Jazz Album Review: Abdullah Ibrahim’s “3” – Meditations on a Legacy

By Steve Elman

A new release from Abdullah Ibrahim adds almost 100 minutes to a legacy of paramount importance to jazz, to world music, and to our understanding of a life lived in art.

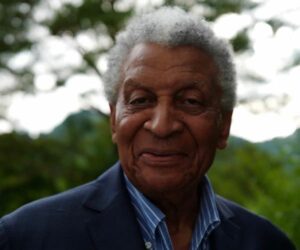

-Thumbnail.jpg) In 1960, when 25-year-old pianist Adolph Brand made his recording debut in Johannesburg, South Africa, his country was still in the grip of apartheid and he was a nobody in the world of jazz. When 89-year-old Abdullah Ibrahim played the Barbican Centre in London in the summer of 2023 with two of his bandmates from his group Ekaya, the 1900+ attendees gave him the kind of reception reserved for living masters.

In 1960, when 25-year-old pianist Adolph Brand made his recording debut in Johannesburg, South Africa, his country was still in the grip of apartheid and he was a nobody in the world of jazz. When 89-year-old Abdullah Ibrahim played the Barbican Centre in London in the summer of 2023 with two of his bandmates from his group Ekaya, the 1900+ attendees gave him the kind of reception reserved for living masters.

A fine recording of that 2023 performance has just been issued as 3 (Gearbox), and it brought me back in my mind’s ear to the same hall about eight months before, when I was there in person to hear Ibrahim play a solo recital. Londoners revere Ibrahim, and they listen to him in pin-drop silence. They know that he is an icon of Black liberation, a carrier of ancient African tradition, and a well of indelible melodies. They treasure every minute they can spend in his presence.

No recording can really do justice to one of his concerts, for at least two reasons. First, there is a special atmosphere that accompanies him to the stage. Those who come to hear him know that they are in the presence of someone important. Even now, when he has grown frail and must be accompanied as he walks to the piano, he has a majesty that inspires awe.

Second, his performances have an anything-can-happen quality, even when every detail has been planned. A recording always presents a replication of an event, and it freezes the electricity of the living time. As Eric Dolphy said, “When the music’s over, it’s gone, into the air. You can never capture it again.”

So you must see Abdullah Ibrahim live if you can. He is due to appear this year in New York on April 26 and 27 in a pair of Harlem Stage Gatehouse concerts celebrating Duke Ellington curated by Jason Moran, and to return to the US on November 10 for a solo concert at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia. We can hope that his health holds out to allow him more performances here.

For now, 3 gives you the chance to hear Ibrahim as he is today, reflecting on his legacy, reinvigorating that legacy, and giving generous stage time to two outstanding players who know his music intimately from years of working with him.

The new recording holds a number of surprises, not the least of which is the length of the performances. Of the 16 individual tracks spanning 99+ minutes, only eight last longer than six minutes — and one of these just edges the border at 6:01. Two of these are long piano solos, followed immediately by compact trio performances of Ibrahim originals. Although the time of each of these medleys is around 20 minutes, they feel shorter because of the way in which Ibrahim spins many threads into his solos (more about that in a moment).

Another surprise is the first set, six short expositions of Ibrahim themes performed in the same hall, but without the audience. Each of these is a straightforward interpretation with little or no improvisation. Ibrahim is present more as the leader than as soloist, although there are two brief piano solos.

Cleave Guyton Jr., with his arsenal (his right hand holds his piccolo). Photo: Facebook

And yet another surprise: the instrumentation. Cleave Guyton Jr. is mostly featured on flute (it sounds like alto flute to me, but that may be simply a reflection of how full Guyton’s sound is), and Noah Jackson mostly plays bass — covering both ends of the sound spectrum. In addition, the trio rarely plays as a trio; there is a feature for Jackson solo, and there are duets for Guyton and Jackson, in two cases without any piano, and in five others with only minimal commentary from Ibrahim.

Guyton has two extensive performances on piccolo, an instrument that Ibrahim likes and has used effectively in his working band, called Ekaya. Guyton manages to make this little axe sound richer than I have ever heard it on record, and his workout on “Tuang Guru,” an almost pianoless duet with very fast walking bass by Jackson, is remarkable. On the other hand, I quibble with the choice of piccolo for Thelonious Monk’s “Skippy,” a tune that I like to hear with a saxophone lead; the high notes of the piccolo make the tune sound frivolous rather than forceful. When Guyton played it (again on piccolo) on Ibrahim’s The Balance (Gearbox, 2019), he had the support of the other players in Ekaya; here he must carry the weight all by himself.

Pianist Abdullah Ibrahim today. Photo: Dr. Marina Umari

Jackson’s bass playing is crucial; his pitch is secure, and his time never falters. He also plays cello (on “Barakat,” “The Wedding,” and both takes of “Mindif”). His sound on both instruments is gorgeous, but I would have liked to have heard a better solo bass feature for him than John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps.” He shows off an admirable ability to work through the changes on the Coltrane tune, but there is little opportunity to hear how beautiful he can sound; that is offset somewhat by a duet version of Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood,” where he glows.

I would warn the listener not to put too much weight on the performance of “The Wedding” on 3. Ibrahim has recorded this composition many times, usually with some instrumental variation on the originals, which date from the ’70s. Here he has Guyton playing clarinet and Jackson playing cello, and the combination is simply not as effective as other recorded versions of the song (see “More” below).

This generosity of feature space is typical of the leader, who loves to show off the soloists in Ekaya. But let’s face it: we are here to hear Abdullah Ibrahim. When he plays — even when he is playing without any accompaniment from the other two — the set coalesces and becomes an Abdullah Ibrahim performance.

