Opera Album Review: A Sprightly First Recording of Auber’s Love-Potion Opera

By Ralph P. Locke

Auber’s 1831 “Le Philtre” (“The Love Potion”) is an engaging romp that helped give birth to Donizetti’s “L’elisir d’amore.” Immensely popular in his own day, why isn’t it revived more often?

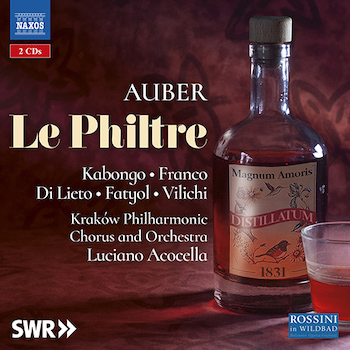

D.-F.-E. Auber: Le Philtre

D.-F.-E. Auber: Le Philtre

Luiza Fatyol (Térézine), Adina Vilichi (Jeannette), Patrick Kabongo (Guillaume), Emmanuel Franco (Joli-Coeur), Eugenio Di Lieto (Fontanarose).

Kraków Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, cond. Luciano Acocella.

Naxos 8.660514-5 [2 CDs] 124 minutes

To purchase or try any track, click here.

Opera lovers are rightly besotted with Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (The Elixir of Love or, more colloquially, The Love Potion; 1832). It is one of the composer’s most frequently performed works, famous for the tenor aria “Una furtiva lagrima.” Its libretto is based on one by the famous French playwright Eugène Scribe.

Well, here is that French libretto (Le Philtre, which means the same thing), as set by Auber and performed at the Paris Opéra the year before. The characters have names (shown in the header) that are mostly different from the ones we’re used to. The Donizetti equivalents are (keeping the order the same as above) the wealthy farm-owner Adina, the more modestly placed Giannetta, the simple but goodhearted farmhand Nemorino, the dashing military sergeant Belcore, and “Doctor” Dulcamara, a seller of phony medicines, including a so-called love potion. In the Auber, the sergeant isn’t quite as smug as he will be the next year in the Donizetti, nor is the Nemorino-equivalent (Guillaume) so touching. Still, the opera works well on its own terms, and I now understand fully how it came to be performed 243 times in Paris between 1831 and 1862.

Because Le Philtre was written for the Paris Opéra, it was required, by administrative fiat, to use sung recitatives rather than passages in spoken dialogue (as was normative at the Opéra-Comique theater). It is also on the short side, as are two other more or less comical operas that managed to receive their first production at the Opéra: Cherubini’s Ali-Baba and Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini. Both of those were relative failures at the time, but their merits have become more apparent in recent decades, thanks in part to first-rate recordings.

The absence of spoken lines makes Le Philtre easier to perform today than many of Auber’s other operas. Singers who are not native French-speakers may be able to sing French clearly and even meaningfully but are often flummoxed by the demands of speaking it.

That the work is all-sung thus makes it particularly well suited to the “Rossini in Wildbad” festival (in the Black Forest region of Germany), where singers from around the world come together to perform less-often-staged operas by Rossini and his contemporaries.

The music is, as so often with Auber, attractive and engaging, in the manner we know as “Rossinian” (though Auber was a decade older than Rossini!), full of shapely vocal lines often sprouting coloratura passages. There is a charming dance-like lilt to many passages, reflected in the frequent use of four-bar phrases. The harmonies are straightforward and often rather predictable. But the orchestra is colorful and varied: Auber knew that he had some of the world’s great instrumentalists at his disposal, and gave them plenty of chances to shine. And there are moments when Auber does something fresh and surprising, as in the developmental middle section of Térézine’s first aria, the weird rising parallel chords as Guillaume drinks the “love potion,” the quick but effective modulations in conversational duets and “differing opinions” finales, or the transition passages that sometimes link the end of a number to the following one, thereby discouraging applause and enhancing continuity. (Applause on this recording has been largely edited out, I’m pleased to say.)

