Music Commentary: In Memoriam, Seiji Ozawa (1935-2024)

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Taking in the totality of Seiji Ozawa’s life and career, it seems clear that Boston got him in his prime and that he largely returned the favor, ingratiating himself with the community, at times truly elevating the BSO while conveying a lot of joy and energy in the process.

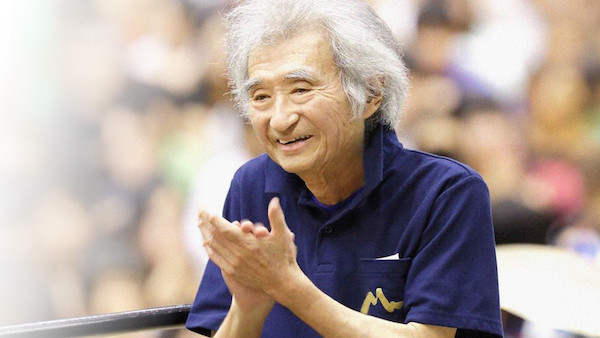

The late Seiji Ozawa. Photo: Michiharu Okubo

The death of Seiji Ozawa on February 6 marks the end of an era for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which he led for 29 years, between 1973 and 2002.

More significantly, it all but closes the book on the generation of conductors born in the late-1920s and ’30s who helped define classical orchestral music in the postwar era. Though in recent years his appearances were limited by illness, Ozawa was one of the last active members of the generation of conductors that included Herbert Blomstedt, André Previn, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Claudio Abbado, Lorin Maazel, and Carlos Kleiber. Of those leading lights, just Blomstedt remains.

Ozawa was, of course, the only non-European of that number, the child of Japanese parents living in occupied China (after his father began displaying sympathy toward the plight of the occupied Chinese, the family was deported back to the home islands). Almost out of necessity, his career followed a singular, and singularly unpredictable, path.

After breaking two fingers playing rugby, Ozawa gave up plans to become a pianist. Instead, he studied conducting with Hideo Saito. On winning a conducting competition in Besançon, France, in 1959, he was invited by then-BSO music director Charles Munch (who was on the jury) to study at Tanglewood. A year working with Herbert von Karajan in Berlin came next, followed by Ozawa’s appointment as an assistant conductor at the New York Philharmonic under Leonard Bernstein.

In 1965 — on Bernstein’s recommendation — he was offered the directorship of the Toronto Symphony. Three years on, Ozawa was appointed to lead the Chicago Symphony’s summer festival at Ravinia. In 1970, he succeeded Josef Krips at the San Francisco Symphony and, in 1973, came to Boston. The rest, as they say, is history.

Those long Boston years were central to Ozawa’s career. By critical consensus, he stayed too long; when he left in 2002, the orchestra was more than ready for new leadership and Ozawa for fresh challenges. That impression still casts an outsize shadow on his legacy.

Having come to Boston in 2004, I can’t speak from firsthand experience to the ups and downs of the conductor’s decades in New England. My two encounters with him as BSO music director were positive ones: a spirited Tchaikovsky-Dvorak afternoon at Tanglewood in 1993 (with Itzhak Perlman playing the former’s Violin Concerto) and a stirring celebration of his tenure at Symphony Hall in October 2001.

But, even if Ozawa the music director who overstayed his welcome is the right one (and many of the problematic elements of his tenure boiled over in the ’90s), it’s worth noting that, when he arrived, the charismatic 38-year-old who took the podium — wearing turtlenecks and beaded necklaces, often conducting from memory — offered audiences at Symphony Hall a breath of fresh air. He conveyed youthful vigor, appeared regularly on television (including, memorably, on Sesame Street), and made a string of recordings that, half a century on, still hold up.

True, Ozawa’s repertoire preferences with the BSO – which remains legendary for its command of French music — leaned more Germanic than Gallic (with Bernstein and Karajan as his mentors, how could it have been otherwise?). But, to judge from his gigantic discography, Ozawa was a master of Berlioz, Ravel, and Poulenc. Messiaen and Dutilleux, too: one of the highlights of Tanglewood’s 75th birthday celebrations in 2012 was the release of a stupendous Turangalîla-Symphonie he led there in 1975.

