Music Commentary: “Now and Then” — Nostalgia By and For the Beatles

By Walter Everett

In many ways, “Now and Then” is the fitting gift — a single closing bookend, which Paul McCartney has called the Beatles’ last record.

In February 1981, Paul McCartney was recording in Montserrat with rockabilly star Carl Perkins. There, Carl offered Paul the gift of an observation of their relationship, the newly written song “My Old Friend.” In its chorus, Carl sings, “if we never meet again . . ., my old friend, won’t you think about me every now and then?” On first hearing, the Beatle began weeping and stepped away. His wife, Linda, softly explained to Carl that the last time Paul spoke with John Lennon — shockingly murdered just two months previously — Paul was told, “think about me now and then, my old friend.”

So we can speculate that in January 1994, when Paul heard a composing tape of John’s containing an ode to a departed companion labelled “Now and Then,” the song must have had special meaning for Lennon’s longtime co-writer. This 1977 tape had been given to Paul by John’s widow, Yoko Ono, in response to her having been asked whether John had left any solo recordings behind. The thought was that the three surviving Beatles (Paul, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr) might continue working on one or more of John’s unfinished tunes for possible inclusion in the Beatles’ Anthology project of 1995-96. (It had been something of a fashion to create new recordings incorporating the voices of long-lost artists, often as sentimental virtual duets, such as Natalie Cole’s 1991 additions to her father’s, Nat King Cole’s, forty-year-old hit, “Unforgettable.”) Along with “Now and Then,” the Beatle threesome — henceforth known informally and affectionately as the Threetles — possessed as well three of Lennon’s other home demo recordings — the equivalent of a composer’s sketchbooks, loose jottings made so as not to lose otherwise fleeting unfinished ideas. These other tapes from Lennon’s composing in 1977-1980 included “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love,” both completed under the supervision of Jeff Lynne and released as new Beatles tracks. (A fourth, “Grow Old with Me,” a song based on poems by Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, was left untouched by Paul, George, and Ringo, likely because Yoko had released the demo itself in 1984.)

In those 1995 sessions, Paul, George, and Ringo added new instrumental and vocal parts to John’s vocal/piano sketches, sometimes adding new lyrics and even a new bridge or guitar solo, making use of the day’s digital technology to create seamless compositions out of originally half-finished ideas. But the tech of the times did not enable the reduction of annoying hiss and abrasive hum from John’s offhand cassette tape of “Now and Then,” also marred by a vocal that was half-buried amidst banging on a piano. The Threetles spent a few hours attempting various augmentations to the track, but the undertaking was vetoed by Harrison, who it’s said may have had issues with the song’s compositional integrity as well as its irredeemable sonics.

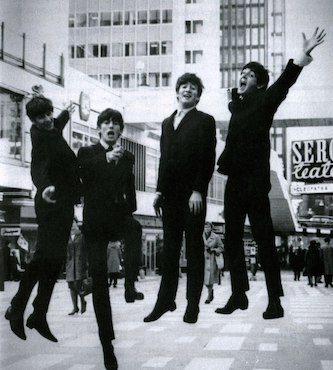

The Beatles in 1963. Photo: Wiki Common

Some two and a half decades later, enter MAL, an artificial-intelligence program created by Peter Jackson’s film company for the production of the eight-hour documentary, The Beatles: Get Back. MAL was the acronym of Machine-Assisted Learning, a label offering nods to longtime Beatle assistant Mal Evans, and to HAL 9000, the Frankenstinian evil-genius computer of 2001: A Space Odyssey. With MAL, Jackson’s team could “teach” a digital audio workstation how to recognize and separate recordings of singing from simultaneous conversation, and even how to do the same with once-combined vocal and instrumental tracks, enabling the scrubbing and sonic coloring of then-enshrouded but now-isolated individual musical components. McCartney realized that Lennon’s garbled voice, piano, and extraneous noise in “Now and Then” were now available as if freshly and properly recorded in a sound studio.

In June 2023, Paul announced to the world that John’s vocal had been extracted from a home demo as the basis for a new Beatles recording enabled by AI, Artificial Intelligence. International conjecture immediately fed anxieties about John’s voice being recreated ex nihilo and of a malware production full of machine-composed lyrics and melodies, resulting in Lennon’s “singing” a song that he’d never imagined. (Anyone exposed to chatGPT “essays” would appreciate such apprehension!) McCartney backtracked a bit, clarifying that the computer did not write the song, that “nothing has been artificially or synthetically created. It’s all real and we all play on it.”

In 2023, not only were Lennon’s original parts available, but so was the Threetles’ work from 1995. Surviving Beatles McCartney and Starr (Harrison having passed in 2001) worked separately to complete the recording, Paul “flying in” his parts from his southern-England studio, Ringo doing the same from Los Angeles, all under the supervision of Giles Martin, son of the Beatles’ producer George Martin and himself the supervisor of new Beatle productions since 2006. After new instrumental ideas were recorded on top of Lennon’s vocal, backing “aah” vocalizations were cribbed from fragments of Beatle recordings “Eleanor Rigby,” “Here, There and Everywhere,” and “Because,” the last being the most noticeable in the finished product. As a finishing touch, string parts reminiscent of the Beatles’ middle years (“Rigby,” “I Am the Walrus”) written by McCartney, Martin, and Ben Foster, were added, these parts recorded in Hollywood’s Capitol Studios. All told, we hear McCartney’s polished piano (replacing the part once loosely taped by Lennon), his Höfner (the old “Beatle bass”), his lap-steel guitar solo (producing a stylish articulation as homage to Harrison’s slide technique), his electric harpsichord (the novelty keyboard once heard on “Because”), and his maracas; Harrison’s electric and acoustic rhythm guitar parts from 1995; Starr’s drums, tambourine, and maracas; vocals by all; and six violins, four violas, three celli and a string bass, all supporting John Lennon’s lead vocal from 1977.

