Book Review: “Witness: An Insider’s Narrative of the Carceral State” — A Voice Worth Heeding

By Bill Littlefield

Lyle C. May reminds us that large numbers of men sentenced to death have been exonerated, and that at every level the apparatus of the carceral state is erratic at best and dramatically biased against minorities and the poor.

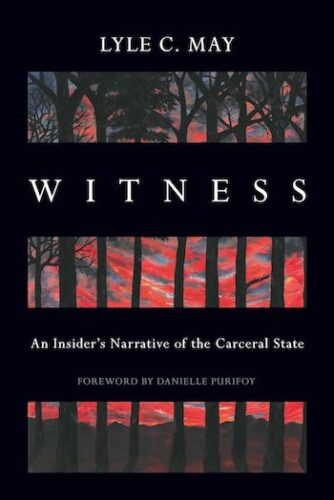

Witness: An Insider’s Narrative of the Carceral State by Lyle C. May. Haymarket Books, 282 pages, (paperback) $19.95.

Nobody is more qualified to convey the grim and dehumanizing aspects of incarceration in North Carolina than Lyle C. May, who was sentenced to death in 1999 at the age of 21 and for decades has lived there on death row. He has maintained for nearly 25 years that he did not commit the crime for which he was sentenced.

Nobody is more qualified to convey the grim and dehumanizing aspects of incarceration in North Carolina than Lyle C. May, who was sentenced to death in 1999 at the age of 21 and for decades has lived there on death row. He has maintained for nearly 25 years that he did not commit the crime for which he was sentenced.

Against ferocious odds, May has managed to gain access to college courses and various outlets that have published his writing. Like any good writer, he recognizes the value of a striking story. Some of his narratives are likely to surprise even people familiar with how twisted and cruel life can be for folks who are incarcerated. In the chapter of Witness titled “On Death Row, Eating to Live,” he takes a close look at the matter of the “last meal,” not from the condemned man’s perspective, but the point of view of the correctional officers who’ll march that man to his death or watch him walk by. About “the party” the guards customarily had on the night before each execution, May writes, “the most galling part was the sheet cake.”

“Usually, there would be a half dozen two-liter bottles of soda, oversized family bags of chips, dips, cheeses, crackers, jars of cocktail sausages, trays of cookies, and that enormous sheet cake covered in colorful swirls of frosting.…Wide-eyed and with barely concealed smiles, prison staff would deny that this was a celebration of any kind. Their denials were clearly lies, always delivered lightly with a guilty child’s ‘who me?’ impudence.”

May argues powerfully for the abolition of capital punishment and the life-without-parole sentence. He reminds us that large numbers of men sentenced to death have been exonerated, and insists that on every level the apparatus of the carceral state is erratic at best and dramatically biased against minorities and the poor. May presents statistics that prove that harsh sentences, capital punishment included, don’t deter potential felons. He demonstrates through his own growth — and accounts of many of the men he’s known in prison — that people mature and change. This is an especially powerful argument with regard to men who were arrested and incarcerated as juveniles; as May and others have repeatedly pointed out, studies of the brain have established that young males are particularly prone to act impulsively. When those young men are Black, they are especially likely to be arrested and entered into “the system” — even if the impulsive act is relatively minor. Admittance into “the system” often means the next impulsive act will be treated much more seriously. But should those young men be incarcerated into their 50s or 60s or until they die? May doesn’t think so, and May’s arguments are compelling.

One of the most powerful chapters in Witness is titled “Executing Illness: Punitive Responses to PTSD and Other Psychological Injuries from War.” Politicians are unlikely to pass up an opportunity to celebrate the troops; the public gathers on various occasions to celebrate the contributions and sacrifices of our men and women in uniform … or most of them. But, as May sardonically underlines:

“When violent crimes are committed as a direct result of the trauma experienced by combat veterans, the criminal justice system is unsympathetic. Retribution replaces mercy, and “Thank you for your service” becomes a meaningless platitude cast among the spent shells of a silent war.”

May has found that “approximately 15 percent of prisoners incarcerated for homicide are military veterans” and “22 of the 139 prisoners on North Carolina’s death row are vets.”

Of course PTSD is not the only mental health condition that afflicts many of the men and women who’ve been incarcerated, some of them for decades, some of them until they die. As May and others have established, “over half of all prisoners have experienced some form of mental illness, like depressive episodes or addiction, while at least 20 percent suffer from a serious psychological disorder and lack access to adequate mental healthcare in prison.” Failure to provide adequate psychological care is only one of the many examples of “cruel and unusual punishment” May chronicles in the prisons of North Carolina. There’s no reason to believe his experience there is not, at least to some extent, representative.

