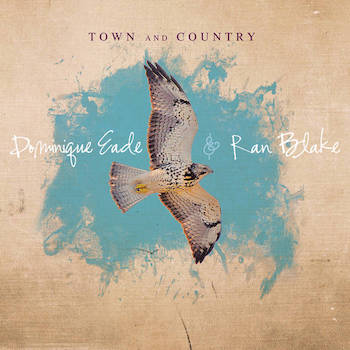

Jazz CD Review: Dominique Eade and Ran Blake’s Personal Vision of Americana on “Town and Country”

Every song here trades in darkness and light — conveyed in Ran Blake’s dynamic shifts, uncanny chord voicings, a ghostly after-image created by the damper pedal on the keyboard, or by Dominique Eade’s clear-eyed emotionalism.

Dominique Eade and Ran Blake celebrate the release of Town and Country at Thelonious Monkfish, in Cambridge, MA., on July 22 at 2 p.m.

By Jon Garelick

“Hush little one, hush,” Dominique Eade sings in the opening line Town and Country, of her new duo album with Ran Blake. The wave-like melismas and gentle vibrato in Eade’s delivery suggest the heart of the African-American blues tradition. But this is no blues-era standard. Eade repeats that first line modulating up — a non-blues progression – and then the line, “Morning soon will light your pillow.” Then Blake enters with some spare single-note piano accompaniment, slightly off-kilter, a shade dissonant. The promise of morning can’t come soon enough, and despite Eade’s consolation, this benediction is no easy promise of untroubled sleep.

In fact, the piece, with that one chord suggesting a link between ancient blues and the learned stylings of the Great American Songbook, is by Walter Schumann, for the score to Charles Laughton’s poison-pill fairytale film noir, The Night of the Hunter (1955). It’s matched, several tracks later, with an even more unsettling nursery rhyme number from the film, “Pretty Fly.”

That’s the kind of musical dreamscape Eade and Blake are going for in this relatively short (48-minute) 18-track CD — unsettled, laced with trepidation, where love and consolation are shaded by apprehension and grief. It’s intended, Eade says in the press notes, to look at American history through the lens of American song, as a way to reflect on this particular historical moment.

The songs are split roughly between Eade’s choice of folk songs, some Blake originals and noir-related material, and the kind of Great American Songbook standards that have been touchstones in their collaborations. (Their previous duo album was 2011’s Whirlpool.)

So there’s a “moon trilogy”: Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Moon River,” Karl Suessdorf and John Blackburn’s “Moonlight in Vermont,” and Will Hudson and George Dunning’s “Moonglow” (paired with the theme of the 1955 movie from which it’s drawn, Picnic directed by Joshua Logan, from the William Inge stage play).

But the throughline of the album is folk — austere, hardscrabble, of the type collected in Harry Smith’s epochal Folkways anthology and celebrated by Greil Marcus as representing “the weird old America” (what he also called “the invisible Republic”). There’s Jean Ritchie’s “West Virginia Mine Disaster,” David Goulder’s “The Easter Tree,” Johnny Cash’s “Give My Love to Rose,” Bob Dylan’s “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” and the spiritual “Elijah Rock.” Even Charles Ives’s resolutely modern “Thoreau” is heard in the context its Transcendentalist namesake, subversive and defiant. In this setting, the Schumann faux folk music is a natural fit. As are the Blake pieces “Moti” and “Gunther,” the latter an improvisation based on a tone row by Blake’s friend and mentor Gunther Schuller.

None of this, of course, is out of place on a Blake album — even the Dylan, though Blake rarely covers anything close to rock music. (The surprise is that the Dylan, with its scorn of consumer culture, was Blake’s choice.) But Blake has always had his own idea of what jazz is and what it can accommodate.

