Arts Feature: Recommended Books, 2024

Compiled by Bill Marx

An eclectic roundup of the favorite books of the year from our critics.

Tess Lewis

Excess was a recurring theme, if not outright aspiration, in much of my reading in 2024. In March, Becca Rothfeld’s bracing essay collection All Things Are Too Small set a promising tone for the year, with her call to shake off the pinched aesthetics of Marie Kondo and embrace extravagance and obsession in art. Opinionated and discerning, Rothfeld’s no-hold- barred criticism will set your pulse and your mind racing.

Another expansive and incisive critical mind is at work in Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel by Edwin Frank. This engaging group biography of the novel in the last century takes flight (or starts digging) in 1864 with Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and lands (or comes up for air) in 2001 with W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. Frank makes no claim to comprehensiveness — he limits his choice of books to those that help him tell “the story of an exploding form in an exploding world” and that shaped him as a reader — so it’s not particularly instructive to indulge in “what about…?” questions. Still, I wish he’d given Thomas Bernhard a bit more of a role in the story.

Another expansive and incisive critical mind is at work in Stranger than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel by Edwin Frank. This engaging group biography of the novel in the last century takes flight (or starts digging) in 1864 with Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground and lands (or comes up for air) in 2001 with W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. Frank makes no claim to comprehensiveness — he limits his choice of books to those that help him tell “the story of an exploding form in an exploding world” and that shaped him as a reader — so it’s not particularly instructive to indulge in “what about…?” questions. Still, I wish he’d given Thomas Bernhard a bit more of a role in the story.

While Bernhard has spawned legions of imitators and acolytes, some decidedly more derivative than others, those writers who can thoroughly digest and assimilate his dyspeptic, obsessive style to their own are often the better for it. Two novels bearing Bernhard’s salutary imprint appeared this year. The first is Adam Ehrlich Sachs’s novel of interconnected stories. Gretel and the Great War is a fever-dream of Vienna, the beating heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the run-up to the First World War. These stories, with their atmosphere of enchantment and strong currents of cruelty, read like fairy tales. However, these are no innocent bedtime stories, but neatly intertwined, fantastical reflections of the dominant psychological, artistic, social, and political ideas in Austro-Hungary in the first decades of the 20th century. Although their names aren’t mentioned, the shades of Adolf Loos, Egon Schiele, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Karl Kraus, Theodor Herzl, and other visionary and uncompromising thinkers and artists flit through these pages. Sachs’s focus on the obsessions and absurdities of aesthetic absolutists and intellectual purists is a clear echo of Bernhard, although Sachs brings both greater whimsy and more explicit cruelty to their manias.

Lesser Ruins, the second exhilarating Bernhardian novel of the year and Mark Haber’s third, follows the inner monologue of a newly widowed philosophy professor placed on administrative probation as his thoughts swirl manically and maniacally around a long-planned and always deferred book-length essay on Montaigne, the exultation coffee brings him, the toll of distraction, and a clutch of amusing digressions. Roiling underneath the already seething surface of his sentences is a strong current of grief that has been threatening to overwhelm him. This brings a sharp poignancy to the novel that tugs at the reader’s heart.

Dana Gioia’s collection of pieces on opera and poetry Weep, Shudder, Die is a fitting endpiece to this bare-bones survey of current literary extravagance. Gioia makes a strong case for the libretto as a crucial, rather than secondary element of opera, insisting that the “libretto is not a shabby coat rack on which the magnificent vestments of music are hung.” He points out that “twenty-four of the fifty most frequently performed operas are the work of only eight poets,” and his focus on the words as well as the music of operas — some war horses, some less familiar — make the reader want to rush to the nearest opera house or streaming site. Gioia is a genial and deeply knowledgeable guide, and his passion for “the extravagant and alluring art of opera” is infectious.

Dana Gioia’s collection of pieces on opera and poetry Weep, Shudder, Die is a fitting endpiece to this bare-bones survey of current literary extravagance. Gioia makes a strong case for the libretto as a crucial, rather than secondary element of opera, insisting that the “libretto is not a shabby coat rack on which the magnificent vestments of music are hung.” He points out that “twenty-four of the fifty most frequently performed operas are the work of only eight poets,” and his focus on the words as well as the music of operas — some war horses, some less familiar — make the reader want to rush to the nearest opera house or streaming site. Gioia is a genial and deeply knowledgeable guide, and his passion for “the extravagant and alluring art of opera” is infectious.

