Book Review: Filmmakers and Their Opinions — as Told to Critic Gerald Peary

By David D’Arcy

New cinematic mavericks have come along. All the more reason that the views of earlier rebels be collected and preserved, given the short historical memories of young filmmakers and their audiences.

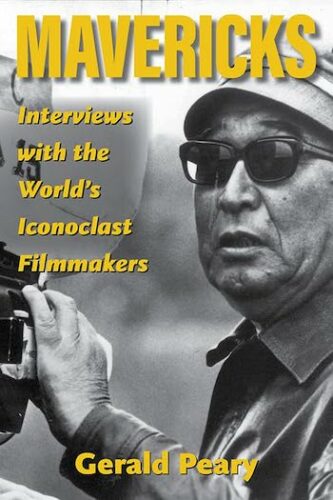

Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers by Gerald Peary. University Press of Kentucky, 204 pages. 26 b&w illustrations, $40.

The title of veteran local film critic (and Art Fuse contributor) Gerald Peary’s Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers is broad enough to include directors from Akira Kurosawa to Bernardo Bertolucci and Liv Ullmann, from Mel Brooks to John Waters and Agnieszka Holland. He speaks with Gillo Pontecorvo, director of the 1966 classic The Battle of Algiers and talks to Roberta Findlay, the maker of Snuff (1976) and other pornographic films, sometimes dressed up these days in the genre of “exploitation.”

The title of veteran local film critic (and Art Fuse contributor) Gerald Peary’s Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers is broad enough to include directors from Akira Kurosawa to Bernardo Bertolucci and Liv Ullmann, from Mel Brooks to John Waters and Agnieszka Holland. He speaks with Gillo Pontecorvo, director of the 1966 classic The Battle of Algiers and talks to Roberta Findlay, the maker of Snuff (1976) and other pornographic films, sometimes dressed up these days in the genre of “exploitation.”

Why mavericks? Is it a word that critic Peter Biskind hadn’t put in a title yet?

Most of the collected pieces by Peary are newspaper articles, plus some long conversations in question and answer form. He wastes no time with the etymology of maverick in his brief introduction. His approach seems to be to get directors to talk about their work. The result is a mixed bag, as varied as his interlocutors. The interviews were done between the late ’70s and the mid 2000s, decades when the business of film evolved away from studio control — and all sorts of people made films for the first time.

That evolution has now gone far beyond the people in this book, some of whom can be eloquent, even defiant. Martin Ritt (Hud, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, The Front, Norma Rae) was a labor militant in a town (Hollywood) run by corporate executives. Ritt wore the same “Middle American” leisure suits day after day as an act of rebellion. “If a thief opened my closet, he’d scream, ‘For what?’” And he still made studio films. Being friends with Paul Newman didn’t hurt.

The French filmmaker Benôit Jacquot (someone’s maverick) speaks like a male holdover from a bygone era, repeating wistful musings on filming young girls. But bear in mind that Jacquot began in filmmaking as an assistant director to Marguerite Duras when women directors were rare in France. One of those young actresses, Judith Godrèche, has now accused Jacquot of “predation” and “violent rape of a minor under 15 years old committed by a person in authority.” It’s reassuring to learn that such an offense is a crime in France. Jacquot denies the charges.

For filmmakers trying to be mavericks, failure was (and is) more of a certainty than success. Peary visits uber-maverick Norman Mailer, then 63 in 1987, with a few films and a brawler’s reputation under his belt, shooting Tough Guys Don’t Dance in Provincetown with the late Ryan O’Neal — a fellow boxer, we’re told. “I have a literary sense that I can apply to film. Because of my writing background, I have a sense of character that is deeper than a lot of directors,” Mailer tells Peary. “What you want is for it to be seen as an art film thirty years after it was made, not two weeks after it comes out.”

Released in 1987, Tough Guys Don’t Dance failed to earn back one-tenth of its $5 million budget.

Sometimes, as with Marcel Ophuls, discussing one’s work meant responding to the judgments of another presumed maverick, Jean-Luc Godard, who dismissed The Sorrow and the Pity (1969), the influential four-hour documentary about the French city of Clermont-Ferrand under the Nazi Occupation, as a “Hollywood film.”

“I don’t know what Godard thinks of the film,” Ophuls tells Peary. “I don’t know if he dislikes it as much as I dislike his films. But if someone called The Sorrow and the Pity a Hollywood film, would I be insulted? No, I think there is a great deal of truth in that statement. It’s a work by someone who’s trying to tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, by means of sex, music, cutting, and manipulation. I’ve seen a great many American movies in my life. I’m the son of a moviemaker. Perhaps I have very classical taste. Different from most documentarians, I believe in trying to put things across through entertainment…. Most of the directors I like are comedy directors like Lubitsch.”

