Jazz Reviews and Appreciations: Sheila Jordan at 95 and Ran Blake at 88

By Steve Elman

It is something of a miracle that we can still hear Sheila Jordan and Ran Blake in live performance, and those experiences should be treasured by their audiences because those opportunities are so precious.

What you will read here is not impartial.

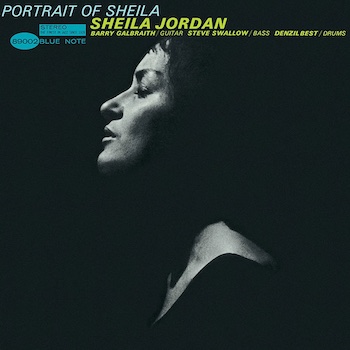

Jordan’s first release as a leader, 1961. Photo: Ziggy Willman

I have been lucky enough to know Sheila Jordan and Ran Blake well enough to call each of them by their first name. It is a special pleasure for me to see one of their faces light up with recognition when I can catch their attention for a few words before or after a concert. I esteem each of them. I revere each of them. I always consider it a privilege to hear one of them.

So I could not believe my good fortune to hear each of them in intimate concerts on successive days recently — Blake at MIT’s 140-seat Killian Hall on December 14, and Jordan at the 50-seat Baroness Room inside The Mad Monkfish in Central Square, Cambridge, on December 15.

Jordan is among the last survivors of the Bebop Generation. Charlie Parker, one of her musical heroes, said that she has “million-dollar ears,” and she sang alongside the originators of the musical style that the whole world plays now. Her work is still firmly rooted in those experiences, although she has sung in every conceivable jazz form since then. Her energy and inventiveness seem to be undiminished after 60 years of performing all over the world.

Blake, seven years younger, has absorbed in-person influences from every major jazz artist in their prime since before he began his quest as a pianist in the mid-1950s. Among his favorite memories is his stint as a dishwasher in a small club where Thelonious Monk’s group was playing — he could hear a master every night for free. Blake has become one of the most respected musicians in the world, rooting his work in the jazz tradition, but creating an original musical language that incorporates every kind of music he has heard along the way — blues, gospel, popular song, film music (especially the soundtracks of films noirs), Western classical music, the art music of non-Western cultures, ethnic music, and indigenous folk music.

Each of them endured years of obscurity.

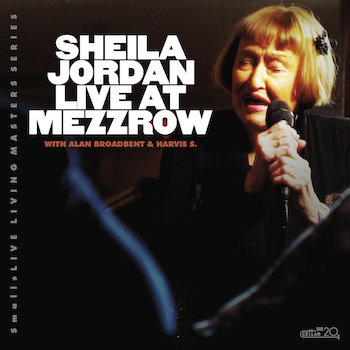

Jordan’s most recent recording (2022). Photo: Ross Mayfield

Jordan became one of the forgotten beboppers after she had to curtail her musical activities radically to earn enough money to raise her daughter as a single mother. When she was ready to return to performing full-time, she had to rebuild her career from the ground up. She had some of her first comeback successes here in the Boston area.

Blake never was conventional in his approach to music or to the piano. He was unwavering in a personal conception of his art, which initially baffled all but a few who heard it — not because it was Cecil Taylor-complex, but because it had been distilled to essential gestures, shards of melody framed by dramatic silences and distinctive manipulations of the sound of the piano. His career also received a major boost in Boston, when Gunther Schuller named him to be the first chair of the New England Conservatory’s (then-named) Third Stream Department.

No one in music sounds like either of them, although hundreds (perhaps thousands) of players and singers have been influenced by each of them. Neither of them will ever sell out a stadium or fill a grand concert space. And this is fortunate, because their art is best appreciated in a small setting where you can hear every note.

It is something of a miracle that we can still hear them in live performance, and those experiences should be treasured by their audiences because those opportunities are so precious.

