Jazz Album Review: Terell Stafford’s “Between Two Worlds” — A Spirited Rejoinder

By Michael Ullman

Trumpeter Terell Stafford never seems to be straining; he can be exuberant without sounding brassy.

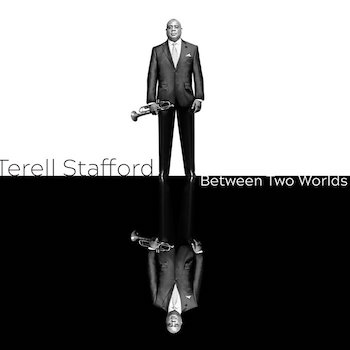

Terell Stafford, Between Two Worlds (Le Coq Records)

Trumpeter Terell Stafford’s Between Two Worlds was recorded at the Village Vanguard in July, 2020 under the strangest of circumstances. The set was broadcast, but, thanks to Covid, there was no live audience. Stafford comments: “It really impacted me emotionally and spiritually. Driving into an empty city with no traffic to make music at a time when the world was shut down was mind blowing to me.” It’s no wonder that the set started with Victor Lewis’s “Between Two Worlds.” I don’t know where the title came from, but it reminded this scholar of the most famous lines from Matthew Arnold’s Victorian-era poem about his visit to the austere Alpine monastery, the Grande Chartreuse. Unlike the pale, self-sacrificing monks he observed, he had lost his faith, and describes himself as: “Wandering between two worlds, one dead, /The other powerless to be born,/ With nowhere yet to rest my head.” “Like these,” he says of the monks who sleep in their coffins, “on earth I wait forlorn.”

Happily, Stafford found solace and even enrichment in these years. Previously he had been on the road constantly. In 2020 and beyond, he was home with his young daughter, whose entrancing being is celebrated on Between Two Worlds in Stafford’s composition “Mi a Mia.” He sounds positively grateful for the forced hiatus: “I got to know my family. I got two years to really get to know my daughter and to establish a real relationship. Before the pandemic working was just part of my DNA. I would just accept everything and make it work. Now I make sure that everything I say ‘yes’ to benefits my family in some way.” Stafford seems to be not only a family man, but a man of unshaken faith. The second number on this new disc is the hymn “Great is Thy Faithfulness” with its lyrics: “Great is Thy faithfulness, O God my Father/There is no shadow of turning with Thee/ Thou changest not, Thy compassions, they fail not.” The treatment of his hymn begins in unexpectedly upbeat fashion, with Alex Acuña’s hand drums, and continues with a repeated figure by pianist Bruce Barth, who sounds a bit like McCoy Tyner, before Stafford’s beautifully rounded statement of the theme. Stafford, who trained in classical music, has an elegant, extroverted tone. There are no Miles-like sputterings or intimate whispers from him. This trumpeter never seems to be straining; he can be exuberant without sounding brassy.

Stafford’s band is equally expressive. He pays tribute to various musical heroes on this album, including Billy Strayhorn, whose gorgeous ballad “Blood Count” was written when Strayhorn was mortally ill and hence between two worlds. Recorded originally by Duke Ellington on the 1967 masterpiece, And His Mother Called Him Bill, here it serves to spotlight bassist David Wong, who plays the unforgettable melody with pianist Bruce Barth in tactful accompaniment. McCoy Tyner’s equally appealing ballad, “You Taught My Heart to Sing,” brings out the best in Stafford. His warm tone and unaffected style are perfectly attuned to Tyner’s under-rated lyricism. Barth, gradually intensifying his solo — block chords alternating with brisk single note lines — re-introduces Stafford for the trumpeter’s second solo.

Horace Silver’s “Room 608” was recorded by the composer in 1954. Another mostly forgotten piece, it’s uptempo, and Stafford’s solo ends with a kind of growl. Then saxophonist Tim Warfield, a long time collaborator with the leader — they recorded together in 2006 — takes over in his typically fluent style. Warfield recorded as a “Tough Young Tenor” in 2006. He sounds emotionally open here: the toughness must have worn off. Drummer Johnathan Blake also solos intensely: this is an all-star group. Bassist Wong sounds like Mingus in his solo introduction to “Wruth’s Blues,” dedicated to Stafford’s mom. (The title seems to combine Ruth and “wroth.”) It’s a slow, funky blues with Warfield playing the first solo gently, avoiding blues cliches. It’s a soulful ending to a spirited set by a group of musicians who might have been discouraged given the shutdown. Instead, Stafford and company made their own world while calling on their ancestors and inspirations.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.