Who knew?

Arts Fuse critic and filmmaker Gerald Peary. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Mel Brooks is anointed here as a maverick, even though his features were all studio films. Pushing back the walls of ignorance, one farce at a time?

Brooks, not one to be stigmatized as too serious, reveals to Peary that he tests his gags systematically with ordinary people before a film is made, to make sure the jokes work. “The Producers (1967) lives because it is well-constructed, and not because of ’Springtime for Hitler,’” he declares.

Pushed by Peary, Brooks bristled at the idea that there were no politics in his comedies. “The Producers was about love and greed, and it’s also about neo-Nazis. I thought it was the best way to handle Hitler. To treat him ludicrously is to do more damage than to get on a soapbox and rail.” In his burlesque Western Blazing Saddles (1974), “I treated racial intolerance, bigotry, homosexual love,” Brooks insists. A few paragraphs later, Brooks admits, “I leave my heart and soul in my apartment. My job instead is to bring jellies and jams to your local theater.”

Sex in porno films for Roberta Findley was like laughs in Mel Brooks’s comedies. “I try to make a reason for everybody screwing,” she told Peary in a fascinating interview in 1978, around the time when “XXX” porn (Deep Throat, her much publicized Snuff, Behind the Green Door, etc.) was a much-hyped forbidden fruit. Porn got its mainstream 15 minutes then, branded as chic slumming for audiences seeking a thrill.

“Pornographic films are like opera,” Findley says. “You have the opera story but then everything stops when the soprano has to sing an aria. It’s the same thing in sex films. The story goes on, then it stops, the script has stopped, they have to screw. Sorry to compare pornography to opera. I really think more of opera than that.”

Just getting into theaters proved to be a struggle in the case of John Waters’s film Pecker (1998), a prescient comedy about the rise of a Baltimore boy photographer thrust into New York’s trendy art world.

Waters tells Peary that he fought to keep a title that the Motion Picture Association of America found objectionable: “I’m not that innocent not to know there’s a double entendre. But it’s a joke, the boy’s nickname, because he picked at his food as a child. Originally the MPAA turned down the title, and we went to court about it. My lawyers had a list of titles to show them like Shaft, Free Willy, In & Out, and I gave a little speech saying, ‘Pecker might be vulgar, but it’s not an obscene word,’ and ‘This is a movie about someone who wants his good name back. And in this case the good name is Pecker.’”

“Very Frank Capra,” Peary notes.

Director John Waters filming 1998’s Pecker. Photo: Wiki Common

Soon marquees across the country displayed “John Waters’ PECKER.” Somehow MPAA monitors were more lenient — if they even noticed — about the film’s scenes of a local practice called teabagging at Baltimore’s Fudge Bar.

Continuing in the vein of American moralism, Peary talks to German director Volker Schlöndorff and Margaret Atwood about the 1990 film adaptation of Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale. The novelist, who did not write the screenplay, explains that “one of the persons it’s dedicated to is Perry Miller, through whom I studied at Harvard the American Puritans in great detail. The roots of totalitarianism in America are found, I discovered, in the theocracy of the seventeenth century. The Scarlet Letter (1850) is not that far behind The Handmaid’s Tale, my take on American Puritanism.”

“It’s naïve to think that all women are moral and good,” she tells Peary. “Are women more peaceful than men?” she goes on to ask.”They have a more vested interest in peace because of raising children, but we have no test case for women totally in control. If there was a special gene that every woman has, how do you explain Margaret Thatcher?”

Palestinian filmmaker Hany Abu-Assad. Photo: MAD Distribution

Understandably, for a book published in 2023 whose interviews are rooted in the politics at the time the conversations occurred, its politics have been overtaken by the views of new mavericks, and by their movies. All the more reason that the views of earlier generations be collected and preserved, given the short historical memories of young filmmakers and their audiences.

Case in point: the last conversation in Mavericks. In 2005, Peary published an interview with the Palestinian filmmaker Hany Abu-Assad, whose film Paradise Now treaded on delicate ground between humor and horror in a story of two suicide bombers dressed in dark suits like the Blues Brothers, characters in the hit Hollywood film.

Those were different days. Abu-Assad filmed in Israel, with plenty of official help, including the loan of a bus. The film played at the Haifa International Film Festival in an atmosphere that seemed oddly harmonious. Looking back, to cite a French slang term for behavior that seems artificial, c’était du cinéma.

What eventually happens in Paradise Now didn’t matter, said Abu-Assad, departing from his film’s tone of lighthearted bemusement. “When your life on earth is hell, it’s unacceptable, then you start to believe in heaven and paradise. There’s a need to have this belief when there’s no justice.”

It was striking to read that sentence after the October 7 attacks. Time for another interview.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: cinema, director interviews, Film, film directors, Gerald Peary