Gioia points out, reasonably enough, that “opera lovers want ecstasy, not instruction.” And so, I’d add, do many readers of fiction; at least this one does.

Vincent Czyz

Tamas Dobozy’s short stories are consistently off-beat, unsettling, and superbly written. Stasio, his first novel, is a first-rate example of fiction noir that upholds the literary standards Dobozy set for himself. In keeping with the genre’s conventions, the novel’s settings are bleak and gloomy, the weather perpetually gray. Unlike Hercule Poirot or Sherlock Holmes, however, Anthony de Stasio, a detective in the Canadian city of Kitchener, is deeply flawed, not just as a person but in his investigative methodology as well. He’s also far more believable. So are Stasio’s cases, whose endings resist the neat conclusions characteristic of detective fiction — maddening kernels of ambiguity always seem to remain. Distinguished by Dobozy’s lyricism, crisp dialogue, and humor, by well-drawn characters and the intellectual depth we expect from our best writers, Stasio is a haunted narrative that, when the pitch is right, is also haunting. Arts Fuse review

Kai Maristed

A Few Very Good Books to give in 2024 or Any Other Time. Dates are for English translations where relevant.

The Wizard of the Kremlin by Giuliano da Empoli (2024). Engrossing fiction illuminated by the author’s experience in the titular fortress. If you want to know who Putin is and how he got there, this is your guide.

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami (2008). Filled with startling, moving, amusing personal insights about both running and the writer’s craft and vocation, and how they intertwine to create the irrepressible force that is Murakami. Highly recommended as an audiobook while jogging.

The Road from Belhaven by Margot Livesey (2024). Wonderfully tender and evocative of the comforts and cruelties of an earlier time and hard-scrabble place in rural Scotland. With her usual tact Livesey lets her heroine seek her way independently, while readers cross their fingers and hold their breath. (Nb: Livesey and I are colleagues.) Arts Fuse review

Annihilation by Michel Houellebecq (2024). Critics can and do flay him; many did for this novel — but Houellebecq remains a huge pop favorite in France, despite the ire and convolution of many of his novels. Annihilation is convoluted, but also as socially/politically insightful as de Tocqueville and much funnier. Satire is MH’s middle name. Here he also bares his heart, and though I don’t agree with his cause, he makes a strong case.

Annihilation by Michel Houellebecq (2024). Critics can and do flay him; many did for this novel — but Houellebecq remains a huge pop favorite in France, despite the ire and convolution of many of his novels. Annihilation is convoluted, but also as socially/politically insightful as de Tocqueville and much funnier. Satire is MH’s middle name. Here he also bares his heart, and though I don’t agree with his cause, he makes a strong case.

Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü, (2023) winner of the 2024 Barrios Prize for Translation. Published six years before her death at 43, Cold Nights of Childhood established Özlü as the ”melancholy princess” of Turkish literature. From the orchards of a rural childhood to the cafes of European capitals, Cold Nights offers a sexually frank portrayal of a woman justifying desire in the face a punitive patriarchy.

Aliss at the Fire by John Fosse (2022). One suspects that even inveterate readers have quailed at the prospect of reading 2023 Nobelist Fosse, whose books pretty much run without punctuation. Aliss is shorter than most, and while strange at first, will pull you in like the irresistible ebb tide of a fjord.

The Miro Worm and the Mysteries of Writing by Sven Birkerts (2024). Essays on language, writing, and the meaning of self. (Chat GPT eat your nonexistent heart out.) A tall glass of distilled wisdom by the longtime editor of AGNI magazine, served with a sometimes wry twist. To writers and readers alike, Sköl! Arts Fuse review

Roberta Silman

As 2024 draws to a close I would like to recommend some books that will nourish you in these chaotic times.