Jordan’s club date at The Mad Monkfish was the latest in a series of almost-yearly visits for her to Cambridge. The club’s management deserves our profound gratitude for showing such loyalty to a great artist over a long period of time. Each time she has played the Monkfish, she has worked with pianist Yoko Miwa and her trio, and the group has developed a warm rapport with the singer. It was clear in this 2023 performance that she has special regard for the sensitivity of bassist Brad Barrett, who repaid that regard with sympathetic support and fine soloing. Miwa is a great accompanist, and a superb soloist when she is given the spotlight. Scott Goulding is a solid force as a percussionist, driving the group when it’s appropriate, and playing softly in the right spots. Now that I have also seen Miwa’s group in a headline show at Scullers, I was impressed with how each member held back on their usually extroverted style when working with Jordan — a testament to their own musicality and the reverence they have for her.

Sheila Jordan, in her official portrait as a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master; she was inducted in 2012. Photo: Michael G. Stewart

Her repertoire in the first set covered the bases she likes to cover — bebop classics (“I Got Rhythm” blended with Charlie Parker’s “Anthropology” and “All God’s Children Got Rhythm” blended with Miles Davis’s “Little Willie Leaps”), tunes by others that she has made her own (Oscar Brown Jr.’s “Hum Drum Blues”), beautiful standards (Matt Dennis’s “Everything Happens to Me”), and a few surprises. On this night, the surprises included a neglected Kenny Dorham tune called “Fair Weather” and Leon Russell’s “A Song for You.”

For more than a decade, in addition to her impeccable scat singing, Jordan has amplified her interpretations with improvised musical monologues about her life that are effortlessly worked into the frames of the songs she’s singing. These often include some surprises of their own, as on this night. While singing “How Deep Is the Ocean,” she sang about her own fear of swimming, which originated when “my brother tried to drown me.”

Perhaps best of all, she is inspired by an audience. She loves singing here, says so repeatedly on stage, and revels in the love that radiates back from her listeners in Beantown and environs.

Like all masters, she makes everything she does sound perfectly natural, absolutely logical, intimately personal. If her voice is not what it was 20 years ago, her swing is as gorgeous as a heartbeat, her pitch is still dead-on (though her vibrato now is a lot wider than it used to be), and her drama is better than ever. (Overheard as she rehearsed a tune before beginning the set: “You may think I’m coming in late, but I know exactly where the beat is.”)

Is she 95? I wish I were as young as she is.

Also in her audience at the Monkfish were pianist Ran Blake and singer Dominique Eade, who had performed at Killian Hall the previous night.

Blake played for only three minutes or so in the Killian recital. He is frail now, and he sits in a wheelchair at the piano. He prefers to play in reduced light (or, as at Killian, in complete darkness). But his touch is the same as it has been since he was first heard on a remarkable duet recording with singer Jeanne Lee in 1961 (The Newest Sound Around, RCA, 1962). His sound is so distinctive that a single note, or a brief flurry of them, is unmistakably stamped with Blakeness.

Ran Blake (l) and DekTor. Photo: courtesy of the artist

His solo performance, and the entire evening of music at Killian, was dedicated to the life and memory of his beloved cat DekTor. If that theme seems less than profound, the music was anything but. Blake’s own portrait was carefully crafted, lovingly shaped, and filled with thoughtful spaces.

The obvious reverence each of the other performers has for Blake as an inspiration and a mentor was channeled through reminiscences about DekTor’s behavior and personality.

But how could an evening of mostly other people playing, singing, speaking, be considered a Ran Blake concert? Because Blake chose these artists and curated the performance, and because he is now a master mentor, a figure in music education akin to an elder in an African tribe or a guru in India, a kind of bodhisattva: he has achieved enlightenment, and he now devotes his life to helping others achieve it.

The essences of Blake’s teaching are elements that any musician can learn without leaving their chosen genres. But they are elements that it can take a lifetime to perfect. He asks students (temporarily) to set aside written scores or musical notepaper; to learn to recognize notes, chords, keys by ear; to hear the silences between the notes; to sing heard melodies until they can exactly reproduce the pitches; to open their ears to a huge array of creative sounds from many sources; to appreciate deeply each of the performances they encounter; in short, to hear. Once a student has embedded all these tools deep inside, they are prepared to play the authentic music that rises from their own hearts.

As a result, the musics at Killian, though all in solo or duet forms, ranged across the whole spectrum of art.

