixed stronger and weaker poems in a way that creates a stronger overall effect: a strategy that would be appropriately Democratic, the ideal upon which the entire Whitmanian enterprise is based. A howler like “O Captain! My Captain!,” for example, might be doing work that is much more subtle and complex relative to contiguous poems and their arrangement. In fact, in the “Preface” to Leaves of Grass Whitman sets up the tension between the individual and the group (the one and the many), a creative tension that aims at preserving the integrity of both—a Democratic ideal perhaps above all others—and Whitman develops this idea in a variety of ways throughout Leaves of Grass, including the relationship between form and content.

Williams does address the idea that Whitman’s breakthrough in one sense can be seen as the celebration of the “ordinary,” but he does not take the idea, as Whitman did with all of his ideas, to its utmost logical conclusion: that Whitman might very well have known some of the later poems were more “ordinary” and included them as such, or even deliberately have written them as such, in order to balance—another key word—masterpieces like “Song of Myself” and “By Blue Ontario’s Shore.” Williams also has not considered the possibility that “the Greatest Poet” (Whitman’s phrase) might not always and at every moment be concerned with writing “the greatest poem.” Whitman was after something bigger: an American Bible, an ongoing epic, not written and done with in 1855-56 but constantly growing and changing and evolving (like grass) along with its author and its author’s country. As such, it should come as no surprise that there are many editions, including a “deathbed edition,” that there is some falling off, some decay, much imperfection—”He could reveal the ill wrought and the well wrought of himself with equal fervor”—and that Whitman intended all this as an aspect of his fullest and most complete (while never entirely completed) expression.

In this way of reading Whitman, any edition of Leaves of Grass might also be seen as a part related to a greater whole, a system in which different editions of the book speak to one another and in which different versions of the same poem also speak to one another in their different forms and also from different places in different versions of the text. For Williams to argue for a more static or “finished” or “best” Leaves of Grass, it seems to me, is either to misunderstand the book(s) or to proclaim Whitman’s lifework a failure—either of which undermines his own position. For all Williams’ praise of Whitman’s genius, he seems to have sold the old man short, at least in this one very important regard.

The Poetry: Locating its Source and Participating in the Experience

Other places in the book Williams goes a bit too far in the other direction, and it sometimes seems as if Whitman has sprung, full blown and godlike, from his own head. But it is a disservice to the “general reader” to suggest, for example, that Whitman’s landmark experiments with free verse came in the proverbial lightning bolt and that there is little in the way of historical influence to account for them: “We have to give Whitman’s genius its due: he did something that the evidence is in no way able to predict no matter how scrupulously we scour through his predecessors.” Williams does mention Shakespeare, Homer, and the King James Bible as major stylistic influences but then concludes, because there is not a clear genealogical progression, that Whitman’s breakthrough is mysterious and that “because the evidence is so meager, there’s a point at which we have recourse to the notion of ‘genius.'”

In a later chapter, he brings in the raw material of Whitman’s notebooks and returns to the same idea: “some utterly mysterious thing happened in the psyche of the poet which still remains the unlikeliest miracle, and he discovered, created, his method.” In Leaves of Grass, Whitman wanted to create an American Bible, an American epic, as I’ve already mentioned, and to create himself as a national poet. These ideas were influenced by Emerson and are clearly set out in the “Preface,” and so it’s not such a leap, I don’t think, to suggest that he would consciously model his poetry on Homer, Shakespeare, and the Bible, or that those sources were the inspiration to begin with.

In the chapter titled “Emerson and the Greatest Poet,” Williams does discuss Emerson’s influence in some detail, but there is something in Williams’s admiration of Whitman that does not like to admit influence or debt—or even the simple historical fact that the older writer helped and encouraged the younger—and as soon as he mentions a point of contact between Emerson and Whitman he minimizes it, or maybe deflects is a better word.

