Book Review: “How to Build a Boat” — A Novel That Breaks and Lifts the Heart

By Roberta Silman

This splendid book should be read by every child and adult who is convinced he doesn’t “fit in.”

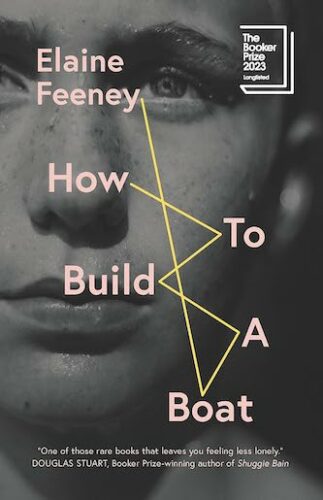

How to Build a Boat by Elaine Feeney. Biblioasis, 298 pages, $18.95

This is a wonderful book about growing up, about a very young father raising his son, about the importance of school and its often special teachers, and about how much a caring community can contribute to a child’s life. We talk blithely of how “it takes a village,” but do we really know what that means? The Irish writer Elaine Feeney explores its many layers in her second novel, a work of such depth and compassion that it was no surprise to learn that it was on the Long List for last year’s Booker prize.

This is a wonderful book about growing up, about a very young father raising his son, about the importance of school and its often special teachers, and about how much a caring community can contribute to a child’s life. We talk blithely of how “it takes a village,” but do we really know what that means? The Irish writer Elaine Feeney explores its many layers in her second novel, a work of such depth and compassion that it was no surprise to learn that it was on the Long List for last year’s Booker prize.

Feeney is now in her mid-40s, was born in the west of Ireland, has an earlier well-received novel called As You Were, and is also known as a poet. Like her compatriot Claire Keegan, she has an almost uncanny knowledge of the nooks and crannies of Irish life. Here she explores the aftermath of a high school love affair between Noelle Doyle, the school’s pride and joy in every swimming competition, and her boyfriend Eoin O’Neill — the kind of tragedy most people want to forget about, but never really can. In the Prologue we learn that about an hour after giving birth to Jamie, “surrounded by her large family, she [Noelle] died.”

Her family tumbled out through the doors in blind anger, and screamed at Eoin who held the baby tightly in his arms. One of Noelle’s sisters … spat at him, then lunged at him in a half-hug, half-punch, common with grief until the security guards separated them and he was still holding the baby when the family walked out of the hospital without looking back or noticing that underneath the small hat on his head Jamie O’Neill had a mass of auburn hair and furrowed brow, just like his mother.

Thus, Eoin is left to raise the boy on his own, with the help of his mother Marie, who lives nearby. But the pain of losing Noelle is too much to bear, so one night Eoin deletes all the clips he has of Noelle on his phone. Except one, which actually finds its way to the school’s website: Noelle warming up as she prepares to swim a race. Two minutes and eight seconds is all that is left of that vibrant beautiful creature whom Eoin loved so much. Two minutes and eight seconds which Jamie first sees when he is seven and which he watches obsessively over time, because it is all he has of his dead mother, whom he wants so desperately to know.

Fast forward into the book which begins when Jamie is 13 and about to start secondary school (eighth grade in the US). This proves to be a daunting new adventure for a highly intelligent child who has so many interests and so much curiosity. He is socially awkward, regarded by others as “different.” He is a precocious child mesmerized by YouTube clips of the great Iranian mathematician and Fields Medalist Maryam Mirzikhani (who died so tragically of cancer at only 40) and obsessed with finding a special hue of the color red. He is a great reader of Edgar Allan Poe and watcher of the films of Quentin Tarantino. He is also a child fixated on creating a Perpetual Motion Machine that will somehow recreate his mother’s “energy” and connect her to him. He sings to calm himself and cannot comprehend why his volatile and quirky intelligence makes him such inviting prey for the bullies, including the headmaster. If Jamie’s situation sounds a little frantic, it is. Yet in Feeney’s hands How to Build a Boat is a constantly fascinating and urgent journey which alternately breaks and lifts the heart.

Parallel to the story of Jamie is the story of one of his teachers, Tess Mahon, who is in a troubled marriage yet trying to conceive a child. As she befriends this boy who needs her so much, she begins to free herself from the bonds she thought had to remain permanent. Here she is only two months after term has begun:

She was more and more uncertain about her own future, and listening to Jamie rattle on about life and what everything in any given day might mean, his desire to find the interconnection in every random set of occurrences, made her realise how much she was missing out on—in an effort to keep peace, or just to avoid drama. She was beginning to realise that by avoiding drama she was headed for an almighty crash. And how she had switched off entirely from looking for any beauty in the world.

But drama is what keeps the world turning, and as Tess gets to know Jamie better she also forms bonds with her colleague, Tadhg Foley, (the woodworking teacher). So this child who has crept into the reader’s bones also becomes the catalyst for a deep connection between these two adults who lost parents when they were very young and whose fear of the world is slowly giving way to a better understanding of themselves.

Feeney is a fabulous writer, unafraid to take risks or make transitions with no warning. Because she does not use quotation marks for speech (like another master, Grace Paley), the prose veers and swerves in unexpected directions, requiring absolute attention on the part of the reader. Because of this we find ourselves “living” in this book, in just the way that Hemingway intended when he talked about what he hoped to do when writing his early short stories.

We watch Jamie interact with his devoted father and grandmother, we see his fierce independence help change some of his classmates, we experience his hurt when he is excluded and cheer for him when Tadgh decides that having Jamie design and build a currach — a small round boat made of wickerwork covered with a watertight material, propelled with a paddle — will channel his enormous and sometimes exasperating energy into something tangible and meaningful. It is a brilliant stroke, not least because water hovers over the novel in myriad ways, but also because it brings together the community for a triumphant finish. Jamie takes the boat on the water for his 14th birthday, and the beautiful Epilogue — really a prose poem — is a fitting end to this stunning book.

This is a book that should be read by every child and adult who is convinced he doesn’t “fit in.” A book whose allusions and concerns broaden our view of the world. A book that fulfills the promise of its epigraph from Maryam Mirzikhani: “There are times I’m in a big forest and I don’t know where I’m going. But then somehow I come to the top of a hill and I can see everything more clearly. When that happens it is really exciting.”

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, a short story collection, and two children’s books. Her latest, Summer Lightning, has been released as a paperback, an ebook, and an audio book. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review) is in its second printing and is available on Amazon. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com, and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.