March Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Books

Jonathan D. Katz is a pioneering historian working in queer and gender studies. In 2019, he curated About Face: Stonewall, Revolt, and New Queer Art for Chicago’s Wrightwood 659 Gallery’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Stonewall. About Face featured over 350 artworks by 38 LGBTQ+ international artists.

Jonathan D. Katz is a pioneering historian working in queer and gender studies. In 2019, he curated About Face: Stonewall, Revolt, and New Queer Art for Chicago’s Wrightwood 659 Gallery’s commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Stonewall. About Face featured over 350 artworks by 38 LGBTQ+ international artists.

Focusing on underrecognized interracial and multigendered artists across generations, Katz assortment challenged the prevailing prejudices of homonormativity, which overlooks BIPOC and trans folks in favor of assimilated white and cisgendered people. The show was a self-conscious provocation, an attempt to revise the LGBTQ+ canon.

The recently published catalogue for About Face (Monacelli Press, 272 pages, $65) includes elucidating essays and texts by Julian Carter, Anthony Cianciolo, Amelia Jones, Ava L.J. Kim, Joshua Chambers-Letson, Christopher Reed, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Dagmawi Woubshet. This lushly designed book — there are 300 illustrations — offers proof of concept for Katz’s curatorial vision of the ever-evolving hybrid intersectionality of queer aesthetics.

Such well-known American artists as Nick Cave, Keith Haring, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Peter Hujar are included. More significant, given Katz’s revisionist approach, are the appearances of installation artist Tianzhuo Chen, Leonard Suryajaya’s color-saturated photographs, Bhupen Khakhar’s figurative paintings, and the performative tableaus of Keioui Keijaun Thomas and Del Lagrace Volcano.

Other highlights in the volume confront the art world’s systemic racism; these include Jacolby Satterwhite’s immersive 3D animated media creations inspired by gaming, as well as South African photographer Zanele Muholi, and Canadian Cree interdisciplinary performance artist Kent Monkman.

The primary focus of About Face is on the new, but the work of deceased artists add welcome depth to the tapestry. The Bay Area is represented by Harvey Milk’s early photographs from the ’50s and Jerome Caja’s irony-infused paintings, created with Day-Glo colors as he was dying from AIDS in the ’90s. Greer Lankton’s tawdry sculptural dolls offer a vision of East Village New York during the ’80s.

— John R. Killacky

Maria Callas would have turned 100 on December 2, 2023. In honor of her centennial, Sophia Lambton has published a 500-page biography, The Callas Imprint (published by The Crepusular Press), whose bibliography, notes, and index swell the page count to 644. But there’s no padding in this deeply researched book. It surveys what feels like every twist and turn in the great operatic soprano’s life and career.

Maria Callas would have turned 100 on December 2, 2023. In honor of her centennial, Sophia Lambton has published a 500-page biography, The Callas Imprint (published by The Crepusular Press), whose bibliography, notes, and index swell the page count to 644. But there’s no padding in this deeply researched book. It surveys what feels like every twist and turn in the great operatic soprano’s life and career.

Callas, the author argues, has too often been lambasted and caricatured. Over the course of 12 years, Lambton conducted interviews with individuals who worked with Callas and has explored little-touched archives, enabling her to quote, for example, correspondence between Callas and her manager, Sander Gorlinsky.

Lambton is at her strongest when describing the details of Callas’s many recordings. Here’s her carefully detailed observation about Callas’s 1957 studio recording of Cherubini’s Medea. “What Maria wanted to achieve in this Medea was the portrait of a Machiavellian witch…. Plangently stressing the syllable ‘PLOR’ in ‘Imploro, mio signor’ (‘I beg you, sir’) is a bloodthirsty poser pretending to be a mere mother who fears for her children… The command ‘Dei figli miei l’amor mi rendi’ (‘Return to me the love of my children’) is fraught with excessive vibrato, charging a soul simultaneously desperate and ominous. The listener remains oblivious to whether she is earnestly or spuriously tender. And it should be that way”

Callas’s recordings continue to be rereleased (see Jon Garelick’s insightful review of the recent Warner boxed set: 131 CDs, 3 Blu-rays, and a DVD-ROM), and for the best of reasons: this singer possessed a searing intensity of vocal production and a keen insight into character that is always cherishable in the opera world. And sometimes (though, of course, not always) in recordings made in the middle and end of her career, she managed to turn her accumulating vocal defects into tools of authentic artistic expression.

