Book Review: “Breslin: Essential Writings” — Compulsive Reading

By David Daniel

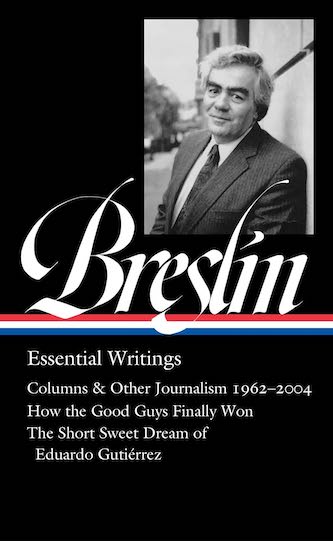

Breslin: Essential Writings, edited by Dan Barry. The Library of America, 723 pages, $40.

The notion that columnists like Breslin were “deadline artists” is apt. Their task was to come up with a story idea, track it down, then give it a narrative spark, all ahead of a ticking clock as the drop-deadline for the next edition loomed.

In the late ’60s, as his comic crime novel The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight was about to be published, the movie rights already sold, Jimmy Breslin announced that he was giving up the newspaper column he’d been writing three or four times weekly for many years, first in the New York Herald Tribune and then the New York Post. He was tired of seeing his “stuff” on the subway floor, he said. It was a good Breslin exit line; but the breakaway didn’t last. Having people’s feet on his “stuff” also meant their eyes were on it, too. In those days a large New York City paper could have two million daily readers, and a million more on Sunday. With his name recognition, Breslin helped drive those numbers. After time away for other projects, he joined the staff of the Daily News, where he stayed for many years.

In the late ’60s, as his comic crime novel The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight was about to be published, the movie rights already sold, Jimmy Breslin announced that he was giving up the newspaper column he’d been writing three or four times weekly for many years, first in the New York Herald Tribune and then the New York Post. He was tired of seeing his “stuff” on the subway floor, he said. It was a good Breslin exit line; but the breakaway didn’t last. Having people’s feet on his “stuff” also meant their eyes were on it, too. In those days a large New York City paper could have two million daily readers, and a million more on Sunday. With his name recognition, Breslin helped drive those numbers. After time away for other projects, he joined the staff of the Daily News, where he stayed for many years.

Now, the Library of America has brought out a generous selection of his writing — some 700 pages of Breslin in his various modes, including two book-length works and a wide-ranging assortment of his columns, selected by New York Times editor and columnist Dan Barry.

Widely regarded as the best in the game when it came to telling, with an unflinching eye, stories of urban life in Manhattan and its environs, Breslin was a New York guy in full. He was born in Queens in 1928. When Breslin was six, his father did a “paternal fade” — he stepped out for an errand and gone, smoke. At 10, he found his mother holding a pistol to her head. He wrestled it away and the incident was never spoken of again. In high school he played football, boxed a little, and began his career in journalism as a copy boy.

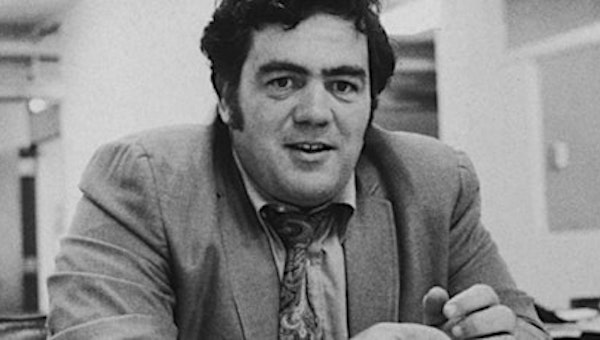

Fast forward to the heavyset, cigar chomping, F-bombing character out of Damon Runyon that he became in the postwar years. For him, writing a newspaper column was a contact sport. Given his messy dark hair and tie draped around his neck like a striped snake, Breslin was never going be mistaken for Pete Hamill, his suave contemporary and only legitimate challenger to Breslin’s journalistic primacy. He never learned to drive, so his method was to walk around and talk to people, take notes, cogitate, and then write to make deadline, which he never missed. He could be bellicose at times, even confrontational, but he always believed that a journalist has an obligation to readers and the community. And he possessed an indelible empathy for the common person.

Breslin’s reportorial spectrum was broad, and he had a knack for being on scene for big stories. He was present when Malcolm X was shot, and later, Bobby Kennedy. He filed dispatches from wherever history was being made: with people marching 50 miles from Selma to the steps of the capitol in Montgomery in troubled Alabama; Vietnam; England (when Churchill was in hospital dying); Ireland during the “Troubles”; the Mideast during more troubles. But there was never any doubt about his mastery of his home turf: no one felt NYC’s pulse more acutely. In columns covering Broadway Joe Namath, the closing of the Stork Club, the hunt for the “Son of Sam” serial killer, the AIDS epidemic, and the railroading of the Central Park Five, he stood back and let the events and people involved — always the people — speak for themselves.

