Classical Album Reviews: “For Clara” and “Bach Minimaliste”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Reviews of Hélène Grimaud’s latest homage to Clara Schumann and La Tempête investigates seeming stylistic overlaps in the music of J.S. Bach, Henryk Górecki, Jehan Alain, Knut Nystedt, and John Adams.

The Robert Schumann-Clara Schumann-Johannes Brahms love triangle has been a popular programming tack, especially of late, as there’s been a resurgence of interest in the various dimensions of Clara’s career (composer, pianist, muse). For Hélène Grimaud, the concept’s nothing new: she trod this ground — and impressively — way back in 2006, assaying Robert’s Piano Concerto, several of Clara’s songs, and some tumultuous Brahms chamber music on Reflections, her fourth Yellow Label release.

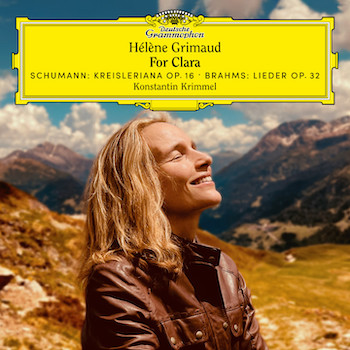

Think of For Clara, then — by my count Grimaud’s 18th album for Deutsche Grammophon — as a long-awaited sequel. True, it’s dedicatee doesn’t show up as a composer. But her spirit hovers over the recording’s program: Robert’s Kreisleriana plus Brahms’s 3 Intermezzi op. 117 and his 9 Lieder op. 32.

Kreisleriana was inspired by Clara — “one of your ideas plays the main role in it,” her future husband wrote cryptically. If audiences and contemporaneous progressives (including Chopin, Liszt, and — yes — Clara) found its technical, formal, and emotional extremes confusing if not off-putting, the eight-movement work has, over two centuries, established itself as one of Schumann’s most visionary.

Grimaud, a pianist whose grasp of the Romantic sensibility (especially the willingness to risk and commit all in pursuit of an artistic goal) is total, has a field day with it here. From the downbeat of the stormy, rhythmically a-blur “Äusserst bewegt,” this is a Kreisleriana that holds nothing back.

Of course, it’s not all sound and fury. The dreamy, inward second half of the third movement’s slow section floats and the balances between the hands in the concluding “Schnell und spielend” are impressively discreet. Though her tone is sometimes a bit steely, Grimaud’s Schumann burns white-hot.

Her Brahms Intermezzi are, conversely, the picture of clarity and warmth, especially the central Andante con moto e con molto espressione, with its haunting sequential progressions and strong sense of shape.

In the op. 32 Lieder, Grimaud proves to be a periodically aggressive accompanist. She doesn’t hold back her volume in the opening number, and in “Der Strom” we again encounter some fleeting issues with balance.

But baritone Konstantin Krimmel holds his own. His singing in these songs about (broadly speaking) love and loss are rich, pure-toned, and clearly enunciated. Whether conveying the furious intensity of “Wehe, so willst du mich wieder” or the ravishing beauty of the closing “Wie bist du, meine Königin,” his partnership with Grimaud is, ultimately, a marriage of equals. In the process, they deliver an unequivocally triumphant account of this strangely neglected song cycle.

Clara, one hopes, would approve.

Once upon a time, divining the origins of Minimalism — or at least of placing them in some longer, historical, Western context — was a popular undertaking among various artists and ensembles. Now, though, the practice is a bit recherché, though, given the right template, it can still be a worthwhile endeavor.

The latest to take up the effort are the period ensemble La Tempête and conductor Simon-Pierre Bestion. Their Bach Minimaliste investigates seeming stylistic overlaps in the music of J.S. Bach, Henryk Górecki, Jehan Alain, Knut Nystedt, and John Adams.

Peculiar as that lineup might appear — and despite the obnoxious practice of chopping up pieces and presenting their movements noncontinously — the disc ends up, for the most part, making its point: the utilization of slowly developing melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic cells that’s one of the foundational characteristics of Minimalism is, in fact, also a basic trait of Western music and its cornerstone, Bach.

True, that’s not exactly news. But it is a fine thing to reflect upon, especially given these selections.

For one, it’s always nice to get a new recording of Adams’s 1977 masterpiece Shaker Loops, even if La Tempête’s reading is a bit broader and more ragged than the composer’s own recording with the Orchestra of St. Luke’s. Regardless, the bass line in “Shaking and Trembling” really rumbles, “Hymning Slews” is hypnotic, and “A Final Shaking” shimmers.

So does Nystedt’s “Immortal Bach,” heard here in both an instrumental and a choral version. Both settings are warm and lush, though the former’s hazy dissonances come across especially well — almost like a blurry dream sequence.

Most of the rest of the disc’s selections are vigorous. That includes two movements from Bach’s Concerto pour Clavecin (BWV 1052) and Górecki’s Harpsichord Concerto.

In the latter, Louis-Noël Bestion de Camboulas makes much of the music’s punching, energetic gestures (especially those in the finale). But he also imbues the first movement with welcome gravitas and a good bit of character (especially as represented in his delicious takes on the music’s slinky melodic turns).

The Bach, of which we get just the outer movements, is crisp and spirited, with strong contrasts between motoric and lyrical spots in the first and a light, dancing character in the last. As a sort of replacement slow movement, Camboulas and Bestion offer an arrangement of the great C-minor Passacaglia (BWV 582), heard in the conductor’s winning adaptation for clavecin and ensemble.

That leaves Alain’s Litanies, which dance freshly and with lots of repetition — but, somehow, very little predictability — and Bach’s Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit. The last is, audibly at least, the album’s biggest thematic stretch. But it’s nevertheless beautifully played and well-directed.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "For Clara", Deutsche Grammophon, Hélène Grimaud, Henryk Górecki, J. S. Bach, Jehan Alain, John Adams, Knut Nystedt, Konstantin Krimmel, La Tempête