Letters, Oliver Sacks, Knopf, 726 pages. Oliver Sacks was one of the most interesting men in modern times. He lived from 1933 until 2015 and published a multitude of volumes having to do with his work in neurology. He also published books about his own fascinating life as a gay doctor, born in London to a Jewish family of doctors, and forced to live on the fringes of society both in England and in this country. This assemblage of letters usefully augments his autobiography, On the Move, because it gives us more of the texture of his remarkable life, his remarkable intelligence, and his remarkable talent as a writer.

Small Acts of Courage, A Legacy of Endurance and the Fight for Democracy, Ali Velshi, St. Martin’s Press, 2024, 289 pages. As one gets older one often ends up watching more news and feeling closer to some of the news anchors. That is what happened to me with Ali Velshi, who anchors a weekend show on MSNBC that I love. So when this book came out, I immediately read it and learned more about Ali’s family and their unique journey from South Africa to Kenya (where he was born) to Canada. This is a wonderful, inspiring book about resilience and a family’s fierce devotion to democracy. A great gift for a young person.

Small Acts of Courage, A Legacy of Endurance and the Fight for Democracy, Ali Velshi, St. Martin’s Press, 2024, 289 pages. As one gets older one often ends up watching more news and feeling closer to some of the news anchors. That is what happened to me with Ali Velshi, who anchors a weekend show on MSNBC that I love. So when this book came out, I immediately read it and learned more about Ali’s family and their unique journey from South Africa to Kenya (where he was born) to Canada. This is a wonderful, inspiring book about resilience and a family’s fierce devotion to democracy. A great gift for a young person.

An Angel at My Table, The Complete Autobiography, Janet Frame, Counterpoint, 2017, 579 pages, $21.95. 2024 was the centenary of the great New Zealand writer Janet Frame. This is a terrific book — Patrick White called the first two volumes “one of the wonders of the world” — which I was inspired to pick up after Arts Fuse editor Bill Marx recommended the movie by Jane Campion based on it. An Angel at My Table is, indeed, a fabulous book about a uniquely quirky life.

And from the books I reviewed in 2024, I would like to recommend anything by the great essayist Joan Acocella and the Malaysian fiction writer Tan Twan Eng and the first novel How to Build a Boat by Elaine Feeney. I also recommend the work of the new young Italian writer, Andrea Marcolongo.

Lastly, because I needed something to calm myself after the election, I reread My Ántonia by Willa Cather, which was one of the first books I read in my freshman American lit class at Cornell. It is well worth reading and rereading and giving to the young.

David Daniel

Breslin: Essential Writings, edited by Dan Barry. The Library of America, 723 pages, $40.

Ace journalist Jimmy Breslin once remarked that he gave up writing a newspaper column because he “got tired of seeing my stuff on the subway floor.” For anyone who had the good fortune to read him in newsprint, or those discovering him for the first time, this book is a testament to a three-times-per-week deadline artist who gave voice to the powerless and underprivileged. Arts Fuse review

Preston Gralla

It was a bad year for politics. But there is one consolation: it was a great one for fiction, one in which the novelist Percival Everett got his just recognition with a National Book Award for fiction. So, if you need to reconnect with your better self, dip into this list.

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar. An Iranian-American man devoting his life to dying as a martyr may seem like a clichéd trope, but the poet Kaveh Akbar turns it on its ear in this complex, moving book. Its protagonist, Cyrus Shams, is a recovering addict. He’s also gay passing for straight, desperately unhappy, and adrift until he finds a purpose — to become a martyr. He papers his walls with photos of them, including Bobby Sands, Joan of Arc, and the anticolonial revolutionary Bhagat Singh. This strange premise yields a book that critics have called “incandescent,” “full-throated,” and “life-affirming.” It’s all that and more.

Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino. Here’s another book that turns a clichéd-sounding setup upside down. And the result is one of the most surprising and unique books of not just this year but any year. The plot: Adino Giorno believes she is an alien from another planet, planted in her mother’s womb to find out, once she’s born, about life on earth and report back to her superiors whether the planet is suitable for colonization. Her means of communication: A fax machine. Her life, though, is very much tied to this earth. Of course, you might suspect that she isn’t really an alien, but only feels like one — someone literally suffering from alienation. She’s vulnerable, confused, unsure of herself, and for almost every moment of her life feels estranged from existence — the makings of so much great literature.