The notion that columnists like Breslin — and Hamill, Mike Royko, and others — were “deadline artists” is apt. Their task was to come up with a story idea, track it down, then give it a narrative spark, all ahead of a ticking clock as the drop-deadline for the next edition loomed. On December 8, 1980, Breslin was home asleep when he got word that John Lennon had been shot. Hustling in from Queens, he sussed that the spotlight should be on the NYPD cops, who’d rushed the mortally wounded Lennon to the hospital. Two hours later, his column “Are You John Lennon?” was ready to hit the streets.

In November 1963, in the wake of the JFK assassination, Breslin’s story was about the ER surgeon at Parkland Memorial Hospital who attempted to save the President’s life. A few days later, in DC for the funeral, he didn’t follow the crowd; Breslin wrote about Clifton Pollard, the gravedigger at Arlington National Cemetery who dug JFK’s grave. Titled “It Was an Honor” (Pollard’s words when asked about his lonely task), it has become one of Breslin’s most celebrated pieces, used in journalism courses to make a point about avoiding the scrum of journalists and finding an angle. Try reading it without tears.

A sequence of columns from spring of 1985 begins innocuously enough: “At the start, it was over nothing, an alleged $10 sale of pot on a street corner in Queens, and now it has turned into a case that could change the system of law enforcement used in this city.” Breslin tells the disgraceful story of an 18-year-old Black man who is taken off a street corner one night by six white cops and hustled down to a precinct where he is electrically shocked multiple times. After being held incommunicado for hours, the man is finally arraigned. His mother, who hasn’t been told a thing, retains a lawyer, and the DA becomes involved. The medical examiner identifies the marks on the young man’s body as electrical burns of a kind that would have been made with a cattle prod. Breslin is on the story and the result is compulsive reading: his columns exposed a blatant instance of police brutality, concluding with a smackdown of the police commissioner, who stayed suspiciously absent during the events and ensuing uproar.

Jimmy Breslin at a New York City event for Mayor John Lindsay in 1970. Photo: Wiki Common

Most prescient is “Trump: The Master of the Steal,” a column from June 1990. By that point Trump was already perpetuating tax scams while he was making every effort to be in the news. The jukes and fakes that later became his faux Time magazine covers and “leaked” teasers about his wealth are already in full operation. Breslin, with a street-corner nose for stink, IDs The Donald as a publicity vamp voguing for an all-too-compliant media. According to Breslin, Trump survives by “Corum’s Law” (Bill Corum was a Hearst sportswriter who eventually became head of the Kentucky Derby after convincing Louisville businessmen that the folks attending the horse race expected to lose: “a sucker had to get screwed.”) This worship of bunkum is at the center of every Trump venture, though “instead of horseplayers, the suckers who must get screwed are a combination of news reporters and financial people.” The column concludes that Trump’s success is tied to his sticking to the rules his old man taught him: “Never use your own money. Steal a good idea and say it’s your own. Do anything to get publicity. Remember that everybody can be bought.” (Italics Breslin’s).

Breslin was unswayed by public opinion; if anything, he helped shape it. In contrast with the current media landscape wherein too often news seems meant to stoke (or stroke) partisans, he operated on the idea that one of the moorings of democracy is a free press. He respected a venerable apothegm: newspapers should comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. If he saw injustice, even if enacted by friends or people he admired, he called it out. A blue-collar Irish Catholic, his withering take on vainglory and corruption in the New York Archdiocese hit the institution like a grenade. When citizens began to mythologize subway vigilante Bernard Goetz as a hero, Breslin made a proposal worthy of Jonathan Swift — elect Goetz mayor.

Given the traumas of Breslin’s childhood, and later the deaths of his first wife and two grown daughters, the writer was no stranger to loss. He understood what it meant to be wounded. Politically a Democrat, he appealed to people of any ideological stripe because his work was embedded in the common experience. During the AIDs epidemic, when its sufferers were marginalized as “other,” Breslin put names and human faces to the patients and their families, humanizing them, breaking down the politically convenient “blame the victims” narrative.

