Classical Album Reviews: Louis Wayne Ballard’s “The Four Moons” and Christopher Rouse’s Symphony No. 6

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Missional zeal from the Fort Smith Symphony and an electrifying performance from the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

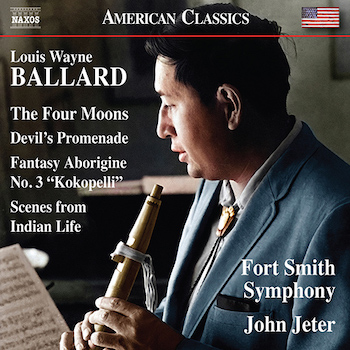

Given the grim, tragic history between Native Americans and Europeans, it’s no surprise that there’s been little meaningful overlap between the respective musical cultures. That fact alone makes John Jeter’s new recording with the Fort Smith Symphony of music by Louis Wayne Ballard significant: Ballard, who died in 2007, was recognized, as the liner notes put it, “as the first Indigenous North American composer of art music.”

What’s more, on the merits of this survey of four of his orchestral works, he was a composer with a strong sense of who he was and what he wanted to say. And he had the technique to get his point across.

Each of the album’s selections draw on Ballard’s Indigenous background.

Devil’s Promenade, whose title references the composer’s birthplace in Oklahoma, is typical: at one point, the score adapts a Sioux Ghost Song and, throughout, it employs an array of Indigenous percussion instruments. The latter turn up, too, in Fantasy Aborigine No. 3, a tone poem referencing Kokopelli, the Native American god of music.

Both of these works are defined by vigorous rhythmic activity and no shortage of colorful scoring. Yet they also evince a wonderful feeling for space — there’s a beautifully atmospheric, almost static episode at the heart of the Fantasy — and an organic sense of motivic and expressive purpose.

The most substantial effort here is the ballet The Four Moons, which Ballard wrote in 1967 as part of celebrations for the 60th anniversary of Oklahoma’s statehood that year. Its plot is built around dances and traditions from four of the state’s important tribes (Shawnee, Choctaw, Osage, Cherokee), and the music is commensurately direct and, often enough, tuneful.

Though parts of the score are decidedly stormy (the middle of the “Osage Variation”) and intense (the “Pas de Quatre”), Ballard’s ear for striking sonorities is at work throughout, from the mellifluous first “Dance of the Four Moons” to the flowing “Cherokee Variation,” with its haunting, short duet for harp and solo cello.

Similarly inviting is the sound world of Scenes from Indian Life, a tetralogy Ballard wrote between 1963 and 1994. The first three movements, which were written first, make the stronger (and considerably shorter) impression, though the concluding “Feast Days” doesn’t want for personality.

Throughout, Jeter and his Fort Smith Symphony play with missional zeal. These are invigorated, impassioned performances, well-balanced, rhythmically alive, and beautifully recorded. That’s just what this music needs — and deserves.

No composer of the post–World War II generation embraced the genre of the symphony better or more enthusiastically than Christopher Rouse. So it’s only fitting that the composer’s valedictory effort (he died in September 2019) be a symphony.

Rouse modeled this work, his Symphony No. 6, on Mahler’s epic Ninth, though he condensed his effort to just about 30 minutes (roughly the same duration as the Mahler’s first movement). There’s no shortage of strong ideas — all thoroughly worked out — in the score, though, in retrospect, its concluding passacaglia might have benefited from a bit of expansion.

No matter, all the essential, Rouse-ian elements are present here: lean, pulsing counterpoint; well-defined rhythmic textures; a kaleidoscopic sound world; vigorous percussion writing; and a shattering coda among them. There’s also a prominent part for flugelhorn, which functions as a kind of totem in the outer movements.

Across it all, there’s a retrospective quality to the writing. The dancing “Piacevole” at times seems to reference the 20th century’s whole symphonic canon. Rouse’s own “Infernal Machine” might drive parts of the “Furioso” movement. The finale ties everything together with rich nobility and, at the very end, a sobering gesture of farewell.

The Symphony was premiered by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra just weeks after the composer’s death, and the present recording, made by those same forces in 2022, bears a commensurate measure of authority. A few muddy, out-of-balance moments in the “Furioso” aside, the ensemble, led by Louis Langrée, delivers an electrifying reading.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.