In subsequent chapters, Williams moves on to Whitman’s politics, his family background, his homosexuality, and the Civil War. In the chapter titled “America,” he develops Whitman’s insistence on the vital connection between American poetry and American Democracy and points out, not unimportantly, that Whitman understood his country’s faults as well as its virtues. In his own sense of who he was and where he was starting from, Whitman was always an American; he used American materials to make his poetry (an idea taken directly from Emerson’s essay “The Poet”), and that idea is crucial to understanding the heart of Williams’ book: Whitman’s own marvelous self-creation, and how that is inseparable from the creation of the poetry: “Whitman’s poems made him; he existed in them in a way he existed nowhere else.”

Leaves of Grass—First Edition

Leaves of Grass—First Edition

Williams spends an appropriate amount of time on “Song of Myself” and does do a fine job of describing the complex, poetic persona Whitman has created, the poetic “I” that so many readers have responded to and been seduced by, and the complex process by which Whitman not only promises to give us real poetry but to “make poets of us all.” The process of his own poetic creation spills over into us, and we participate in it actively.

Poetry for Whitman was an act that could transform everything, including the reader: “We will again be first persons adequate to our greatest selves.” There is the poetic “I” in Whitman, but also the poetic “you,” and a “communion unlike any other in poetry,” something at once spiritual and sexual, up there and down here. This, Williams rightly suggests, is Whitman’s indelible contribution to poetry. Whitman has taken the poetic “I” of the lyric poem and expanded it, collapsed its boundaries, made it simultaneously lyric and epic, individual and cosmic. It becomes everything, and so do we.

When it comes to reading poetry, we usually do well to be guided by the poets, and Williams makes a fine guide. He quotes generously, and his commentary points us in the right direction but leaves plenty of room for our own response. Most importantly, he shows us the largeness of Whitman’s vision, how he took in the whole world and gave it back to us whole: “Whitman sometimes compared himself (with proper humility) to Shakespeare, and edged on toward Dante and even Homer. Of course he differs radically from all three, but in this sheer largeness, this huge digestion of numberless atoms and chunks of reality, he is in their camp, is one of them, with them.” Williams shows us how Whitman balanced the general with the particular, how the poetry breathes line by line, how he leaps wondrously from the physical to the metaphysical and back again, but I think his most important insight into the poetry is this:

But in fact what’s striking is that there are no “depths,” in Whitman, no secrets, no allegories, no symbols in the sense of one thing standing for another. [. . .] If something does stand for something else—the bird in “Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking,” for instance, or the lilac or thrush in “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d”—he tells us or all but tell us, it does [. . .] It would be foolhardy to read Whitman with an eye to Eliot’s “objective correlatives”—his notion of images embodying complex ideations—because nothing in the poems answers to that definition, although everything in them serves the same function of enrichment, of layering of response. The layers are all laid out on the page: the complexity of the response that’s demanded is the same Eliot described, but it’s a complexity, again, an equation, all of whose parts are revealed.

No tricks, as Whitman himself declared. No games, no crafty reversals. No irony. No sham meanings in a sham world. Everything is real in Whitman—real in the sense of being what it really is and the dignity that implies—and everything is there. Plenty on the first reading, always plenty to go back to, a poetry of plenty in the land of plenty. There is truly something in Leaves of Grass for everybody: again the Democratic ideal, always inclusion, never exclusion. This is something we need to know about Whitman as a starting point, and if we already know it, it’s still not bad to learn it again and to start over. Whitman leads us to Modernism in a way that helps us as readers and makes sense to us, but the reverse is not always true.

The Larger Context and Whitman in Our Own Time

Toward the middle of the book, Williams starts to bring other poets into the conversation, and the sense of an expanding context is welcome. Williams mentions the usual comparison between Whitman and Dickinson, the idea that together Whitman and Dickinson are the progenitors of modern American poetry, a line of thinking he calls “reflexive.” He rightly claims that Whitman’s influence has been substantially larger than Dickinson’s, and then moves into an interesting and unexpected comparison of Whitman to one of his French contemporaries, Charles Baudelaire. Both poets, Williams claims, “redefined the elemental project of poetry, and both, to a great extent, indicated the direction, the opportunities, and the parameters of what we now call the modern.” Williams sets up many interesting parallels, ending with this one: even as Baudelaire was dogged by the greater popularity and commercial success of Victor Hugo, Whitman was dogged by Longfellow. This is the place in the book where the author begins to locate Whitman and his innovations in trends and patterns larger than himself, and to think of Whitman in historical terms is to think of him, oddly enough, in more directly human terms, which is one way to balance his sometimes godlike poetic persona.