The work contains notable arias for each of the main characters, but it also provides opportunities for the singers to join in duets and in larger gatherings and squabbles. There’s a jolly duet for the quack doctor Fontanarose and Térézine in which he pretends to be an aged Venetian senator and she a female gondolier named Zannetta; she makes clear that she prefers the poor but lovely gondolier Zannetto. (The song thus anticipates Térézine’s preferring lowly Guillaume over the smug sergeant Joli-Coeur.)

Earlier in the opera, the quack gets to babble, just as amusingly as Donizetti’s Dulcamara, about all the (fake) medicines that he is peddling (CD 1, track 12): he calls himself “the friend of humanity” and claims that he is known “throughout the universe and in a thousand other places” for his elixirs, which can kill insects or rats and, equally well, help a widow get over the death of her husband in a week’s time.

A look at the concert performance (i.e., not staged) of Le Philtre by the Rossini in Wildbad festival. Photo: Saskia Krebs

This recording seems to be the work’s first, and it profits from the superb skills of three singers (soprano Luiza Fatyol, tenor Patrick Kabongo, and baritone Emmanuel Franco) who all performed in a recording that I praised here and that was likewise made during the 2019 festival. That work was Meyerbeer’s wonderful Romilda e Costanza, written during the latter’s successful early years in Italy before he relocated to Paris.

Here, as in the Meyerbeer, I am pleased to draw attention to Kabongo, a still-young French citizen who was born and raised in the Democratic Republic of Congo and who then trained in Brussels. His tone is bright and solid, his coloratura fleet and perfectly pitched, and his dramatic instincts straightforward but keen. Let’s hope American opera companies are noticing him. Soprano Luiza Fatayol (from Romania) is, if anything, even more enchanting a vocalist, bringing lots of subtle dramatic touches to her musical numbers. The conductor (from Italy) and the chorus and orchestra (from Poland) are, like the three main singers, the same as in the Romilda, and again fine. New to me, but all highly capable, are the Jeannette (from Romania), the Joli-Coeur (from Mexico), and the Fontanarose (from Italy).

Occasionally, in recitative-like passages, I felt that the text was being sung carefully and too “metrically” — it lacked conversational zip. But a work like this will gain from being done in several productions, until cast members learn how to make each moment sound fresh (as good performers by now do with other once-obscure operas, such as Rossini’s Le Comte Ory, another alternately amusing and touching work first heard at the Opéra. To hear how fruitfully interactive singers can be in an Auber opera, I recommend the classic recording of Fra Diavolo, with French singers plus a very alert Nicolai Gedda, or German-language recordings of Le Cheval de bronze and Le Maçon.

One oddity: it is unfortunate that the name of the heroine, Térézine, sounds like the Czech name of Theresienstadt, the infamous scrubbed-clean ghetto and concentration camp that the Nazis built to display to international authorities their “generosity” to the Jews. Perhaps the producers should have tweaked the name a bit: say, Térézette. (The opera takes place in Basque country in southwestern France: specifically in Mauléon-Armagnac, by the river Adour.)

A look at the concert performance (i.e., not staged) of Le Philtre by the Rossini in Wildbad festival. Photo: Saskia Krebs

I was happy that my first encounter with Le Philtre was through this lively and stylish concert performance (i.e., it was unstaged and uncostumed, though it’s clear from the recording that the singers clearly interacted in lively fashion). The acoustics are quite fine, despite the fact that the name of the venue (Offene Halle: Open Hall) suggests that the space is at best only partially enclosed (a roof but no walls other than behind the performers?).

The French libretto is available online, alas without translation. I’m not complaining only on behalf of native English-speakers. What about all those music lovers in Sweden, Brazil, or Japan who can likely read English capably but not French?

Fortunately, the booklet’s detailed synopsis, with track numbers, will help non-Francophones follow pretty well. The informative essay by Paolo Fabbri is reliably translated, except for one sentence that, as rendered, suggests that Rossini wrote operas after 1831. His last, Guillaume Tell, was in 1829.

I don’t understand why Auber, immensely popular in its time, doesn’t get revived more often. I hope that DVDs and streaming will bring us more staged performances of his works, preferably rendered with as much spirit and precision as are shown here.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.