James by Percival Everett. Everett has been writing sharp, pointed novels for four decades. He’s received critical acclaim along the way, but not nearly as much public notice. That’s not surprising; some of his novels, often satirical and sometimes chilly, have been easier to admire than to love. That should not be surprising, given that Everett describes himself as “pathologically ironic.”

His latest book, though ironic, is much more than that. It retells Huckleberry Finn from Jim’s point of view, with a twist: His writing, speech, and thoughts are literate, sophisticated, learned, and intelligent — far beyond the rather caricatured accents and slang in Twain’s version. And James isn’t alone. Every slave and Black in the book writes, speaks, and thinks in the same sophisticated way. They’re forced to hide their smarts from the whites who enslave them, lest the dimwitted masters take revenge.

But James is much more than the equivalent of a literary parlor trick — it’s deeply felt and with much to say not just about racism, but what it means to be a human. Everett pulls this off, all the while making his narrative an homage to the original. There’s a good reason it won the National Book Award. It should have won the Pulitzer as well.

Godwin by Joseph O’Neill. In a sports-mad world, it’s puzzling that so few writers have mined athletic subcultures for literary gold. O’Neill is a notable exception. A cricket club was at the center of a previous novel, Netherland. This time around, it’s a quixotic hunt for a young African soccer phenom who may or may not exist. The search for the elusive prey becomes a Moby Dick-like saga, with echoes of imperialist designs on the continent dovetailed with a confusing trail full of false leads and strange coincidences. There’s plenty of tech workplace drama thrown in as well. You might think this everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink approach would be too much. But it isn’t — the mix flat-out works.

Intermezzo by Sally Rooney. No one writes better about love than the Irish novelist Sally Rooney. It’s become fashionable among some literary types to denigrate her, to claim that her writing is trite, lacks bite, and is too soft. But it’s easy for these critics to admire authors who revel in cheap irony rather than praise a writer who portrays the glories and pain of falling in and out of love in a clear-eyed and honest way. Rooney does all that in this book, and more. It’s the story of two brothers grieving for their recently deceased father, and how they find or don’t find love. I find her writing in this book, as with her others, startlingly beautiful, always precise, and immensely moving. So, I guess you can call me a softie. But I’m far from alone. The New York Times critic Dwight Garner puts it this way: “She writes as well about [love] as anyone alive. It’s as if she were Iris Murdoch or Edna O’Brien with a three-book deal at Harlequin Romance.” I’m with him. If you’re smart, you will be, too.

The Hypocrite by Jo Hamya. In the last decade or so, white males of a certain age have not merely lost their cultural cachet, but have been roundly excoriated for countless vices, not the least among them misogyny, racism, and undue self-regard. There have been far too many vitriolic words thrown around between the case for or against, too much heat and too little light.

Not so in this book, in which a young up-and-coming woman playwright stages a play based on her father, who at first glance is a clueless, entitled white male writer from another era, full of misogyny and ego. He profited well from these attitudes. It would have been easy for Hamya to mine this setup for predictable laughs by skewering the aging novelist while valorizing his daughter. But, although there are plenty of barbs along the way, this novel is after something deeper: an honest portrayal of two generations of artists who sometimes love each other and sometimes despise each other. There’s pain along the way, as well as modulated satire of all concerned and no easy answers. Just like most of life.

Bill Marx

I have become fascinated by the idea of denial. We know, but repress, the fact that when we buy from Amazon, we (and our economy and its workers) pay a high price for the low price of convenience — yet we do it. And our response to the climate change crisis is even more intriguingly short-circuited: we know that it is happening, yet we don’t know — or routinely act as if we don’t know. The most provocative work of literary criticism I read this year examined the different forms that this phenomenon of knowing/not knowing can take: Allen MacDuffie’s Climate of Denial: Darwin, Climate Change, and the Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century (Stanford University Press, 281 pages). Secular humanists such as H.G. Wells, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf appeared to accept — but could not really accept — the fact that Darwin’s theory of a nonteleological evolution reduced mankind to the status of animals. These liberal writers could not comfortably acknowledge that scientific truth, so they found ways in their fiction to assert, once again, that we stand well above nature, which is classified as a realm fit for exploitation and commodification. Trenchantly written and politically relevant (it examines the roots of today’s defensive strategies), with a brilliant chapter on one of my favorite books, H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau.