His two long solos, both called “Reprise,” are not rhapsodies on a single song line, but rather excerpts of what he has done for decades in his marathon solo performances — indeed, what I heard him do some months before in London when he played alone. He strings together his own familiar themes, flashes of what might be other composers’ tunes or chords, fantasies on chords he likes, improvised melodies, and perhaps some folk-themes as well. All flow together seamlessly in a warm bath of sound.

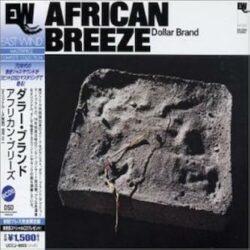

Ibrahim’s solos today are not like those of his early maturity (like the powerful African Piano / Live at Jazzhus Montmartre, 1969 [Enja, 1973] or African Breeze [East Wind, 1974], recorded in concert in Japan). Those performances could boil as well as simmer, and both ended with rollicking versions of his 6/8 blues, “Tintinyana.” The octogenarian Ibrahim no longer tries to impress; he doesn’t need to do anything more than be himself at his most lyrical.

Ibrahim’s solos today are not like those of his early maturity (like the powerful African Piano / Live at Jazzhus Montmartre, 1969 [Enja, 1973] or African Breeze [East Wind, 1974], recorded in concert in Japan). Those performances could boil as well as simmer, and both ended with rollicking versions of his 6/8 blues, “Tintinyana.” The octogenarian Ibrahim no longer tries to impress; he doesn’t need to do anything more than be himself at his most lyrical.

This recording ends, as the concert I heard did, with a poignant second encore. After one round of enthusiastic applause, an encore by the trio, and a second round of shouts from the audience, Ibrahim returned to the stage to sing, unaccompanied and unamplified. His simple song, “Trance-Mission,” paints in a few brief strokes a portrait of an enslaved person in distant exile: “Welcome home / There’s no one to welcome me home / I see the harbor lights / Africa far far away / I hope I’ll see my home again someday.” (Yes, a lot of Londoners made money in the slave trade, too.)

Artist as conscience, as mentor, as inspiration, as icon. We still have Abdullah Ibrahim among us, and we are lucky.

More:

3 is available in digital form on Bandcamp, and is also hearable on Spotify.

If you are not yet familiar with Abdullah Ibrahim’s work, I suggest you begin by buying one of the first Ekaya releases: African Marketplace (Elektra, 1980) or Water from an Ancient Well (Enja, 1986). Here you will find some of his most beautiful melodies – “Moniebah,” “Mamma,” “Mannenberg Revisited” (aka “Cape Town Fringe”), and, most importantly, “The Wedding,” which is given definitive performances by alto saxophonist Carlos Ward on both discs — although I prefer the one on African Marketplace, because Ibrahim plays a concert grand rather than electric piano, as he does on Water from an Ancient Well. Each of these recordings presents an outstanding edition of Ekaya — Marketplace has trombonist Craig Harris and bassist Cecil McBee among its crew, and Water has tenor player Ricky Ford and Thelonious Monk’s drummer Ben Riley. Neither of these releases is hearable on Spotify. You will not go wrong owning either in CD form.

The Balance (Gearbox, 2019) is one of the more recent Ekaya releases. The band in that edition includes both Guyton and Jackson, the featured players on 3. The Balance has ensemble versions of several compositions heard on 3: “Dreamtime,” “Nisa,” “Tuang Guru,” and “Skippy.” This is hearable on Spotify.

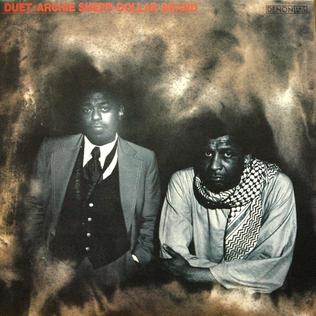

One of the most interesting releases in Ibrahim’s discography is Duet (Denon [Japan], 1978), co-led by saxophonist Archie Shepp, with Ibrahim billed as “Dollar Brand,” the name he used before converting to Islam. It was considered an unusual pairing at the time, but now seems inspired. Shepp’s return to traditional forms in the ’70s (along with a newfound reverence for Ben Webster-ish balladry) coincided with Ibrahim’s increasing interest in melody. This session finds them in perfect synchrony. Ibrahim’s “Moniebah” and the Mal Waldron tune “Left Alone” (made famous by Billie Holiday) are standouts. This is also hearable on Spotify.

One of the most interesting releases in Ibrahim’s discography is Duet (Denon [Japan], 1978), co-led by saxophonist Archie Shepp, with Ibrahim billed as “Dollar Brand,” the name he used before converting to Islam. It was considered an unusual pairing at the time, but now seems inspired. Shepp’s return to traditional forms in the ’70s (along with a newfound reverence for Ben Webster-ish balladry) coincided with Ibrahim’s increasing interest in melody. This session finds them in perfect synchrony. Ibrahim’s “Moniebah” and the Mal Waldron tune “Left Alone” (made famous by Billie Holiday) are standouts. This is also hearable on Spotify.

I hesitate to recommend any of Ibrahim’s solo piano recordings, although each is fascinating. 3 will give a first-time listener a couple of excellent solo piano samples in the two “Reprise” performances.

To really understand his conception of the solo performance, you should see Ibrahim live first, and then listen to samples of the solo work on line. Then you can choose which of the solo recordings you will want to hear again and again. For me, the two I refer to above — African Piano / Live at Jazzhus Montmartre, 1969 [Enja, 1973] and African Breeze [East Wind, 1974] — are pinnacles.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

🤍 Thanks, Steve.