In certain kinds of music Ozawa was truly second-to-none. Few conductors have so consistently exhibited his total mastery over large-scale works: just listen to his recordings with the BSO of Carmina Burana, Elektra, Gurre-Lieder, and — especially — Ottorino Respighi’s Roman Trilogy to see what I mean. Though it’s been underrated for 30 years, Ozawa’s Mahler cycle with the same forces has aged well, too.

His rapport with particular soloists is evident on various albums, especially those with Krystian Zimerman (terrific Liszt and Rachmaninoff discs), Perlman (recordings of concerti by Berg, Stravinsky, Bernstein, Barber, and Earl Kim among them), and Yo-Yo Ma (particularly in concertante works by Richard Strauss and Dvorak).

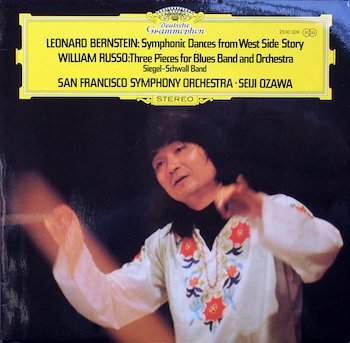

And, though Ozawa wasn’t a committed champion of American composers like Bernstein was, he made valuable documentations of music by Charles Griffes, Roger Sessions, and John Harbison. Indeed, no discussion of his recorded legacy is complete without mentioning one of his standout albums, this with the San Francisco Symphony, of two pieces by William Russo: the “blues concerto” Street Music and Three Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony Orchestra.

And, though Ozawa wasn’t a committed champion of American composers like Bernstein was, he made valuable documentations of music by Charles Griffes, Roger Sessions, and John Harbison. Indeed, no discussion of his recorded legacy is complete without mentioning one of his standout albums, this with the San Francisco Symphony, of two pieces by William Russo: the “blues concerto” Street Music and Three Pieces for Blues Band and Symphony Orchestra.

Yet throughout his career, Ozawa never lost sense of his Japanese roots. He was, perhaps, the finest advocate for his contemporary (and compatriot) Toru Takemitsu. In 1978, Ozawa led the BSO on a tour to his home country and, the next year, its first-ever tour to China. Fully a third of his 21 tours with the orchestra visited Asia, where the ensemble, thanks in part to its music director’s celebrity, played a major role in expanding the visibility of Western classical music on the continent.

How one balances these strengths with the less-positive aspects of Ozawa’s three decades in Boston remains an open question. The issues to be considered include regular press criticisms, the conductor’s overcommitments as a conductor and festival leader, periodic reports of an orchestra in rebellion, and a series of unpopular personnel decisions (most notoriously, removing Richard Ortner as administrator of the Tanglewood Music Center in 1997). At the very least, Ozawa had his shortcomings as a conductor and institutional leader.

In that, though, Ozawa was hardly exceptional. And taking in the totality of his life and career, it seems pretty clear that Boston got him in his prime and that he largely returned the favor, ingratiating himself with the community (where he became something of a fixture at Red Sox games), at times truly elevating the BSO while conveying a lot of joy and energy in the process. What’s more, to judge from the hundreds of reminiscences appearing online, Ozawa was also a wonderful ambassador for classical music, as friendly, approachable, and down-to-earth a musical star as they come.

Benjamin Zander, another approachable, charismatic, octogenarian local musical icon, often speaks of looking for the “shining eyes” during and after his performances and master classes, by which he means those who are engaged with what’s happening on the deepest level and can’t help but reflect that experience physically. With Ozawa, it seems that there was no shortage of shining eyes over an awfully long, rich, and varied career. By about any measure, that’s as beautiful a legacy to leave as it is, after nearly nine decades, an impressive one.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.