I have become fascinated by the idea of denial. We know, but repress, the fact that when we buy from Amazon, we (and our economy and its workers) pay a high price for the low price of convenience — yet we do it. And our response to the climate change crisis is even more intriguingly short-circuited: we know that it is happening, yet we don’t know — or routinely act as if we don’t know. The most provocative work of literary criticism I read this year examined the different forms that this phenomenon of knowing/not knowing can take: Allen MacDuffie’s Climate of Denial: Darwin, Climate Change, and the Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century (Stanford University Press, 281 pages). Secular humanists such as H.G. Wells, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf appeared to accept — but could not really accept — the fact that Darwin’s theory of a nonteleological evolution reduced mankind to the status of animals. These liberal writers could not comfortably acknowledge that scientific truth, so they found ways in their fiction to assert, once again, that we stand well above nature, which is classified as a realm fit for exploitation and commodification. Trenchantly written and politically relevant (it examines the roots of today’s defensive strategies), with a brilliant chapter on one of my favorite books, H.G. Wells’s The Island of Doctor Moreau.

The best volume on the Bard I have read since Emma Smith’s This Is Shakespeare, Rhodri Lewis’s Shakespeare’s Tragic Art (Princeton University Press, 381 pages), is a formidably dense but illuminating attempt to survey the tragedies from a unified perspective, seeing them as the means, through the distinctive powers of drama, to clarify our vision by moving us beyond “misconceptions about the human condition.” For Lewis, the plays are “a series of experiments in which he [Shakespeare] pulls his art this way and that in the conjoined attempts to represent the particularities of the world as they appear to him, and to discover how far tragic representation can be stretched in order to accommodate the darker aspects of this vision. What is more, Shakespeare wants us to infer that dramatic art might help us to understand our place within the miserably compromised situations that it depicts. Tentatively, perhaps, to contemplate the possibility of moving beyond it.” I wish Lewis had grappled more fully with the nihilism of Timon of Athens (Shakespeare may have turned his back on this repudiation of human life, but he did write the play), but this is a valuable critical work that sees the Bard as a “temperamental skepticist” whose mission is more diagnostic than it is didactic: this Shakespeare is of particular use in our current addiction to the blind alleys of dogma.

The best volume on the Bard I have read since Emma Smith’s This Is Shakespeare, Rhodri Lewis’s Shakespeare’s Tragic Art (Princeton University Press, 381 pages), is a formidably dense but illuminating attempt to survey the tragedies from a unified perspective, seeing them as the means, through the distinctive powers of drama, to clarify our vision by moving us beyond “misconceptions about the human condition.” For Lewis, the plays are “a series of experiments in which he [Shakespeare] pulls his art this way and that in the conjoined attempts to represent the particularities of the world as they appear to him, and to discover how far tragic representation can be stretched in order to accommodate the darker aspects of this vision. What is more, Shakespeare wants us to infer that dramatic art might help us to understand our place within the miserably compromised situations that it depicts. Tentatively, perhaps, to contemplate the possibility of moving beyond it.” I wish Lewis had grappled more fully with the nihilism of Timon of Athens (Shakespeare may have turned his back on this repudiation of human life, but he did write the play), but this is a valuable critical work that sees the Bard as a “temperamental skepticist” whose mission is more diagnostic than it is didactic: this Shakespeare is of particular use in our current addiction to the blind alleys of dogma.