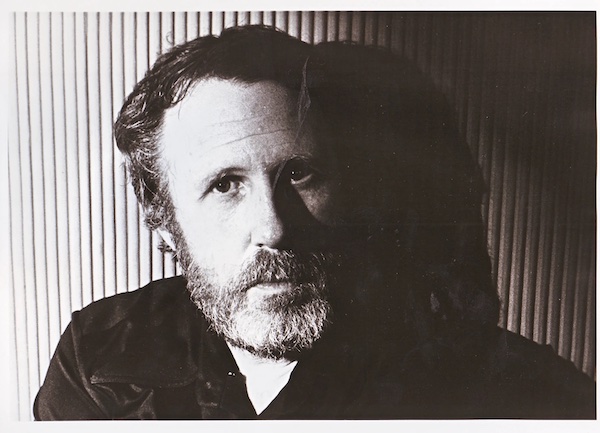

Ran Blake, c. 1980. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Some drew on the jazz tradition. The incomparable singer Dominique Eade gave an open reading to her own lyrics on Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints,” accompanying herself on the mbira. Saxophonist Daryl Lowery recognized DekTor’s Persian roots with a personal tribute that drew from Iranian tradition. Saxophonist Edmar Colón interpreted “Alma Adentro” by Puerto Rican songstress Sylvia Rexach. Itay Dayan offered a klezmer song on clarinet. A third saxophonist, Caleb Schmale, offered a free-form piece that “told a story,” as all good jazz improvisations should. Perhaps pianist Avi Randall showed the most direct influence of Blake when he played “When Autumn Sings,” a song introduced by Abbey Lincoln, whom Blake reveres as a mistress of space and shape.

There were other improvisations, from two non-Western traditions. Nima Janmohammadi played the kamancheh, a bowed instrument from Iran, and Yoona Kim played the ajaeng, a koto-like instrument from Korea, in which the pitches are controlled by pressure on the strings.

At the other end of the spectrum were pieces that were through-composed. Zander Grinnell offered Gershwin’s first piano prelude, Yukiko Takagi interpreted Chopin’s Nocturne No. 62, and singer-songwriter Emily Mitchell played and sang her own “Thankful.”

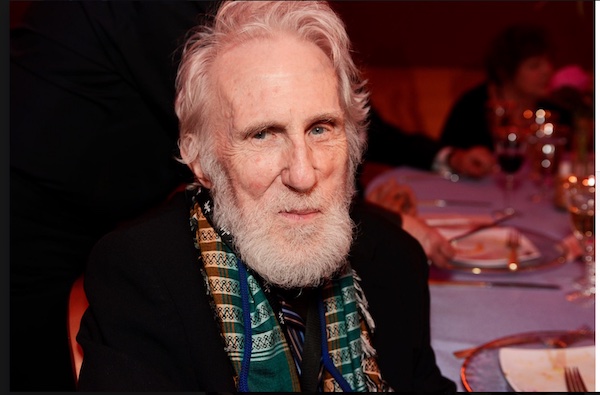

Ran Blake, Renaissance man. Photo: Andy Hurlbut

And beyond the spectrum: a poem by Ted Reichman and an electronic frame for a spoken text, composed and realized by Emiliano López.

As ever with these musical mosaics, whether offered under Blake’s direct supervision or in Jordan Hall concerts at the Conservatory directed by Blake’s successors as chairs of the Contemporary Musical Arts Department, Hankus Netsky and Eden MacAdam-Somer, the cumulative impact of such a performance is beyond expressing in a few words. Blended together for the listener are a sense of the breadth of creativity around the world, an awe of the diverse skill sets on display, and a knowledge that none of this would be happening here and now without Ran Blake.

On these two special evenings, I felt liberated from time. Ran Blake transcends it with his music and his life’s work. Sheila Jordan defies it every time she steps on stage. The memory of their music in these performances has helped me joyfully celebrate the transition into another year.

More:

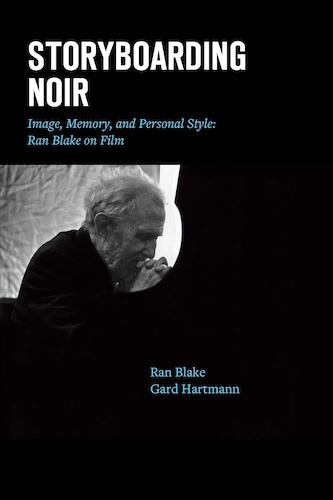

Ran Blake’s newest book, which “gives an inside view of [his] use of storyboarding, a filmmaking technique, which lies at the heart of his music-making.”

