Visual Arts Review: “Deeply Rooted: Faith in Reproductive Justice” — Religion and Rights

By Jacqueline Houton

The overall impression of this valuable exhibit is to remind us that religious conviction is by no means synonymous with conservatism.

Deeply Rooted: Faith in Reproductive Justice at Brandeis University’s Kniznick Gallery, Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, Waltham, through February 1.

Giovanna Pizzoferrato Ribeiro, Portrait of Saint Lucy Holding Her Own Eyeballs, 2021. Glazed ceramic, 12.25 in. diameter. Photo: Amy Shelton

The first piece I laid eyes on in Deeply Rooted: Faith in Reproductive Justice, was Giovanna Pizzoferrato Ribeiro’s Portrait of Saint Lucy Holding Her Own Eyeballs (2021). This work instantly brought me back to a gift from my Catholic girlhood called Lives and Legends of the Saints — a book full of beautiful paintings and gruesome tortures. I remember being especially disturbed by the story of Saint Lucy because some of her suffering was self-inflicted: in that version of the tale, she tears out her own eyes and sends them to a suitor who claimed to have been rendered sleepless by their beauty. (God then miraculously restores her sight, though he declines to swoop in to save her from martyrdom.)

Ribeiro, a painter who pivoted to ceramics during the pandemic, saw her own early images of Saint Lucy in her mother’s homeland, Brazil, where many people carry pictures of saints in purses and wallets or on necklaces close to their heart. Here, on a ceramic plate, the artist offers a close-up view of Lucy holding her own eyes on a platter, pupils peering upward and slightly to one side. Is she gazing heavenward, I wonder, or rolling her eyes? In the wall text, Ribeiro notes, “To me, Lucy is the patron saint of ‘No, I will not be your baby maker. I’d rather pluck out my own eyes, Sir.’ While Catholics revere her for maintaining her virginity, I admire Lucy for defending her reproductive rights.”

Charlie Dov Schön, Post-Roe Protection Amulet, 2023. Felt, norgestimate (birth control – brand Sprintec), beads, ribbon, lace, thread, 5 x 2 in. Photo: courtesy of Brandeis University

Ribeiro’s piece underscores that the stories we tell are always subject to multiple interpretations. Indeed, the exhibit as a whole emphasizes that views on reproductive ethics vary widely among people shaped by spiritual traditions. Artist and curator Caron Tabb initially conceived of Deeply Rooted after the leak of the Dobbs decision; she envisioned an exhibition that would explore Jewish views of abortion and reproductive justice and rebut Justice Alito’s assertion that “the right to abortion is not deeply rooted in the nation’s history and tradition.” But she broadened the scope over time, gathering works by 21 artists representing a range of beliefs and backgrounds. The exhibition also prominently showcases the reactions of visitors, who are invited to scrawl their thoughts in chalk on a blackboard and on note cards. The results remind us that religious conviction should not be seen as synonymous with conservatism. Particular sects may be fixated on punishment and control, but they need not have the final word on faiths whose essential visions are rooted in love and mercy.

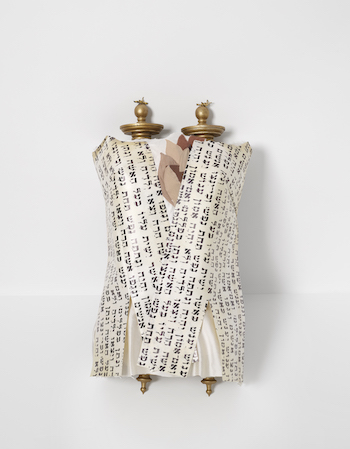

For a show with serious stakes, a sense of purposeful mischief pervades many of the works, which welcome witty inversions and subversions and juxtapositions. Several play with religious iconography of the past. Charlie Dov Schön’s Post-Roe Protection Amulets 1–5 (2023) features five charms inspired by 19th- and 20th-century amulets from across the Jewish diaspora. These modern-day talismans combine familiar craft supplies — felt, lace, beads, thread — with birth control pills, some still in their blister packs. Two triangles, two diamonds, and one circle — which might be a God’s eye or an ovum — dangle from ribbons, evincing a homespun cheer, a hope that small things can be powerful.

Marla L. McLeod, My Mother’s Keeper, 2023. Oil, burned and carved wood, 48 x 72 in. Installation view. Photo: Elizabeth Ellenwood

On another wall, Marla L. McLeod’s arresting trio of oil paintings, My Mothers’ Keeper (2023), sets her subjects against gold backgrounds that wouldn’t seem out of place on a medieval altarpiece. But these are all women of color born in the mid-20th century, maternal figures from McLeod’s own youth. Text burned into their surrounding invokes historical events that have marked these women’s lives, noting that one subject, Carrie Ingram, born in 1941, was 13 when schools were desegregated and 24 when the Civil Rights Act affirmed African Americans’ voting rights, that she bore her first daughter the year federal law barred sex-based wage discrimination and her second child the year after Roe. But the text also draws on personal memories of Ingram, who took McLeod into her home when the artist was a teenager. “She was never home. She worked a lot but would take time off to handle any school issues and usually took our side,” McLeod writes in cramped capital letters that force us to slow down and look closely as Ingram looks back with a steady, appraising gaze, one eyebrow ever so slightly raised. Ingram died at age 65, but her voice comes through, delivering a commandment by way of big block letters that frame her portrait: “Pass your classes and don’t get pregnant.” McLeod portrays her foster parent as complicated, human, and humane, a product of her time and a person worthy of veneration.