Walt Whitman: We still haven’t given his genius its due.

I was also happy to see Williams address Whitman’s influence on T. S. Eliot, a connection too few critics have bothered to investigate. Williams doesn’t mention Harold Bloom, who has written about the connection between Eliot and Whitman in ways even more specific and, to my mind, compelling. He goes much further than Bloom though, to claim that Eliot found in Whitman’s free verse the techniques of dissociation and radical juxtaposition he would use so well in his own poetry, and that in fact Pound learned them from Eliot once Eliot had learned them from Whitman! Williams states it flatly, no irony: “The truth is that despite his bloviating, the very essence of Eliot’s poetical method is based on Whitman’s.”

I am happy to give Walt Whitman credit for some of the most important innovations in 20th century Modernist poetry, but Williams does not give us much evidence except to say, as he frequently does, that to his knowledge nothing like that had been done before Whitman did it. And, in an omission just as glaring, he does almost nothing to address Eliot’s debt to French Symbolist poetry—even though Baudelaire is already in the conversation—except to say that “the way he [Eliot] actually put together his poems is found in none of them [the French Symbolists] but is effectively realized in Whitman.” Case closed!

Williams goes on to talk about obvious influences on other famous twentieth-century poets like Pablo Neruda and Allen Ginsberg. From there it’s wisely back to the poetry, with attention to seemingly contemporary themes like “The Body,” “Sex,” “Woman,” and “Lorca, Ginsberg, and The Faggots,'” and from there to other key themes and motifs in the poetry. Because the book is based on a fairly broad although persuasive reading of Whitman’s poetry, it starts to become repetitious and loses some momentum, especially in the last third. The enthusiasm for Whitman that we started with becomes a bit strained in Williams’s insistence on it. But it is “the poetry, the poetry, the poetry” that keeps Williams’ book moving forward, and we do continue to get important insights into how we should read Whitman, ending with “What He Teaches Us.”: Whitman “remains in many ways our poet, the poet of our culture, our political and social identity and history. He remains startlingly close to us in his basic concerns: he sees and hears much as we do, but he demonstrates for us how to see and hear more attentively, sympathetically, accurately. Most crucially, in his ever-refreshing, ever-renewing music, he is with us, he is here.”

“Closer yet I approach you,” Whitman writes in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” and Williams does bring us closer to America’s poet, mainly by helping America’s poet come closer to us. That is the heart of Whitman’s poetic enterprise, and that is the heart of On Whitman. In 187 small pages, C. K. Williams has given us a wonderfully sweeping and perceptive introduction to the poetry of Walt Whitman, his major themes, patterns, and innovations, those who influenced him and those whom he influenced in turn, a bit of his life and times, a little history, and a little gossip. There is something in this book, too, for everybody, but best of all is that Williams has taught us to approach the poetry better, to appreciate better Whitman’s “language music,” to embrace it, to let ourselves be embraced by it, to touch and be touched, and if he insists a little too hard that we should all stand and gape in simple wonderment at the miracle, all right, the American miracle that is Walt Whitman—well, and so we should.

Anthony Wallace teaches in the College of Arts and Sciences Writing Program at Boston University and has published short fiction and poetry in such journals as CutBank, Another Chicago Magazine, and the Atlanta Review. He has new work forthcoming in The Republic of Letters.

Tagged: American poetry, Anthony Wallace, C. K. Williams, On Whitman, Poetry, Princeton University Press

My favorite comment on Whitman is Randall Jarrell commenting on some lines from a Whitman poem: “There are faults in this passage, and they do not matter: the serious truth, the complete realization of these last lines make us remember that few poets have shown more of the tears of things, and the joy of things, and of the reality beneath either tears or joy.”