Blake’s enormous discography has many beautiful solo piano recitals, and some remarkable solos within larger projects. One of his most openhearted solos — and a great place for the new Blake listener to begin — is his interpretation of Horace Silver’s “Horace-Scope” from Horace is Blue: A Silver Noir (Hatology, 2000)

For an elegant example of Blake as an accompanist, a craft at which he excels, listen to Abbey Lincoln’s original recording of “When Autumn Sings” from her album Who Used to Dance (Verve, 1997), and then hear the duo version of the song by Blake and singer Sara Serpa, from their album Aurora (Clean Feed, 2012). The song itself is rich, and Lincoln sings her own lyric superbly. But the Blake – Serpa version makes time stand still.

Another brilliant recording of voice and piano is Town & Country (Sunnyside, 2017), for which Dominique Eade and Blake collaborated on an eclectic program. Their version of Bob Dylan’s “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” takes the tune to a place the composer never expected, but illuminatingly. Arts Fuse review of Town & Country.

Blake revels in encounters with musicians of all stripes. A particularly memorable meeting is captured on That Certain Feeling (George Gershwin Songbook) (Hatology, 2010), where he solos brilliantly on several tunes, duets on others with tenor saxophonist Ricky Ford (who began his career studying at NEC with Blake), duets on still others with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy (who held an academic position in the last years of his life at NEC), and brings the two saxophonists together for freeish trios, unforgettably on “Strike Up the Band,” where the three take the title literally. The Blake-Lacy essay from this disc on “The Man I Love” is also endlessly fascinating, since both musicians love the power of space. Their counterpoint in the last minute or so is perfect.

The truth: for an artist with such a huge discography, Blake’s creativity repays a listen to almost any track from any release at random.

The cover of Jordan’s excellent biography by Ellen Johnson (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016)

Sheila Jordan’s debut on record, Portrait of Sheila (Blue Note, 1961), with Steve Swallow (when he was still playing unamplified bass), legendary guitarist Barry Galbraith, and drummer Denzil Best, was breathtaking then and it is a revelation now. Tunes that she recorded there, especially “Baltimore Oriole,” have become signature songs for her.

Her landmark recording in George Russell’s recomposition of “You Are My Sunshine” with Russell’s small group (from The Outer View [Riverside, 1962]) showed how comfortable she was in challenging musical frameworks. Another “avant-garde” (albeit very good-natured) recording, Roswell Rudd’s Flexible Flyer (Arista / Freedom, 1974), contains “Suh Blah Blah Buh Sibi,” with scat singing that goes into previously uncharted territory and then swings with abandon.

Her collaborations with Steve Kuhn are sublime, though producer Manfred Eicher of ECM made the decision to record her on his label as he would a collaborating saxophonist — that is, less prominently than a singer is conventionally recorded. Kuhn’s “The Zoo,” from Playground (ECM, 1980; now available in Life’s Backward Glances, a retrospective Kuhn collection), is a great example of how effective she is at interpreting lyrics that are enigmatic (to say the least). For an instructive comparison, listen to her recording of the same tune as a leader (from Jazz Child [High Note], 1999), with Kuhn again playing piano. Her familiarity with the tune allows her to stretch the pitches more than she did almost 20 years earlier, and the later version has a long, impeccable scat section, fully realizing the promise of the original.

Her other recordings as a leader, especially her collaborations with bassists Arild Andersen, Cameron Brown, and Harvie S., are gems, and each contains something special that adds another facet to her rich legacy.

The last recommendation I can make is something that brings me to tears when Sheila Jordan performs it live, and it delivers an equally exquisite impact in recorded form. Live at Mezzrow (Cellar Live, 2022), with pianist Alan Broadbent and bassist Harvie S., is her most recent recording of the tune, one that expresses her personal philosophy as succinctly as a song can: “Look for the Silver Lining” by Jerome Kern and Buddy DeSylva. Her voice has aged, but there is a lifetime of wisdom in every word.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Agreed! I’m still grateful I got to hear Ella Fitzgerald and Benny Goodman (not together) when I was just an early teen. I hope there are some kids in the audience for these performances.