Jazz Album Reviews: Three from the Golden Age of Jazz Recording

By Michael Ullman

Three reissued albums reinforce the claim that jazz recordings hit their peak from 1956 to 1964.

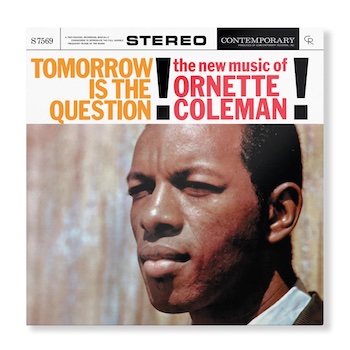

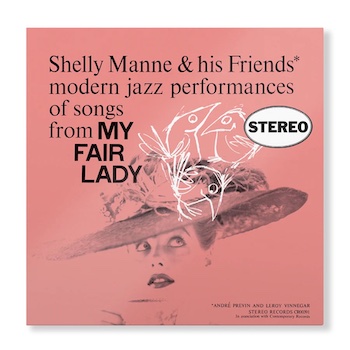

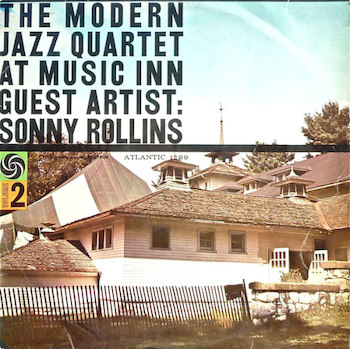

Ornette Coleman: Tomorrow Is the Question (Contemporary, Craft LP); Shelly Manne and Friends: My Fair Lady (Contemporary, Craft LP); The Modern Jazz Quartet at Music Inn/ Volume 2; Guest Artist Sonny Rollins (Atlantic, Mobile Fidelity LP)

“The golden age of jazz recording,” Keith Jarrett opined to me in an interview in his home, “was from 1956 to 1964.” We were trying to figure out what music Jarrett should play to his then young son. I agreed with his assessment. All of the records listed above, for instance, were made in that period. There’s lots of other evidence here to prove the point.

In 1956, Miles Davis staged his marathon recording sessions for Prestige with John Coltrane. (One ensuing LP, Cookin’, is still my favorite.) That year Clifford Brown made his last recordings and Sonny Rollins recorded his Saxophone Colossus and, with Coltrane, Tenor Madness. Monk returned to active playing: remember his recordings At the Five Spot and Thelonious in Action? He made the challenging Brilliant Corners in 1956. Hard bop was happening: Milt Jackson made Plenty, Plenty Soul in 1957; Art Blakey his Moanin’ in 1958. Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy came in 1958, and the Ellington band was revived by the 1956 At Newport recording. Mingus’s Ah Um came along in 1959. Horace Silver recorded his Song for My Father in 1964, at which time Miles Davis, who recorded his ground-breaking Kind of Blue in 1959, was playing with his second great quintet. His ex-pianist, Bill Evans, had already recorded with his most celebrated trio. For those further interested in the cool, Chet Baker was rambling about the country, seemingly making a recording at every stop. These include the quartet with Russ Freeman. And Dave Brubeck’s mega-hit, Time Out, was made in 1959, four years before Stan Getz’s Getz/Gilberto. By 1960, a young jazz musician could play hard-bopping blues and ballads, or so-called modal jazz as Miles demonstrated on “So What.”

That fictive musician might also have been exposed to free jazz by Cecil Taylor or perhaps, as illustrated here, by alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman. Tomorrow Is the Question was recorded in the first three months of 1959 by that daring company Contemporary, which also recorded early Cecil Taylor. The Craft LP reissue is superb, cleaner (of course) than my original. Also, the instruments seem more specifically placed. That’s a bit surprising given that Contemporary records were always beautifully recorded. Both Contemporary records here were remastered from the original tapes by Bernie Grundman, a star in the audiophile world. Tomorrow Is the Question is only the second commercial album by Ornette Coleman, around whom controversy would soon swirl. (Can he even play?)

Yet the music, made with his longtime collaborator Don Cherry, sounds cheerful today, even whimsical, rather than threatening. How can one be intimidated by someone who writes pieces with titles like “Congeniality” and “Focus on Sanity”? The controversy sprang from Coleman’s freedom as a musician, his willingness first to write pieces of eccentric lengths (his “Giggin’” is 13 bars) and then to abandon the road map of chord changes. He would light out for what he (and Huck Finn) called the territory ahead. It seemed strange. Yet Tomorrow Is the Question also contains his best-known early composition, the blues “Turnaround.” Of his lyrical piece “Compassion,” Coleman wrote: It “was written for a piano player who wanted to play, but he had the wrong idea. He seemed to think human emotion and mind were just a matter of environment. He’s wrong, and I had compassion for him.” Coleman was brought up hearing blues and bebop. He proved able to move outside that musical environment. Tomorrow Is the Question is not a mere prelude to Coleman’s significant work. It is an early masterpiece.