May argues in his chapter “Reform or Abolish” that reformers, some of them no doubt well meaning, created the penitentiary in the first place, going on to assert that “reforming a flawed system does nothing to address the flaw.” Prison “has always been an instrument of classist oppression and torture…. Many have tinkered with the edges of mass incarceration, but that is all.”

Lyle C. May. Photo: Prison Writers

But May is realistic enough to recognize abolishing prison is not likely to occur overnight. He posits some progressive steps that could lead toward that desired end. He starts with the abolition of the death penalty. He suggests that “’a second-look mechanism’ could be established to review life, virtual life, and life without parole sentences of prisoners who have served a minimum of twenty-five years.”

May would also like to see the elimination of immunity for prosecutors, many of whom cannot be held accountable for abusing their power, an entitlement that leads to wrongful prosecutions, the forceful extraction of guilty pleas from innocent defendants, and false imprisonment.

Perhaps May’s most creative suggestion is that prison officials should be “held accountable for recidivism in their state.” The idea is that a man’s failure to stay out of prison represents the failure of the authorities; it might primarily be the fault of prison officials or parole officers to provide the formerly incarcerated person with the means to survive in the world outside.

Lyle May is a tempered writer; he’s wise enough to trust the power in his message and to avoid overstating it. He deserves enormous respect and credit — not only for what he has already committed to paper, but for the fact that he has written at all. As May points out, incarcerated activists are not popular among those who are charged with confining them. It’s not surprising that May is no stranger to solitary confinement.

Bill Littlefield volunteers with the Emerson Prison Initiative, a program that enables incarcerated men to pursue a college degree. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing).

From Dudley Sharp, independent researcher, death penalty expert. CV at link provided above. I have edited out footnote links …

It’s impossible to know if May is being dishonest or is, just, willfully ignorant, refusing to fact check and vet, as Littlefield.

These rebut all of Littlefield’s and May’s points, as discussed in the referenced.

1) Depending upon review, the anti-death penalty groups claims of “innocent”/”exoneration” from death row are 71-83% fraudulent, with 99.6% of death row convictions being factually guilty, with the 0.4% factually innocent being released, likely the most accurate of any sanction. (1). Known since 1998.

2) Constant deception. Another false innocence claim.

It is repulsive that Littlefield wrote: “(May) has maintained for nearly twenty-five years that he did not commit the crime for which he was sentenced.”

Littlefield cared not about the truth nor the two innocent murder victims. How do we know? He would have looked up the case (2). I presume he did not. Ask him.

May confessed, both orally and in writing, to the murders of Valerie Sue Riddle, 24, and her four year old son Mark Laird Jr., by stabbing and beating them to death. May’s clothes were covered with their blood (2).

“In addition to an oral confession, defendant gave a confession in his own handwriting. In that written statement, he confessed that he had stabbed Valeri Riddle to death because she “got on [his and Godfrey’s] nerves.” He also wrote that he had killed Mark Laird because he “did not want to see the kid crying or having the memory of his mom getting killed.” He then described how he had disposed of the bodies and how Godfrey had “watched both killings and went along willingly for the ride.” (2).

All the evidence, as Godfrey and May, confirmed May’s guilt (2).

“The autopsy report showed that Valeri Riddle had been stabbed multiple times. She had suffered blunt-force injuries that fractured her skull, and her neck had been broken. Mark Laird had been stabbed and beaten.His blunt-force injuries were likely made by a heavy, cylindrical object like a pipe or baseball bat.” (2).

Littlefield and May prove the constant and the obvious, anti-death penalty folks care much more about guilty murderers than about their innocent victims (3), as Littlefield demonstrated.

The innocence lies are not repulsive, simply, because they are a lie, but that the lie includes their innocent murder victim and their survivors, who the liar wants to harm, even more and Littlefiield helped.

Does Littlefield care? Very much, That is why he did not research, not fact check and not vet. He cared about the guilty murderer, not his innocent victims (3), an anti-death penalty norms (3).

