Book Review: “The Soundies” — A Definitive Study of the Musical Film Shorts of the ’40s

By Steve Provizer

Author Mark Cantor has been the go-to guy for jazz film for decades; this authoritative book solidifies his position.

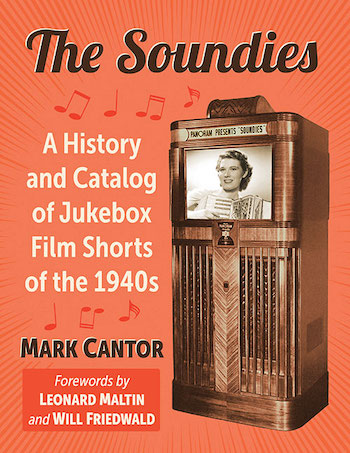

The Soundies: A History and Catalog of Jukebox Films of the 1940s by Mark Cantor. McFarland, 893 pages.

New technology has always been mobilized to deliver entertainment. When the dits and dahs of telemetry joined forces with Edison’s “Mary had a little lamb…” and Hertz’s waves, the resulting sound was quickly distributed via wax cylinders, shellac 78 RPM records, and — more ethereally speaking — radio.

Entrepreneurs have always known that Americans like their entertainment on demand (sound familiar?). So, financial movers and shakers quickly moved to set up nickelodeons and, in due time, jukeboxes in arcades, cafes, bars, and clubs across the US.

Most people know little about it now, but an innovative technology briefly supplied America entertainment starting around 1940. Almost 30 companies popped up to produce machines tailored to show short musical films anywhere people gathered for amusement and relaxation. The would-be media moguls behind this arrangement called their creations Cinematone, Penny Phono jukebox, Musical Shorts, Ltd., Phonovision. Even popular ventriloquist Edgar Bergen tried it, backing something called Techniprocess.

It was a tough and competitive business. Every company but one went bust, and the losers took their machines down with them. There was one survivor: Mills Novelty Co. of Chicago, which created Soundies. The 3-minute films were put out by the Soundies Distributing Corp of America (SDCA); the machines on which they were played were called Panorams. Mills already made slot machines, gambling devices, jukeboxes, player pianos, soda and cigarette vending machines. The business had the expertise and infrastructure to survive from 1941 to 1947.

Author Mark Cantor tracks this fascinating phenomenon in his authoritative tome, The Soundies. For decades, the author has been the go-to guy for jazz film; this fine and informative book solidifies his status. Not only has Cantor managed to track down the 1,869 Soundies that were released, but he has dug up plenty of background information about his finds: producer, director, release date, catalogue number, song title, lyricist, composer, arranger, location, instrumentalists, and a hell of a lot more. Cantor estimates that, in the machines’ heyday, there were about 3,500 Panorams and they could be found “in bars, taverns, poolrooms, community recreation rooms, hotel lobbies, restaurant foyers, defense industry break armed forces rec halls, etc. I have also found evidence that they were on some Manhattan ferry boats, and even a barbershop in Harlem.”

The book details why competitors failed and shows how SDCA managed to make the business work. Cantor also tracked down a number of people who were involved in making Soundies. I found these interviews fascinating, in part because they concretely delineate the itinerant, catch-as-catch-can life that most musicians and dancers led and how entertainers deftly moved between vaudeville, burlesque, radio, and theater to make their nut.

Unsurprisingly, the Soundie industry survived on a financial razor’s edge. There were plenty of obstacles. The wartime ban after 1941 on aluminum for nonmilitary use forced an end to production of the Panoram. During the musicians union strike of 1942-1944, SDCA had no choice but to draw on nonunion musicians, a cappella groups, and recorded prestrike material.

Over 50 production companies provided Soundies. Budgets dictated production values. Scenarios and sets were typically perfunctory, but clever set designers and an imaginative use of stock footage inspired some creative scenarios. Unfortunately, Cantor’s book doesn’t provide much detail about the backgrounds of the major producers and directors, such as William Forest Crouch, Sam Coslow and Josef Berne. One gets the impression that they’d had a background in making public relations material or small film projects, that they often wore several hats on a production, and that they knew how to squeeze an eagle till it screamed.

Below is “Emily Brown,” a 1943 Soundie performed by Bob Parrish and Chinky Grimes. Video provided by Cantor as seen on his website, Celluloid Improvisations.