— Ralph P. Locke

Mesmerized by the mysteries and contradictions of the contemporary art world to the point that she could not look away, Bianca Bosker set off on a quest to probe the expansively enigmatic heart of New York’s visual arts scene. For several intense years, the award-winning journalist (the Atlantic) and author (NY Times best-selling Cork Dork) immersed herself in the city’s highly layered, perpetually evolving, furiously creative, ever-marketing, -selling, and -collecting arts world.

Mesmerized by the mysteries and contradictions of the contemporary art world to the point that she could not look away, Bianca Bosker set off on a quest to probe the expansively enigmatic heart of New York’s visual arts scene. For several intense years, the award-winning journalist (the Atlantic) and author (NY Times best-selling Cork Dork) immersed herself in the city’s highly layered, perpetually evolving, furiously creative, ever-marketing, -selling, and -collecting arts world.

In Get the Picture (Viking, 384 pages), Bosker entertainingly tells the story of how she became involved in New York’s gallery scene, as a gallery helper, an artist’s assistant, and a museum guard. Her journey takes her into the purview of gallerists, collectors, curators, artists themselves, and even into arts fairs. The lower rung of gallerists and artists survive by multitasking, often working at multiple jobs (artist/carpenter, artist/teacher, artist/salesperson, etc). That is the price to be paid in order to afford the rent for studios or to maintain fledgling galleries. Hustling — driven by obsession — is rampant.

Glorious descriptions are leavened throughout the book: “Miami was heaving with art. It dangled off buildings and sunned itself on the beach.” And “Even if an artwork affects you so deeply it makes you decide to quit your job and, say, run off to Tuscany to become a puppeteer, the proper response is to arch your eyebrow and say Hmmm.”

Bosker also offers a key to the ambiguous and sometimes confounding artspeak known only to the most in-the-know gallerists and collectors. Example of the parlance: “an artwork is not sold but placed.” Along the way, she probes the cogs and gears of the art-canonization machine. She talks to wealthy collectors, investigates prominent museum collections (the art world’s Holy Grail), and goes into the class/caste system that aids and abets the process. She deals with some people who are not very nice to her, but the author is generous to all. One or two, after reading the book, may call Bosker “the enemy,” even a pariah, given how truthfully she takes the role of the journalist. This is a book that ranges widely but knowledgeably, jumping from cave paintings to the Renaissance, checking out Instagram as well as the science of sight and the psychology of beauty. Throughout, Get the Picture is never less than a witty read, an entertaining examination of visual art’s less known role in maintaining culture, the economy, and even our sense of well-being.

— Mark Favermann

Éric Chevillard is a virtuoso of the short form. He has written almost two dozen novels — all slender — including the masterfully delirious Prehistoric Times, yet his favored medium is the subversively illuminating anecdote. Since 2007 he has religiously, if not compulsively, maintained a three-entry a day habit on his blog L’Autofictif, the source of the texts in Museum Visits (translated from the French by Daniel Levin Becker with a foreword by Daniel Medin. Yale University Press, Margellos). In them and with a flourish, Chevillard pulls the metaphysical rug out from under us. A slight shift in perspective or a deft extensio ad absurdam and the solid footing we so blithely take for granted crumbles.

His narrators and protagonists, obsessive and slightly off-kilter, visit museums for the particular sound of the floorboards or exclusively for the frames or the works of minor masters such as Brueghel the Vague Cousin or Bläser the Elder. They throw moles and other projectiles into Samuel Beckett’s garden or, despite their suspicion of chairs, turn their backs on them only to be broken in three.

Most of the pieces are narrated in the first person and these, in particular, reveal Chevillard to be a Montaigne for our attention-challenged age. Montaigne elevated the portrayal of the inconsistent self into an art form. “Whoever studies himself attentively finds in himself — yes, even in his judgment — this mutability and discordance,” he observed. Chevillard takes up Montaigne’s mantle and peers through its fraying seams.

To date, Chevillard has been extremely well served by his English-language translators. Daniel Levin Becker extends this successful run with flair, effortlessly recreating the writer’s deadpan exhilaration, antic severity, and mercurial consistency. In this kaleidoscope of absurdities, indulgent glimpses of others’ foibles come perilously close to reflections of our own inner lives.