2) White murderers are twice as likely to be executed as are black murderers. From 1977-2012, white death row murderers have been executed at a rate 41% higher than are black death row murderers, 19.3% vs 13.7%, respectively.”There is no race of the offender / victim effect at either the decision to advance a case to penalty hearing or the decision to sentence a defendant to death given a penalty hearing.” For the White–Black comparisons, the Black level is 12.7 times greater than the White level for homicide, 15.6 times greater for robbery, 6.7 times greater for rape, and 4.5 times greater for aggravated assault. As robbery/murder and rape/murder are, by far, the most common death penalty eligible murders, the multiples will be even greater, as one would expect. (4)

3) “99.8% of poor murderers have avoided execution. It is, solely, dependent upon one’s definitions of “wealthy” and “poor”, as to whether “wealthy” murderers are any more or less likely than 0.2% to be executed, than are the “poor”, based upon the vast minority of capital murders committed by the “wealthy”, as compared to the vast majority committed by the “poor”. By far, the greatest number of capital murder cases are robbery/murders, with nearly 0% of “wealthy” capital/death penalty eligible murders committed by the “wealthy”, based upon any reasonable definition of wealthy. Obvious. (5)

4) The death penalty/executions protects innocents , in four ways, better than does a life sentence, inclusive of deterrence, which has never been negated and cannot be, as known for millennia, with 24 US based death penalty/execution studies finding for deterrence, studies which are more credible than their detractors (6),

with

Nobel Prize Laureate (Economics) Gary Becker:

“the evidence of a variety of types — not simply the quantitative evidence — has been enough to convince me that capital punishment does deter and is worth using for the worst sorts of offenses.” (NY Times, 11/18/07)

“(Becker) is the most important social scientist in the past 50 years (NY Times, 5/5/14)

In Closing

Littlefield, is anything in May’s book true? How would you know?

Dear Mr. Sharp,

An Op-Ed journalist is an oxymoron. Since anyone can have an opinion and get published in the newspaper, for his belligerence or blood lust overseeing another human being exterminated, then travel the media circuit claiming how much he supports State-sanctioned murder, maybe the bigger problem with espousing your beliefs about the criminal legal system Mr. Sharp, isn’t that you do, it’s that there will always be people out there who don’t know enough about our laws and will believe everything you tell them. Whether it’s Oprah or Bill O’Reilly, FOX News or ABC. Because you know as well as any that to make the news it has never been about the truth, just access to the right people. I know a fair number of death penalty experts, I also know an even larger number of people who have been put to death.

Opining on capital punishment from the outside is easy. You can do your “independent research” and sell it to the highest bidder and there will be buyers. But at the end of the day your opinions are empty, not because you lack the knowledge or statistics, rather, your advocacy and status should be used to help people. You can’t do that, support the death of another in the process, and maintain a valid argument.

Finally, Mr. Sharp, if you really want to know about my wrongful conviction, I direct you to my attorney, Jonathan Broun.

I’ll let him determine if you’re worth the time. (Jbroun@ncpls.org).

Sincerely,

Lyle C. May

I did not say in the review that Mr. May was not guilty. I said he had been maintaining for years that he was not guilty.

Whether or not he did was he was charged with doing, is he the same man twenty five years later? Having worked with incarcerated men for the past several years, I think that’s a question worth asking.

But Mr. May’s book is about conditions in the prisons where he has served time, and, more specifically, conditions on death row, not about what he did or did not do to get incarcerated.

There are all sorts of statistics regarding whether capital punishment deters anybody. I have not seen conclusive evidence that it does. Organizations like The Innocence Project have demonstrated that many incarcerated men and women have confessed and taken plea deals out of desperation, and that many incarcerated men and women have been misidentified or otherwise unjustly handled by the system. The numbers vary from place to place. There is no question that people of color are incarcerated in numbers far beyond their numbers in the population in general.

But as I said, for me the central point of Mr. May’s book is his account of conditions in the prisons where he has been incarcerated. Mr. Sharp does not argue that Mr. May is not qualified to describe those conditions accurately.

Thank you, Mr. Sharp, for reminding us of the innocent lives that May took in cold blood. The voice of evil has nothing to offer, and there is no reason to listen to this killer.

I sincerely hope this murderer is not profiting from this book, as that would only further insult the memories of the victims.

The article mentioned, from the Asheville Citizen-Times, highlights Lyle May’s story: https://www.newspapers.com/article/asheville-citizen-times-lyle-may/41221636/

It’s a mockery to say “Against ferocious odds, May gained access to college courses.” Inmates always receive various perks while incarcerated.

It’s appalling that my son’s murderer is now a minister in prison, he got to take a course. The justice system, because of criminal lovers, seems to prioritize the well-being of criminals over the rights of victims and the safety of society.

I’m sure Valerie and her young son would be comforted knowing that their killer is enduring such hardships.