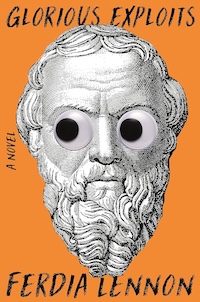

Some critics have found the humor in this debut novel too sitcom-ish, but Ferdia Lennon’s Glorious Exploits (Holt, 289 pages) serves up historical political farce just the way I like it: rowdy, brutal, despairing, vaudevillian, and, at times, tasteless. The setup’s meta-theatrical panache is also admirable. We are in ancient Greece — on the island of Sicily during the Peloponnesian War — but our narrators talk like contemporary Dubliners (a pair of lackluster potters) who figure that a prison quarry populated by captured Athenians would be the perfect place for creating some sadistic sport. They settle on having the powerless mount a production of Euripides’s Medea, an effort that becomes improbably inspirational, but also goes dangerously off the rails, in Aristophanes-like fashion, for the slaves and their masters.

Some critics have found the humor in this debut novel too sitcom-ish, but Ferdia Lennon’s Glorious Exploits (Holt, 289 pages) serves up historical political farce just the way I like it: rowdy, brutal, despairing, vaudevillian, and, at times, tasteless. The setup’s meta-theatrical panache is also admirable. We are in ancient Greece — on the island of Sicily during the Peloponnesian War — but our narrators talk like contemporary Dubliners (a pair of lackluster potters) who figure that a prison quarry populated by captured Athenians would be the perfect place for creating some sadistic sport. They settle on having the powerless mount a production of Euripides’s Medea, an effort that becomes improbably inspirational, but also goes dangerously off the rails, in Aristophanes-like fashion, for the slaves and their masters.

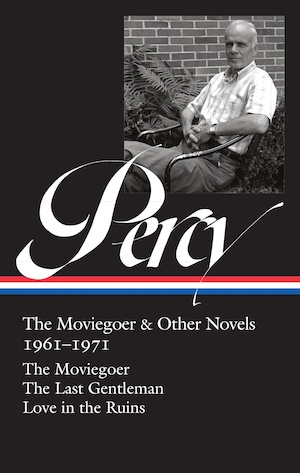

Finally, it was heartening that earlier this year the Library of America published Walker Percy: The Moviegoer & Other Novels 1961-1971. For me, this Catholic Southern writer, who trained as a physician at Columbia University, is a major postwar American novelist whose satiric/philosophical vision can be off-putting, mainly because it stands in refreshing opposition to the psychological/medicinal approach of so much homegrown fiction.

Finally, it was heartening that earlier this year the Library of America published Walker Percy: The Moviegoer & Other Novels 1961-1971. For me, this Catholic Southern writer, who trained as a physician at Columbia University, is a major postwar American novelist whose satiric/philosophical vision can be off-putting, mainly because it stands in refreshing opposition to the psychological/medicinal approach of so much homegrown fiction.

The three powerful books in this compendium explore a peculiarly modern spiritual predicament, an inertia whose pacifying source lies in the postwar tidal wave of national and individual possibility. Percy’s first book, The Moviegoer, won a National Book Award in 1961: it sets out his cultural diagnosis via a protagonist whose hollowed-out psyche (a soul caught betwixt and between) is symptomatic of the kind of paralysis found in the land of ever more, where you can be or do everything or just plain nothing. A sentence in Percy’s second novel, The Last Gentleman (1966), a compelling semi-autobiographical follow-up to the first, sums it up: “The vacuum of his own potentiality howled around him.” The third book in the LOA volume is the prescient (and highly amusing) faux-apocalyptic novel Love in the Ruins (1971).

Percy is part of the crazed American version of black comedy: the line runs from Herman Melville and Nathaniel West to the unjustly neglected absurdists of Percy’s generation — John Barth, Robert Coover, and John Hawkes — to David Foster Wallace. Now we need a second LOA volume that includes Percy’s scary investigation of the existence of evil, Lancelot (1977), and his inspiring essays on semiotics, particularly those in his 1975 volume The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other, in which Percy argues that we are overlooking, at our peril, the deep, existential impact that language acquisition has on the development of humanity, the elemental ways in which words connect us to the world.

Tagged: Bill-Marx, David Daniel, Kai Maristed, Preston Gralla, Tess Lewis

Thanks of this reprise of books selected for 2024. It’s always useful to have a checklist of good stuff that can get overlooked. Will be happy to see what a 2025 list looks like.