— Tess Lewis

“The effect of this climate on the soul is not to be underestimated,” wrote Samuel Beckett in his prose piece “The Lost Ones.” As the effects of the pandemic linger and the climate crisis escalates — the New York Times recently reported about panic of scientists at an alarming rise in ocean temperatures — an artist who excelled at registering the soul’s calibrations under the pressure of devastation has come into his prophetic own. Critic Gabriele Schwab in Moments For Nothing: Samuel Beckett and the End Times (Columbia University Press, 273 pages) argues that, in their perpetually losing battles with emptiness, Beckett’s absurdist figures may well be “precursors of a nightmarish future to come.”

“The effect of this climate on the soul is not to be underestimated,” wrote Samuel Beckett in his prose piece “The Lost Ones.” As the effects of the pandemic linger and the climate crisis escalates — the New York Times recently reported about panic of scientists at an alarming rise in ocean temperatures — an artist who excelled at registering the soul’s calibrations under the pressure of devastation has come into his prophetic own. Critic Gabriele Schwab in Moments For Nothing: Samuel Beckett and the End Times (Columbia University Press, 273 pages) argues that, in their perpetually losing battles with emptiness, Beckett’s absurdist figures may well be “precursors of a nightmarish future to come.”

This penetrating study connects Beckett’s gaunt visions of loss with our “era of ecological crises, mass extinctions, the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene.” At times drawing on memoir and personal trauma, Schwab explores how the dramas Happy Days and Endgame, as well as major prose works such as Molloy and The Unnamable, aggregate “new possible referential horizons in accordance with changing times.” The causes of the hellish experiences of dissipation that afflict his figures — internally and externally — are ambiguous [the author excised a reference to the atomic bomb in Happy Days]. Because Beckett’s works are “driven by using extrapolated memories of catastrophes and cataclysms to propel the imagined worlds of his characters,” their apocalyptic inspirations are presciently free-floating.

In a terrific chapter on Happy Days, Schwab quotes novelist Richard Powers: “It won’t be our capacity for despair that does the race in; we are damned by how easily we shrug the darkness off.” Beckett poetically deconstructs the ways we try to shrug off darkness; he is fascinated (perhaps even moved) by just how unsuccessful we are. “Happiness is but a more bearable form of suffering,” comments Schwab. Her explorations of Beckett’s dramas are particularly astute; a revelatory coda sees his 35-second play “Breath” as a work of “pandemic surrealism.” Be warned: the chapters on the prose works can be heavy going, filled with abstract bows to the French theorists.

— Bill Marx

Popular Music

Audra McDonald at Symphony Hall. Photo: Robert Torres/Celebrity Series of Boston

Is there a vocalist more lovable than Audra McDonald? This sublime, lavishly gifted singer-actress kept her besotted audience spellbound on Tuesday at Symphony Hall via a thrilling evening of song and inspiration. Many in the audience were longtime Audra devotees, such as a singer friend who reminded me before the show, “Make sure you use all your superlatives!”

“I know I’m four months late,” McDonald said early on. (She was originally scheduled for this Celebrity Series appearance in November). “I’m sick tonight too, so we’ll see what comes out.” No worries — she was sensational. McDonald arrived with her regular longtime backup ensemble: Glenn Zaleski, piano; Mark Vanderpoel, bass; and Gene Lewinn, drums. A pick-up orchestra provided admirable support. Her selections came mostly from the Great American Songbook, with a detour by way of a tune made famous by Sesame Street, “It’s Not Easy Being Green,” a favorite song from her childhood that addressed the feeling of being “othered.

Other offerings were mainly standards. The docket included a British-accented rendition of “I Could Have Danced All Night” from My Fair Lady (the singer insists the audience members join in with her — with a British accent!), “Cornet Man” from Funny Girl, Duke Ellington’s “Don’t Mean a Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing,” “I Always Say Hello to a Flower” by Murray Grant (a songwriter and singer in the ’40s who eventually opened a pet store), Jerry Herman’s “Before the Parade Passes By” from Hello Dolly, and “I Am What I Am” from La Cage Aux Folles. Her version of “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess still packs amazing power. Her top notes are all there; no one embodies or puts this song across better. McDonald joked, “If you don’t know this one I can’t help you.”

— Susan Miron

Film

A scene from S. Leo Chiang’s Oscar-nominated documentary short Island in Between.