Journalist Jimmy Breslin — he possessed an indelible empathy for the common person. Photo: Wiki Common

One of the recurring words in his columns is “yesterday” — literally “the day before.” It is a testament to how fresh his writing is — immediacy rises from it like the smell and smudge of ink off the newsprint. If Breslin brought heart and spine to his columns, he also brought humor, which could often be ironic. Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill emerges as a heroic figure in one of the volume’s book-length pieces, How the Good Guys Finally Won, which chronicles the dismantling of Nixon after Watergate. At one point, Breslin offers this tongue-in-cheek description of O’Neill: “At six-foot-two, and weighing anywhere from two hundred sixty-two pounds to two hundred eighty-two pounds, with a great nose, Tip is not trim enough, nor does he have the outward elegance to cause people to use Latinate words in describing him.” In another context, Rudy Giuliani is seen as “a small man looking for a balcony.” Breslin often turns his whip smart sarcasm on himself. Writing as he faces brain surgery: “I stared at the ceiling and kept seeing the faces of people I absolutely despise. I had promised the priest that I most certainly would stop my habit of slandering and backbiting…. But now here was all this temptation up on the ceiling. I said ‘Oh, lord, if you just let me call one of these people the name he deserves to be called, I will come out and build you a church.’” In 1986, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Commentary.

Recently, the Library of America hosted a webinar with Dan Barry, editor of the current volume, along with journalists Mike Barnicle and Mike Lupica. Young men when they first knew the older Breslin, they talked about how he inspired them. Barnicle, Boston’s closest journalist-kin to Breslin, puts it succinctly: “There was Jimmy Breslin and everyone else.” About Breslin’s approach to finding an entry to a story, all the participants agreed that he taught them that, by standing at the edge, you’ll pick up more. Everyone else will be crowded at the center.

The LOA volume supplies a detailed timeline of Breslin’s life, informative jacket flap copy, and a limited index. The book would benefit from a foreword that would put the journalist and his work into context; this would be of particular value to readers who are too young to know about Breslin. Still, that information is readily available elsewhere. Or forget elsewhere and get all you need from the source — the way Breslin did.

Long ago David Daniel was a columnist for the campus newspaper at the University of Maine, Orono. Drafted in 1969, he served as a military journalist. Later he wrote about books and jazz for the Patriot Ledger.

A tour de force review by Daniel about a muckraker for the ages. I had the distinct privilege of sharing an Army newsroom with Dave at the ARMORED SENTINEL, Ft. Hood, Texas. Once after I had offered up an especially lame piece on Bluebonnets Dave encouraged me to “Keep this good shit comin’,’ CRAWDADDY!

Now sixty years later we can revel in a review so informative that even Breslin himself would have admired it. Who else would have thought to expose us to JFK’s humble gravedigger but Daniel and, of course, Breslin.

I love Dave’s reviews often written while on hiatus from more serious literary undertakings. He has encyclopedic knowledge bolstered by careful research and backed up by a writer’s keen eye.

This review complies with his long ago admonition “ to keep the good shit comin’!” By the way, read you some Breslin!

What an incredibly well-written, informative, entertaining article.

Dave Daniel’s review would have been an excellent forward to the Essential Writings. It appears Daniel can do anything with prose: short stories, novels, flash fiction, and reviews. Now I have to go read Breslin’s “It Was an Honor.”

More Dave Daniel in The Arts Fuse!

Beautiful tribute!

This piece would have made a great foreword to the book: it makes me want to set everything aside and read Jimmy Breslin. I don’t think I’ve ever read anything by him. He was a contemporary of Charles Portis I see — the mention of Malcolm X made me think of the two writers’ different styles of contact sport. Portis’s fellow NY Herald Tribune reporter Tom Wolfe wrote about Malcolm X and Charles Portis appearing together on a Meet the Press type show. Before they went on, Malcolm X announced “he didn’t want to hear anybody calling him ‘Malcolm,’” so during the show “[t]he original laconic cutup, Portis, had invariably and continually addressed him as ‘Mr. X’… ‘Now, Mr. X, let me ask you this …’”

I can’t add much to the well-deserved praise above. About all I can offer is that the final line is especially good.

Dave Daniel says, “The book would benefit from a foreword that would put the journalist and his work into context.” This review does just that.

I loved both the juicy Breslin quotes and the wonderful flow of Daniel’s appreciative prose. What excellent journalism about a world-class journalist. I remember back when Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin ran for mayor and city council prez of NYC. The general feeling was that Breslin would’ve been a much better mayor than Mailer, who cursed out his audiences with profanity. “I found out I was running with Ezra Pound,” Breslin said, a reference to Pound’s madness, not his poetry. When Breslin was asked what he’d do if he won, he said “demand a recount.” The winner in that 1969 race was Republican liberal John Lindsay, derided as a lying hack back then, but now thought of as a prince of a pol from a better era. Luckily for his readers, Breslin stuck to writing after that!