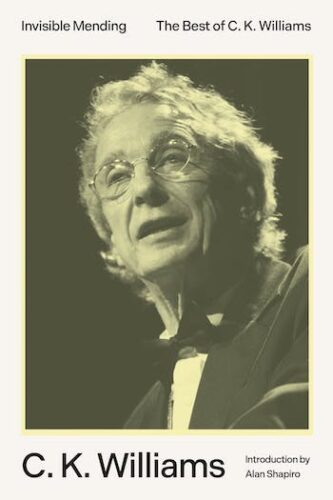

Poetry Review: According to Whom? — “Invisible Mending: The Best of C.K. Williams”

By Ann Leamon

I’m not against the concept of a Whitman’s Sampler of C.K. Williams poems — but this problematic selection proves that it should not be a family affair.

Invisible Mending: The Best of C.K. Williams. Introduction by Alan Shapiro. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 272 pages, (paperback) $25.

Few would dare to argue that C.K. Williams was not a great poet. Widespread critical acclaim and a fistful of prestigious awards testify to that fact. In fact, it’s probably quicker to note those of his 23 collections of poetry (including various compilations of his work) that didn’t win awards than those that did. Moreover, he wrote in a wide variety of genres, producing children’s books, scripts, songs, prose, essays, plays, and translations.

Few would dare to argue that C.K. Williams was not a great poet. Widespread critical acclaim and a fistful of prestigious awards testify to that fact. In fact, it’s probably quicker to note those of his 23 collections of poetry (including various compilations of his work) that didn’t win awards than those that did. Moreover, he wrote in a wide variety of genres, producing children’s books, scripts, songs, prose, essays, plays, and translations.

The development of his poetry is fascinating in its evolution from short-lined poems about then-current themes (the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement) to long-lined, introspective works that exuded a poetic sensibility. His topics ranged from the horrific — Nazi atrocities, the human capability for inflicting pain and how we live with that knowledge — to the quotidian, like the people in the park near his home, and even the humorous, such as intestinal gas. He wrote prolifically, taking to heart T.S. Eliot’s purported comment that a poet should write poetry every day.

Such fertility challenges a reader who wants to “get a taste” of C.K. Williams. A volume of his collected works would approach the size of the unabridged Oxford English Dictionary. Even his Collected Poems, published in 2006, runs to 704 pages, and that omits his last seven books.

There seems, then, to be a real need for a “Best Of” collection, an assemblage that would offer the quintessence of C.K. Williams. It might be best considered a “Whitman’s Sampler” of the poet’s work, a one-pound variety assortment that offers something for a variety of tastes without leading to surfeit.

When I send a Whitman’s Sampler to friends and family, I’m aware that it will inevitably omit some particular favorites. In its manageable 242 pages, Invisible Mending manages to gather an adequate number of gems from an impressive career. Still, those who know the poet and the impressive range of his work will find themselves searching in vain for what they consider to be his most memorable pieces.

Part of that disappointment might be attributed to the structure of Invisible Mending, which has its weaknesses. First off, the volume is presented as “the best,” not simply “an assortment.” That raises an important question: who made the choices and on what grounds? The frontispiece tells the reader that the selectors were made up of Williams’s “family and friends.” That statement puts me on alert. Friends and family may pick poems for many reasons besides aesthetic merit: perhaps a wish to shape the poet’s legacy, making him appear wiser, kinder, and more serious than he was in real life. And were there personal debates among family members about what poems should be included?

In addition, any “best” collection that the poet does not produce will lack the dramatic arc of a single collection. For example, look at how Invisible Mending deals with Repair, Williams’s first Pulitzer prize–winning volume. Repair starts with “Ice,” which describes in glorious detail the fracture and melting of a block of ice, and ends with the poem “Invisible Mending,” an account of the seamstresses who once performed the titular task. The volume begins with fracture and dissolution and ends with an act of repair, a nod to the book’s title.

Invisible Mending includes 10 of Repair’s 38 poems. The volume’s selection begins with “Ice” and concludes with “Invisible Mending.” But in between these choices this self-proclaimed “best” collection leaves out poems that I would want included: “Biopsy,” its heartfelt terror capped by relief, and “Gas,” a lighthearted meditation on intestinal gas that concludes with the stallion who couldn’t be ridden and the stanza “[…]I didn’t know if I/ wanted to break him or be him.”

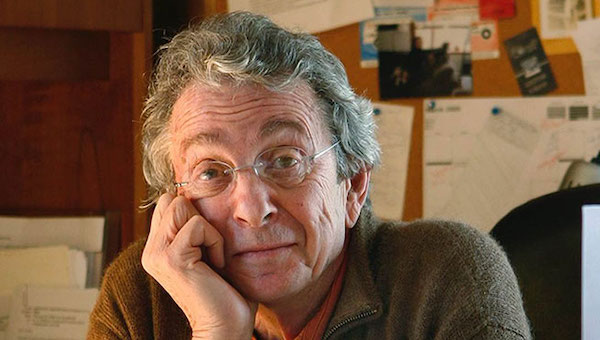

C.K. Williams. Photo: Tom Grimes

What’s more, Invisible Mending includes some poems I would not list among Williams’s best. “Owen: Seven Days” from Repair, a painstaking description of Williams’s first grandson at a week old, lacks the inventiveness of many of the other poems in that volume.

And then there is the matter of organization. Although the first and last poems of Repair are positioned that way in Invisible Mending, the order of the eight that come between has been altered, which slightly revises the thematic/dramatic resonance of the original.

What would have been a more successful structure for a “Best of” C.K. Williams collection? The selectors should have been made to briefly describe who they are and why they made their choices. Was “Owen” selected by Owen himself? “Swifts” is a swooping, exalting description of those birds, but why not include the revelatory “Dirt,” which focuses on Williams’s grandmother washing out his mouth with soap? Here is that poem’s ending:

Dare I admit that after she did it

I never really loved her again.

She lived to a hundred, even then.

All along it was the sadness, the squalor,

But I never, until now, loved her again.

Did the selectors cringe because of that blunt assessment? Even though the speaker reconciles with the humiliation and his grandmother’s overreaction? The ending line tells us that — eventually — he forgave her.

There is a powerful argument to be made that the poems as ordered in their original collections have the final say on the poet’s intent. Removing the poems from their original thematic context diminishes their power. At the very least, an explanation should be provided, a rationale detailing why some poems were included and not others. If family and friends are not willing to provide an explanation, then the task of choosing should go to academics or Williams experts who would select their favorite works and describe the reasons behind their choices. That would generate a welcome critical dialogue about criteria and merit. I’m not against there being a Whitman’s Sampler of C.K. Williams poems — but this problematic selection proves that it should not be a family affair.

Ann Leamon’s writing spans the genres and has appeared or is forthcoming in Harvard Review, Tupelo Quarterly, MicroLit Almanac, North Dakota Quarterly, and River Teeth, among others. She holds a BA (Honors) in German from Dalhousie University/University of King’s College, an MA in Economics from the University of Montana, and an MFA in Poetry from the Bennington Writing Seminars. She has attended residencies at the Prospect Street Writing House, Blackfly Writing Program at the Haystack School, Stonecoast Writers Program, and Dorland Mountain Artists Colony. She lives on the coast of Maine with her husband and a Corgi-Lab mix.

Disclaimer: I am family.

That revealed, I look forward to reading every one of Ann’s reviews because I learn something from each one. In this current one she taught me to look at a volume of poetry as a whole, with its own message. I also love language, well and accurately used, a skill/art Ann puts to use to make her reviews a delight for my ear.