Winnie van der Rijn, Enemies At The Gate/My Body is a Sovereign Nation (Uterine Armor #7), 2023. Photo: courtesy of Brandeis University

Abortion is one through line, but the artists also tackle a number of other subjects. In The Ministry of Reproduction (3) (2014), Andi Arnovitz’s watercolors depict a developing fetus cradled in a crimson lining that fades into washes of pink and lilac. The delicacy of the image contrasts with the officious stamp in the corner, the imprint of the imaginary office referenced in the work’s title. It represents the power of conservative rabbis whose rulings can regulate women’s bodies — for instance, by prohibiting sex until a week after the end of a woman’s period (which can make conception more difficult, a phenomenon known as halachic infertility).

Janice Rubin’s Mikvah Project explores the ritual baths that form another aspect of these purity laws. Her photos of bodies in rippling water and shimmering light discover the potential for beauty in a rite premised on the notion that menstruation renders the body impure. They are accompanied by texts that reveal how women take myriad meanings from the tradition. For one woman, the mikvah is a chore that makes her look forward to menopause. For a survivor of domestic violence, the baths are a space where she has regained a sense of ownership over her own body. And for a woman who struggled with infertility for nearly a decade, mikvah represented a renewal of possibility at the start of a new cycle. Rubin’s camera captures her as she holds her baby close, wearing an expression of hard-earned delight.

A few works lack obvious connections to faith, but they deliver visual surprises that resonate with the show’s themes. Zoë Buckman’s According to Grandma (2019) packs a real punch: a pair of boxing gloves have been reupholstered in vintage linens, some of which belonged to the artist’s grandmother. Covered in lace, peppy plaids, and floral prints, these symbols of aggression are suspended at the height of a gym bag, seeming to invite us to work out our own. Winnie van der Rijn’s Enemies at the Gate/My Body Is a Sovereign Nation (Uterine Armor #7) (2023) indeed looks as if it has been through a battle. Street-sweeper bristles cut harsh lines across the crotch of vintage French bloomers ornamented by a handmade uterus and rust stains reminiscent of dried blood. It struck me as a relic from the past its wearer can hardly believe is being forced back into commission.

Caron Tabb, My Sister’s Keeper 2, 2023. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Julia Featheringhill

Susan Chen’s fun Free Tampax (2023) presents a ceramic carton with real tampons inside for the taking. The work nods to the push to end the “tampon tax” that remains in effect in 21 states, as well as efforts to make menstrual products free in prisons, schools, and other public facilities. On the back of the box, Chen calls our attention to the brand’s slogan — “Out of sight, out of mind protection” — alluding to lingering taboos that undercut public discussions about basic biology. (Chen herself grew up in a somewhat conservative family in a community where schools provided no sex education or mention of menstruation until high school; when she got her first period, she thought she had cancer.)

The exhibition catalogue incorporates Jewish, Christian, and Muslim perspectives on abortion and other topics from religious scholars. Wall text featuring the voices of the artists adds helpful context; I would have loved a smidge more in a few instances. That was the case with the video-painting Colorist (2019) by the Safarani Sisters, the moniker of the Iranian-born twins Farzaneh and Bahareh Safarani. Working in oil on canvas, they capture a woman seated in a corner like a kid on a time-out, eyes downcast, hands folded, red fabric draped over her lap. Behind her on a chair of its own sits an abstract painting rendered in shades ranging from scarlet to maroon; the picture leans against a white wall that’s bare but for a few subtle spatters of faded red. Suddenly, a video projection activates the painting: a bucket’s worth of bright red paint — or blood — pours down the wall. There’s a clear suggestion of violence (remembered or anticipated violence, maybe), but I wasn’t entirely sure how the work connects to the exhibition’s themes.

On the other hand, in a show steeped in faith, there is always a good case to be made to remain open to mystery. Dell M. Hamilton’s Deeply Rooted After Dobbs (2023) feels like one. Its tower of tulle and finger cots is bisected by an anatomical pelvis, threaded with blue synthetic hair — a tribute to Yemaya, Yoruba goddess of the seas — and stuffed with shredded copies of the Dobbs decision, which fall upon a Bible opened to Luke 8:43. Hamilton’s work had me looking up that passage and, while I was at it, one from Matthew that had been rattling around my head as I wandered about the exhibit. The passage has been on my mind in recent months as I read about the Texas and Ohio’s cruelty to Brittany Watts and Kate Cox and wondered what kind of moral calculus that would decree that zygotes are people while cutting back on aid to kids in poverty. I’d forgotten that after Jesus, quoting Hosea, instructs “But go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy and not sacrifice’” in Matthew 9:13, he repeats the line in Matthew 12:7. Jesus rarely repeats himself. It’s as though he’s saying something vitally important and knows his disciples weren’t listening then — and aren’t listening now.

Jacqueline Houton currently copyedits kids’ and YA books by day and serves as a senior editor at Boston Art Review. She is a former editor of the Improper Bostonian and former managing editor of the Phoenix and STUFF magazine (RIP x3). Her writing has appeared in Big Red & Shiny, Bitch magazine, Boston magazine, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, Pangyrus, Publishers Weekly, and other publications.

Tagged: Deeply Rooted: Faith in Reproductive Justice, Hadassah-Brandeis Institute