Film Review: “La Chimera” — A Celebration of Etruscan Grit and Glory

By Betsy Sherman

If La Chimera is a bit harder to penetrate than the director-writer’s previous works, it boasts some captivating passages and raises pertinent questions about art, history, globalism, and national identity.

La Chimera, written and directed by Alice Rohrwacher. In Italian with English subtitles. Screening at Coolidge Corner Theatre, Boston Common 19, Alamo Drafthouse Boston Seaport, and Landmark Kendall Square Cinema

Josh O’Connor in La Chimera. Photo: Ad Vitam Distribution

Italian director-writer Alice Rohrwacher has made a series of seductively playful films with a magical-realist sensibility and a distinctive aesthetic style forged in partnership with her French cinematographer Hélène Louvart. The pair started with the outstanding 2011 coming-of-age picture Heavenly Body, followed by The Wonders, Happy as Lazzaro, and the charming Oscar-nominated short Le pupille/The Pupils. Their new one, La Chimera, depicts a gritty rather than lyrical late-20th-century Tuscany as it recalls the glories of the region’s Etruscan past. It’s of a piece with Rohrwacher’s tales of provincial people living on a modest rung of the socioeconomic ladder: some plod along complacently, others stir things up with brio and creativity. If La Chimera is a bit harder to penetrate than the director-writer’s previous works, it boasts some captivating passages and raises pertinent questions about art, history, globalism, and national identity.

The movie is set in the 1980s. Its central character is a young Englishman named Arthur, played by Josh O’Connor (Prince Charles in seasons three and four of The Crown). In an enigmatic opening sequence, a shot of a young woman’s tattoo (depicting the sun) may be part of Arthur’s dream, or a memory. Arthur wakes up in a train compartment; he’s recently been released from jail. Scruffy in a rumpled cream-colored suit with flared pants, he has a few days’ beard. The conductor and a peddler mock Arthur, but the local young women around him are fascinated. He remarks on the large nose of one of them, and tells her to be proud of this gift from her Etruscan heritage.

Near the tin-roofed shanty in which Arthur lives sits one of the colorful domains of the story’s humor-tinged drama: the villa of Signora Flora (a wonderful Isabella Rossellini). Both the house and its owner have seen better days. Arthur is mourning the loss of his sweetheart, Flora’s daughter Beniamina. The distraught Flora refuses to accept that the girl is dead; she awaits Beniamina’s return. Meanwhile, she leans on Arthur for comfort; it’s a warm relationship. Flora is matriarch to a circle of red-haired daughters and granddaughters prone to gossiping. They’d like to put their mother in a nursing home and sell the crumbling villa.

Arthur rejoins a band of local grave-robbers, or tombaroli. They call him their maestro, and not only because of his scholarship in archaeology and history. He has sure instincts for finding Etruscan tombs. Arthur uses a divining rod to make contact with the life forces still pulsating under the ground. Wherever he faints, the gang knows that’s the spot to start digging. But the money he and his confederates glean from the illegal artifacts market isn’t Arthur’s goal. Nor is he after mere intellectual satisfaction. Arthur’s on a quest for the metaphysical dimension in which he can join Beniamina, a red-haired, delicate beauty whom we get glimpses of in solar-flare-pierced cut-in shots.

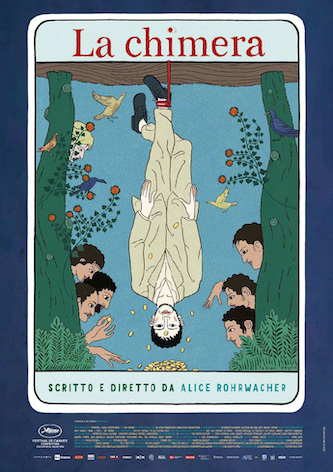

The Italian poster for La Chimera.

Arthur is too in love with the afterlife to find pleasure in this world. But there’s a secret weapon pointed at him, in a good way. Her name is Italia, and she’s exchanging work as a housekeeper for opera-singing lessons from Flora (too bad Italia is tone-deaf and a lousy maid). Endearingly played by Brazilian actress Carol Duarte, Italia is a goofball, and something of a conjuror; she has been hiding her two children from Signora Flora in the big old house. She enters Rohrwacher-land appropriately — in a hot pink parka. She and Arthur hit it off; the funniest scene in the movie is when Italia gives Arthur a crash course in Italian hand gestures. Appropriately, the words she teaches involve deception (“crafty,” “pilfer”). One summer night, she goes along with the gang to an open-air bash. But when she learns about the tomb-raiding, she’s shocked at the sacrilege (“Those things aren’t made for human eyes”). Late in the film, Italia reveals unexpected talents and a willingness to take risks.

Despite the presence of a rival gang, occasional police, and balladeers who enshrine Arthur and the tombaroli in song (The Adventures of Arthur the Dowser), one of the things La Chimera is not is a caper movie, This gang does not keep things on the down-low. For the Feast of Epiphany, they participate in the local tradition of dressing in sloppy drag as the Christmas Witch. Events lead to a showdown with the kingpin they’ve been selling their finds to, but had never met. This comes after they’ve discovered the remains of a remarkably well-preserved Etruscan temple (as in Fellini’s Roma, its frescoes fade once humans let air in). In here, Arthur feels such a strong connection, especially to a statue of a goddess, that it changes him.

Josh O’Connor does a superb job of maintaining a throughline among the story threads. With doleful eyes and droopy body language, he draws us into Arthur’s sadness and keeps us wanting to know more about the wandering Brit (who’s associated with the Hanged Man tarot card). Catch the actor in Luca Guadagnino’s upcoming Challengers — as a robust, rascally American tennis player — and you may not believe it’s the same person.

Rohrwacher, dedicated to filming on actual film, changes up the visual ambiance. The characters’ daytime lives were shot on Super 16, while the nighttime scenes and the underground haunts of the Etruscans were shot on 35mm. Louvart used a 16mm Bolex camera to film animals, nature, and some shots of Arthur. As is her practice, Rohrwacher breaks up an earth-tone palette with splashes of bright pink, turquoise, yellow, and the like, often in the costumes (actress sister Alba Rohrwacher wears a yellow ’80s power suit with shoulder pads, Beniamina a multicolored crocheted dress).

La Chimera celebrates the porousness of borders: between time periods, spiritual realms, and all living beings (one of the tombaroli says the Etruscans believed “the flight of birds could predict our destiny”). The film also posits the strength of connection: the tensile strength of a piece of red yarn can support a passage between states of consciousness.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Alba Rohrwacher, Alice Rohrwacher, Hélène Louvart, Josh O'Connor