In addition to the supplement of new parts, a key decision was made to delete Lennon’s half-composed bridge, a G-minor passage that comes off as tonally rambling in the overarching A-minor context. Pretty as was its potential, its excision gives the song a newly tightened focus without any loss of its longing, yearning effect (as most, but not all, listeners seem to agree). Deemed blasphemous by some Lennon die-hards, the removal was the kind of thing often done in other work by the composer himself. Many of Lennon’s late-’70s demos reveal that he would cannibalize one section of a song-in-progress and add it to another partial sketch. And certainly the living, breathing, Lennon-McCartney collaboration bore fruit in the ’60s when one of the two would create a new section for the other’s partly written song, as with Lennon’s having contributed the middle section of McCartney’s “Michelle,” or vice-versa in “A Day in the Life.”

In addition to the supplement of new parts, a key decision was made to delete Lennon’s half-composed bridge, a G-minor passage that comes off as tonally rambling in the overarching A-minor context. Pretty as was its potential, its excision gives the song a newly tightened focus without any loss of its longing, yearning effect (as most, but not all, listeners seem to agree). Deemed blasphemous by some Lennon die-hards, the removal was the kind of thing often done in other work by the composer himself. Many of Lennon’s late-’70s demos reveal that he would cannibalize one section of a song-in-progress and add it to another partial sketch. And certainly the living, breathing, Lennon-McCartney collaboration bore fruit in the ’60s when one of the two would create a new section for the other’s partly written song, as with Lennon’s having contributed the middle section of McCartney’s “Michelle,” or vice-versa in “A Day in the Life.”

Another result of the bridge’s eradication was the loss of a strong suggestion that the song was meant to address a departing or lost romantic partner. This change makes the companionship theme more universal, one that might encompass a unity among the divergent worlds of all four ex-Beatles, or even those of Lennon and McCartney alone, whose relationship was once the subject of the late-Beatles’ wistful homeward-bound track, “Two of Us” (initially inspired by Paul’s and Linda’s relationship). In sharing “Now and Then” vocals, Paul and John evoke the good old days, especially by singing in unison through the verse, right up to its cadence where the two diverge in pitch (at “of you” and then at “love you”), as done sixty years earlier (at “HAND!”) in “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” an early example of a Beatles “togetherness” song. Rather than a love song per se, we have the same sort of nostalgia for old friendships also at the core of Lennon’s celebrated Beatle song, “In My Life,” but touched with the minor-mode regretful tone (but not anger) of his “I’m Losing You.”

Another interesting aspect of the 2023 production is that the typically domineering McCartney takes an uncharacteristic back seat, fully complementing Lennon’s message rather than opposing it with a counterpoint of his own, differing, perspective. Paul plays his roundly supportive Höfner with restraint, instead of stealing the spotlight with a bright and intricate bass line on his Rickenbacker. He declines to supply a higher descant vocal melody to accompany Lennon’s verse, thus yielding to John’s prominence. By performing a guitar solo in direct remembrance of George, Paul compensates for his years of slighting the contributions of the youngest Beatle. Paul can be heard, but it’s a Lennon track with an equal balance of reciprocal sidemen.

The first photo taken of The Beatles reunion (1994). The Lost Media Wiki

“Now and Then” has been introduced through carefully staged publicity; the date of the impending release of newly remastered and enlarged Red (1962-1966) and Blue (1967-1970) compilation CDs, featuring the new track, was announced in late October 2023. Jackson’s twelve-minute documentary on the song’s history was released on the first of November. The track itself became available for streaming the next day, and the day after that we got Jackson’s official music video, which supports the song with a brilliant montage of images taken from throughout the Beatles’ career, making clear in its juxtaposition of Lennon’s clownish moments against more somber poses that the track should be accepted as a loving reliving of all aspects of the greatest musical force of the ’60s, rather than simply as a sad devotion to a lost lover. In many ways, “Now and Then” is the fitting gift — a single closing bookend for what McCartney has called the Beatles’ last record.

Walter Everett is author of Sex and Gender in Pop/Rock Music, just launched this summer, and also the two-volume set, The Beatles as Musicians, The Foundations of Rock, and What Goes On. Everett is Professor Emeritus of Music at the University of Michigan and a faculty member at RPM School (rpm-school.com).

Tagged: "Now and Then", George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr

The impact of this Beatles record is attributable to the emotional connection the group has with the culture, which is pretty extraordinary. I believe “Now and Then” will take its place among the minor efforts of the group. Such is also the case in the Nat and Natalie Cole recording and others, like pairing Rod Stewart and Ella. Such efforts have nostalgic power and artistically are empty calories. They reflect a desperation on the part of the music industry. People don’t want to pay for music and for 15 years, album sales and music sales have declined. MRC Data, a music-analytics firm says that old songs represent 70 percent of the U.S. music sales.

In terms of AI, you talk about its use as being both inevitable and positive. I demur. It would be ridiculous to say the aesthetic application of AI falls into the life-or-death category of debates surrounding technologies like cloning, gene splicing or nanotechnology. Some of the debate is morally murkier, like using it to indulge nostalgia-but some applications are obviously abhorrent. For example, as used in the streaming cesspool and in general, to avoid having to pay money to flesh and blood musicians. At the very least, let’s consider its use in the Arts with a more skeptical eye.