Understandably, Les Koenig’s Contemporary Records, which was based in L.A., focused on West Coast musicians: Art Pepper, Hampton Hawes, and Barney Kessel among them. Koenig wasn’t necessarily fishing for hits, but he had some nonetheless. One of the label’s biggest sellers was the jazz version of My Fair Lady by Shelly Manne and his Friends. The friends were pianist André Previn and bassist Leroy Vinnegar. It was recorded in 1956 in the same studio that hosted Ornette Coleman. Coleman was proud of transcending (though, in a subtle way, also incorporating) his musical environment. The message of My Fair Lady and of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion is seemingly the importance of environment. (Cockney is a social class, not a type of person.) My guess is that Manne and crew weren’t thinking of such issues.

Understandably, Les Koenig’s Contemporary Records, which was based in L.A., focused on West Coast musicians: Art Pepper, Hampton Hawes, and Barney Kessel among them. Koenig wasn’t necessarily fishing for hits, but he had some nonetheless. One of the label’s biggest sellers was the jazz version of My Fair Lady by Shelly Manne and his Friends. The friends were pianist André Previn and bassist Leroy Vinnegar. It was recorded in 1956 in the same studio that hosted Ornette Coleman. Coleman was proud of transcending (though, in a subtle way, also incorporating) his musical environment. The message of My Fair Lady and of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion is seemingly the importance of environment. (Cockney is a social class, not a type of person.) My guess is that Manne and crew weren’t thinking of such issues.

Previn said that making the eight pieces on Manne’s My Fair Lady was “a labor of love,” adding “we had a ball making it.” When he was temporarily veering back to jazz playing in the ’80s, I asked Previn what was new in his playing: musically, he said cheerfully, “nothing.” What was new in Manne’s My Fair Lady was the idea of making an entire record dedicated to one musical. It led to dozens of others, including Previn’s West Side Story and more obscure items, such as pianist Teddy Wilson’s Gypsy. How pleasing, though, is the playing here, which includes the sweet lyricism of “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face” and the charming sway of “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly.” The lesser known “Ascot Dance” becomes an uptempo tour de force in which we get to hear Manne, with his usual wit, exchanging fours with Previn. Vinnegar also gets to solo. There are surprises in this unimposing, but thoroughly charming, record: “With a Little Bit of Luck” is rendered as a ballad.

Pianist/composer John Lewis was a key early supporter of Ornette Coleman. He is heard in the Mobile Fidelity reissue of The Modern Jazz Quartet at Music Inn/ Volume 2/ Guest Artist: Sonny Rollins, which was recorded in two sessions during August, 1958. Among the numbers MJQ performs is an intricate arrangement of Charlie Parker’s “Yardbird Suite,” a tune that didn’t need to be gussied up. There’s a ballad medley, and two pieces by John Lewis. To me the highlight of the LP is Milt Jackson’s “Bag’s Groove,” one of two numbers with Rollins. You can hear Jackson heat up as he solos on this untrammeled blues track: at one point, Rollins interjects, “Yeah, baby.” Only the two numbers with Rollins, “Bag’s Groove” and “Night in Tunisia,” are live. One wishes for more, but we get a sense of the power of Rollins in both. Mobile Fidelity records come with fancy packaging: they are well engineered. Listening, you’ll feel like you are in the audience. My only wish, hardly a complaint, is that Percy Heath’s bass would be a little more prominent. But that was a problem with the original recording. The Music Inn sides capture an important, widely popular group at or near their peak.

Pianist/composer John Lewis was a key early supporter of Ornette Coleman. He is heard in the Mobile Fidelity reissue of The Modern Jazz Quartet at Music Inn/ Volume 2/ Guest Artist: Sonny Rollins, which was recorded in two sessions during August, 1958. Among the numbers MJQ performs is an intricate arrangement of Charlie Parker’s “Yardbird Suite,” a tune that didn’t need to be gussied up. There’s a ballad medley, and two pieces by John Lewis. To me the highlight of the LP is Milt Jackson’s “Bag’s Groove,” one of two numbers with Rollins. You can hear Jackson heat up as he solos on this untrammeled blues track: at one point, Rollins interjects, “Yeah, baby.” Only the two numbers with Rollins, “Bag’s Groove” and “Night in Tunisia,” are live. One wishes for more, but we get a sense of the power of Rollins in both. Mobile Fidelity records come with fancy packaging: they are well engineered. Listening, you’ll feel like you are in the audience. My only wish, hardly a complaint, is that Percy Heath’s bass would be a little more prominent. But that was a problem with the original recording. The Music Inn sides capture an important, widely popular group at or near their peak.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: contemporary, Craft, Craft lp, Mobile Fidelity, Ornette Coleman, Shelly Manne

What pleasure to read a bonafide jazz expert offer us a bit of his knowledge. A lovely piece! Sorry you couldn’t hear Percy Heath a little better!