One might expect short films to show some daring in subject and style. Isn’t that one of the purposes of the form? But this year’s Oscar Nominated Documentary Shorts (at the Coolidge Corner Theatre) play it safe for the most part. This is in contrast to those in the feature category, a lineup that boasts the immediacy and urgency of 20 Days in Mariupol, the formal inventiveness of Four Daughters, and the rigor of To Kill a Tiger. Instead, with one exception, the shorts category presents anodyne topics with tepid competence.

Such is the case with Sheila Nevins’s The ABC’s of Book Banning, which is as rote as the title suggests. Who is the audience for this film? It will not sway any who disagree, nor those who aren’t sure whether banning books for schoolchildren is a good idea. Even those sympathetic with its arguments will find it pedantic.

John Hoffman and Christine Turner’s The Barber of Little Rock promotes the initiative of Arlo Washington, the title entrepreneur, to assist other Black business owners to succeed. A worthy cause but an uninspired infomercial.

More ambitious is Ben Proudfoot and Kris Bowers’s The Last Repair Shop, which is about a Los Angeles program that repairs musical instruments for underprivileged children in the public school system. The craftsmen who work there tell their own stories – they too were underprivileged children with tough histories for whom music proved essential. A clever if pat device promoting a beleaguered program.

Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó are the names of filmmaker Sean Wang’s grandmothers. They live together and are old. Sean visits them and they get goofy — dressing up, dancing, and talking about farts. Moral: old people are funny and kind of sad and Sean should visit more often.

One image alone in S. Leo Chiang’s Island in Between surpasses all the other shorts in its cinematic brilliance: a derelict tank buried in the sand on the beach of Kinmen, a tiny Taiwanese possession. A tilt of the camera reveals a towering cityscape in mainland China just offshore. This taut but dreamy 20-minute memoir and meditation is a concise introduction to the traumatic history of Chiang’s homeland (you might also want to check out the Edward Yang retrospective at the Harvard Film Archive.)

–Peter Keough

Anthony Hopkins in One Life.

In the winter of 1938, a young London stockbroker named Nicholas Winton was planning to spend his Christmas vacation skiing in Switzerland. But his good friend Martin Blake, a member of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia, telephoned from Prague and asked him to come there instead. Like his better known contemporary American journalist Varian Fry, Winton threw himself into helping thousands of people trapped in Nazi-occupied Europe get papers, get British sponsors, and get out -– only in his case the people were all children.

One Life, directed by James Hawes, based on If It’s Not Impossible…The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton by Barbara Winton, is not the first film about Winton nor about the kindertransports. But it is by far the most meticulously documented, beautifully produced, and brilliantly acted. The stellar cast includes Anthony Hopkins as a convincing older Nicholas Winton looking back over his wartime past; Johnny Flynn as the young, naïve stockbroker, energetically backed up by his grandiosely fierce mother Babette, played by Helena Bonham Carter. They are supported by an extraordinary cast of British and Czech actors, including Lena Olin, Romola Garai, Alex Sharp, and Jonathan Pryce, who filmed in London and Prague. Many of the extras in the film are children of the 669 children saved by Winton and the BCRC.

One Life moves between the late ’80s, when Winton and his wife Grete are in their 70s and expecting to become grandparents, and 50 years earlier. Giving in to her wish to declutter their suburban house before the new baby arrives, Winton pores over old papers and photographs, talking with his old friend Martin and trying to figure out whether to donate them to an archive, library or museum. But the real drama of the movie takes place in Prague where we meet The Committee’s courageous and energetic director Doreen Warriner (Romola Garai) and her largely female staff, and view a series of parents and community leaders grapple with the decision of trusting a total stranger with their often very young children’s lives.

This is a film about an ordinary man moved to extraordinary action, without much psychologizing or melodrama. For people who know the story, it’s rewarding to see it so movingly brought to life; for those who don’t, it will be a revelation. U.S. release date: March 14.