By this point, of course, Blake, now 82, is a legend. He’s been so pretty much since his collaboration with singer Jeanne Lee, “The Newest Sound Around,” released on RCA in 1961, with an endorsement from Schuller. Soon he was helping Schuller bring Third Stream – a combination of jazz and classical – to New England Conservatory but in his own Blakean, category-defying way: folk, blues, gospel, modern classical, or any piece of music Blake loved, could be forged into a single vision. A MacArthur “genius” fellowship eventually followed.

Ever since that first session with Lee (which included some numbers with the bassist George Duvivier), Blake has returned to piano/vocal duos, especially in more recent years, as a kind of default, making multiple albums each with singers Christine Correa, Sara Serpa, and Eade. The duo, of course, is economical, but it also suits Blake’s overall aesthetic of emotional intimacy and noirish drama. It’s his most typical format other than solo piano. There’s nothing quite like the high-wire acts of Blake-and-singer anywhere else in jazz.

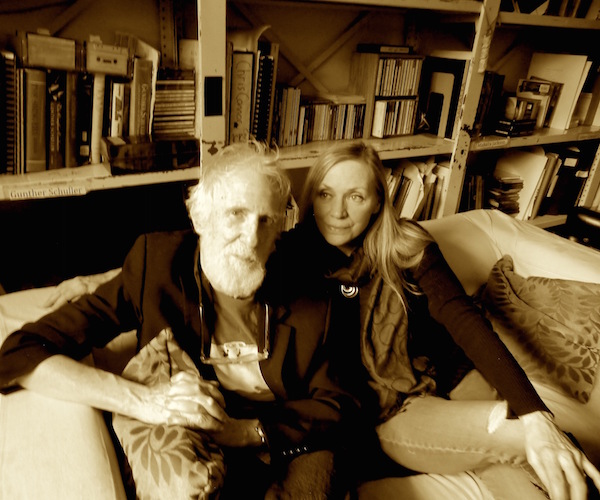

Ran Blake and Dominique Eade. Photo: Ingrid Monson.

Eade met Blake when she began studying at NEC in 1978. The mentor-student relationship has blossomed as the two became collaborators and colleagues (Eade began teaching at the NEC in 1984).

Eade has her own career as a formidable songwriter, arranger, and leader. Her singing has always been known for vocal strength, agility, control, and great sound, as well as interpretive power. But with the first words of “Lullaby,” there’s added burnish and operatic heft, recalling the African-American gospel and spirituals tradition, and adding extra physical gravity. Which makes sense: Eade is 59 now, and voices do typically take on additional weight with age.

But it might also have something to do with the material. Every song here trades in darkness and light — conveyed in Blake’s dynamic shifts, uncanny chord voicings, a ghostly after-image created by the damper pedal on the keyboard, or by Eade’s clear-eyed emotionalism. There are some grim tales here — “West Virginia Mine Disaster” recounts a miner’s last fateful day by a wife or mother (“What can I say to my heart that’s clear broken”), or “Give My Love to Rose,” in which the speaker relates the last words of an escaped convict (“I found him by the railroad track this morning/I could see that he was nearly dead”). Even Leadbelly’s “Goodnight, Irene,” an Americana standard that’s often offered as a cheerful, familiar tune at folk shows, reveals its dark undercurrents (as well as providing the album’s title, with “Sometimes I live in the country/sometimes I live in the town/sometimes I get a great notion/to jump in the river and drown”). Perhaps the most harrowing, and graphic, of these tales is British songwriter David Goulder’s “The Easter Tree,” in which the story of a lynching is told in terms of a hunted rabbit and Christ’s crucifixion, combining folk tale and contemporary social commentary.

There are no easy outs on Town and Country. When Eade sends the last words of “Goodnight, Irene” unaccompanied into the night, “I’ll see you in my dreams,” she’s come full circle from the opening lullaby – and childhood slumber, the sleep of the dead, and the sleep of reason merge in a mythic landscape.

Jon Garelick is a member of The Boston Globe editorial board. A former arts editor at the Boston Phoenix, he writes frequently about jazz for the Globe, The Arts Fuse, and other publications.

This review makes me want to run out and buy the CD!