Jazz Album Review: Kenny Barron’s “Beyond This Place” – As Enthralling as Ever

By Michael Ullman

The spirited restraint of the pianist’s playing — its omnipresent precision and clarity — sounds contemporary and fresh.

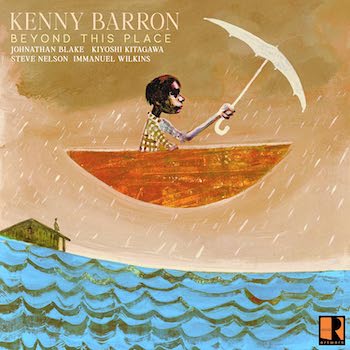

Kenny Barron, Beyond This Place (Artwork Records)

I first heard pianist Kenny Barron when I was in college in the mid-’60s. He played with Dizzy Gillespie at Kresge Auditorium at MIT. I was in my teens. He was born on June 9, 1943, just a couple of years older than me. He had an enormously productive post-adolescence. Before he was twenty, Barron had already recorded with his brother, the late Bill Barron, and also with Yusef Lateef, James Moody, and Dizzy Gillespie. Early on, he developed a range of skills. On Gillespie’s Something Old, Something New he plays uptempo bebop; the pianist goes a little further out on clarinetist Perry Robinson’ s Funk Dumpling, a favorite album of mine. Since Barron became old enough to vote, his career as a sideman and as a leader has proved to be unimaginably rich.

I first heard pianist Kenny Barron when I was in college in the mid-’60s. He played with Dizzy Gillespie at Kresge Auditorium at MIT. I was in my teens. He was born on June 9, 1943, just a couple of years older than me. He had an enormously productive post-adolescence. Before he was twenty, Barron had already recorded with his brother, the late Bill Barron, and also with Yusef Lateef, James Moody, and Dizzy Gillespie. Early on, he developed a range of skills. On Gillespie’s Something Old, Something New he plays uptempo bebop; the pianist goes a little further out on clarinetist Perry Robinson’ s Funk Dumpling, a favorite album of mine. Since Barron became old enough to vote, his career as a sideman and as a leader has proved to be unimaginably rich.

Saxophonists love him: besides Lateef, he’s on key recordings by Joe Henderson, Sonny Fortune, Marion Brown (Why Not), Charles Davis ,and, of course, Stan Getz, with whom he made the celebrated two-disc set of duets, People Time (Gitanes). He recorded “But Not for Me” with Chet Baker, “Django” with Jim Hall, “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” with Bea Benjamin, and “The Woody Woodpecker Song” with Woody Shaw. He accompanied Ella Fitzgerald on All That Jazz.

He was also the pianist for the group Sphere, which was dedicated to the compositions of Thelonious Monk, whose pieces appear everywhere in Barron’s discography: one of his albums is named Green Chimneys. The title cut is by Monk, and the trio with Buster Williams and Ben Riley also performs Monk’s “Straight, No Chaser” Kenny Barron had one hit, at least in terms of jazz radio: his tune “Sunshower,” which was the opening number on his album Innocence. He plays electric piano on that record, which was on the Wolf label — electric was the thing in 1978. He made an acoustic version on last year’s album, The Source (Arts Fuse review). What remains consistent throughout Barron’s career is the clarity of his ideas, the beauty of his sound, and his marvelous way of building tension and then letting it go. He effortlessly carries us along: his left hand skips or plays darting chords, or adds its own lines. Sometimes Barron infuses thumping Monk-like passages. On Ellington/Strayhorn’s “Daydreams,” he muses gracefully, his performance of the melody enriched — but not obscured — by his busy accompaniment.

Barron is celebrating his eightieth birthday with a new album, Beyond This Place, featuring in different combinations a quintet that includes saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins, vibraphonist Steve Nelson, bassist Kiyoshi Kitagawa, and drummer Johnathan Blake. He plays standards, a half dozen of his own compositions, and Monk’s “We See.” The set opens with a duet: the tenderest version of the standard “The Nearness of You” I know. The beauty of Barron’s touch is evident from the lulling intro. Then Wilkins enters quietly, adeptly infusing a vibrato while still playing at a whisper. The two are joined by the bass and drums that sets up an effective contrast. Musically, Barron is all about contrast. After the ballad comes an intense exercise between walking bass and drums; it’s the opening to the Monkish “Scratch,” a fast, bopp-ish tune filled with eccentric accents. Its melody features a lively repeated figure that stops suddenly. Barron finishes off the track with two staccato chords: I hear this ending as another tribute to Monk. As a soloist, Barron makes compelling use of a variety of rhythmic approaches.

The band pays more direct homage to Monk on “We See,” in which Barron scurrys downhill on the first bridge. “Innocence” was the title cut of Barron’s 1978 album. Here he handles the composition as sweetly as its title would imply. Still, note Blake’s deft, multifarious drumming. Wilkins’s solo is relaxed and lyrical. At first, he holds notes as if he wants to figure out how they taste, then he pushes the plate away to take up more energetic lines. Nelson’s vibes solo deepens the track’s texture. Barron takes care of his sidemen. Nelson is handed the first solo on the ballad “Sunset.” “Tragic Magic” is a tribute to another one of Barron’s piano heroes, Tommy Flanagan. Here the familiar “Softly as in a Morning Sunrise” zips along with cheerful vim: the pianist demonstrates his chops via long lines and some outré harmonic ventures.

The album’s title track opens as a duet between Barron and Wilkins. It sounds like an excursion into gospel to me. The spirited restraint of the pianist’s playing — its omnipresent precision and clarity — sounds contemporary and fresh. I get the feeling that Barron is what you would call a chameleonic pianist: he can sound anyway he wants. Barron’s had a career of over sixty years, and he continues to enthrall.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: "Beyond This Place", Artwork Records, Immanuel Wilkins, Johnathan Blake, Kenny Barron, Kiyoshi Kitagawa

Immanuel Wilkins sounds diffident throughout this album.