— Helen Epstein

Visual Art

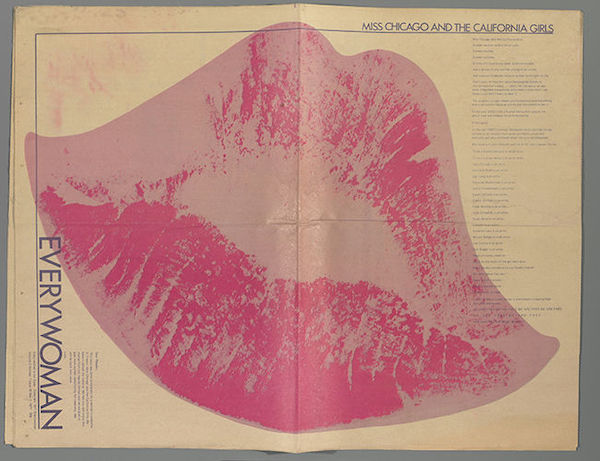

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, EVERYWOMAN, May 7, 1971. Offset lithographs on newsprint. Courtesy Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

There is a shocking line in the biography of graphic artist, activist, and design educator Sheila Levrant de Bretteville: in 1990, at the age of 50, she became the first woman to be tenured at her alma mater, the Yale School of Art (founded 1869). Given the lateness of that moment, it seems appropriate that much of de Bretteville’s career was involved with developing feminist design, establishing programs to train women in art, and collaborating with other feminist artists.

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville: Community, Activism, and Design, an exhibition at the Yale Art Gallery, traces de Bretteville’s career after her Yale graduation in 1964. It begins with handsome early commissions for prestigious clients like Yale University Press, Olivetti, and the American Institute of Graphic Artists. During the 1970s and ’80s, after she moved to Los Angeles to teach at CalArts, the scale grows to encompass architectural-sized collaborations with community groups and in scope to include projects with activist artists like Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. The Women’s Building in downtown L.A. was another collaboration, which sought to establish a public center for women’s culture.

Throughout it all, the exhibition suggests, de Bretteville continued to work in the classic modernist graphic style that ultimately goes back to the Bauhaus: streamlined sans serif typefaces, ample, elegantly arranged negative space, and a minimalist aesthetic that still feels contemporary. It was a very different approach from the scruffy, long-haired protest graphics of the ’60s, with their bold, brightly colored shapes and handwritten messages, often hastily silkscreened the night before an antiwar march — a style Corita Kent elevated to high art. An exception is de Bretteville’s Pink (1974), a collage of handwritten notes and photographs and a meditation on the color’s many stereotypes.

— Peter Walsh

Television

A scene from Detective Forst. Photo: Netflix

Detective Forst, an Eastern European crime thriller series on Netflix, is taut and sleek. The series balances darkly disturbing visuals with character-driven suspense.

Boris Szyc (known for Pawel Pawlikoski’s Cold War) is Commissioner Wiktor Forst, a complex, deeply flawed, yet brilliant police detective whose recent professional indiscretions find him banished to work in his hometown in the highlands of Poland. His personal life is a mess and his tendency to get romantically involved with women he shouldn’t is evident from the get-go. Despite his impressive record for solving homicides, Forst, in the mold of other fictional detectives we’ve come to know and love, doesn’t play well with others.

As he begins work on a baffling and high-profile murder case, he’s fired for insubordination by his boss, Chief Inspector Edmund Osica (Andrzej Bienias), who knows Forst is involved with his unstable daughter. In addition, Edmund may be in league with Dominika (Kamilla Baar), the brusque district attorney who wants to keep Forst out of the spotlight. Meanwhile, the detective is on fire with ideas for solving the murder and he teams up with Olga (Zuzanna Saporznikow), a daring but reckless photojournalist who has also bungled her career indulging in the same sort of fiery rebel antics as Forst.

A match made in heaven, perhaps, but they keep each other at arms’ length for the sake of solving the crime, at least at first. The darkly romantic mountain setting pairs well with the gritty, often brutal murder scenes left by an elusive psychotic killer. Forst is obsessed with finding whodunit, but finds himself in danger as he navigates a decadent criminal underworld. Featuring an impressive array of artistic and technical talent, Detective Forst is a world class production on every level, from design to performance. Stunning cinematography, a sweeping score, and edgy energy make this a very watchable series. But it is more than that; the acting and writing elevate the proceedings to the sublime. Steeped in human pain and pathos, Detective Forst is a first-rate crime drama that wields a deeply humanistic touch.

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: About Face: Stonewall, And New Queer Art, Anthony Hopkins, Audra McDonald, Bill-Marx, Detective Forst, Éric Chevillard, Gabriele Schwab, John R. Killacky, Maria Callas, Mark Favermann, Moments For Nothing: Samuel Beckett and the End Times, Museums Visits, One Life, Peg Aloi, Revolt, samuel-beckett, Sophia Lambton, Susan Miron, Tess Lewis