Soundie producers trawled New York City nightclubs to find talent. Sometimes top stars were featured, but keeping costs low often meant that the leads, while professional, were not from the top show business echelon. If Soundies had been made in the ’50s or ’60s, they would have been staffed by competent lounge performers and backup bands from the Playboy Club circuit. Today’s Soundie talent would be scarfed from YouTubers whose numbers had yet to hit latest-rage levels.

Soloists — Meade Lux Lewis, Harry the Hipster Gibson, and Liberace among them — were popular, in large measure because it meant fewer musical mouths to feed and no arranger was necessary. There was only so much room in big Hollywood films for musical talent, either mainstream (think Dorseys, Crosby, Armstrong). Or exotic (think Madeleine Lebeau singing the “Marseillaise” in Casablanca or Yma Sumac singing “Virgin of the Sun God” in Secret of the Incas). Performers were happy for the cash and the exposure of the Soundies, especially Black talent, even those who’d already made some headway in Hollywood. For example, Dorothy Dandridge performed in a number of Soundies. A typical Soundie of this type would feature Hoagy Carmichael playing and singing “Lazy Bones,” with two lovelies draped on his piano, and Dandridge, in maid’s costume, dancing with another servant.

As noted, each Soundie was three minutes long, the length of a 78 rpm record. For technical reasons they were distributed eight at a time, on a single reel that was loaded into the Panoram. Each reel needed to have something to satisfy a range of musical tastes — focus groups and “target audiences” be damned. The company had three catalogues, so users were given the chance to assemble their own reels, but Cantor found very little evidence that they did: “The evidence suggests that even though users in Harlem, for example, certainly appreciated black talent, they also were happy to watch Jimmy Dorsey’s band, Liberace, crooner Skinny Ennis, or an act from the Florentine Gardens in Hollywood.” In today’s siloed aesthetic environment, this contentment with variety is somewhat astonishing.

One way producers dealt with marketing Soundies is that they distributed a wide a range of material that was rarely “pure.” Yes, there was some straight-ahead hot stuff from the likes of Erskine Hawkins (Soundie big bands were usually dance, not jazz, bands) and the Nat Cole Trio. And some Soundies were straight-ahead ethnic: Hungarian, Irish, Polka, etc. But arrangers and performers could slip a little jive/swing or vaudeville into almost any kind of music, be it Spanish, Hawaiian, Gypsy, calypso, or cowboy. The tune “I’m an Old Cowhand,” it turns out, can be put across in faux Italian, Irish, or Russian. A visit to Tinky tinky tonk tonk, a gay festival in Panama, is accompanied by a mandolin, while Minnie from Trinidad goes to Hollywood and changes her name to Minny Lamar. And there was always room for leggy chorus lines and tight sweaters, the kind of sex appeal that transcends language barriers.

Duke Ellington and his Orchestra in a ’40s Soundie. Photo: Mark Cantor

Was this kind of pop jazz-ethnic hybrid music fostered in any other country? Is Soundie content an early version of globalization? Watching Soundies today, the racial and gender prejudices of the era seem slightly less locked in place. Could it be that what we call “appropriation” can be harder to locate (and condemn) than we think? It’s hard to watch Soundies and not question the degree to which “genuine-ness” in cultural consumption is simply a fashionable trope, or whether the mere presence of a sombrero or a balalaika in an American film is enough to call “basta!”

There’s an odd lacuna in the history of Soundies. Cantor was exhaustive in his research, but there is one area that feels, at least to the historian in me, underexamined. While there are 125 photos and illustrations in this definitive study — and they are interesting — the only photos of the Panoram have the machines posed next to women in bathing suits or in-house executives. There are no photos of the 82-inch-high contraptions in situ, with watchers listening or dancing to Soundies. There is one Panoram prominent in a Soundie, but it was a setup for a Soundie itself. When you think of how many photos or films can be found with people engaging with jukeboxes, the omission seems odd.

The historical heart of The Soundies is its lengthy, detailed listing of each musical film. So the volume is akin to an expansive discography — with added essays, interviews, and graphics. The work comes in two volumes and the price is steep: this is a labor of love compiled for aficionados. But it is a pleasure to point budget-conscious readers to Cantor’s website, which contains an enormous amount of information and offers many Soundies and other short musical films to view. A number of Soundies can be found on YouTube. Watch them. Some may dazzle, some daze, some bore. But immersion will give you an opportunity to understand what entertainment meant in American culture — over 80 years ago.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.