Classical Album Review: “Sam@95” — American Composer Samuel Adler Is Still Going Strong

By Ralph P. Locke

A new CD brings us marvelous and varied works by an American master composed between the ages of 88 and 93 (and a mere child at 55).

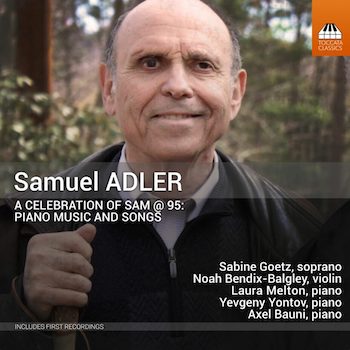

A Celebration of Sam @ 95: Piano Music and Songs

Sabine Goetz, soprano; Noah Bendix-Balgley, violin; Laura Melton, Yevgeny Yontov, and Axel Bauni, piano.

Toccata Classics 686—77 minutes

To purchase or try out a track, click here.

Samuel Adler (b. 1928) is one of the most respected composers and music educators in America, having trained hundreds of composers over many decades at the Eastman School of Music and at the Juilliard School. His books on orchestration and sight-singing are classics, going into multiple revised editions. He writes in all the major genres, and his style is hard to pin down, since he can vary it from piece to piece and movement to movement. In general, it shows similarities to certain pieces by three of his teachers, Walter Piston, Paul Hindemith, and Aaron Copland, but with some of the ferociousness of full-throttle Bartók. (Adler’s fascinating memoir, Building Bridges with Music, is forthcoming in a revised edition. See an enthusiastic and fair-minded review here.)

This CD is the third all-Adler offering in close succession from Toccata Classics (see my reviews of the first, which contained piano-solo and chamber works, and the orchestra-based second). This time, we get a Duo Sonata for two pianos that was written in 1983, plus six works written between 2016 and 2021. Put another way, these works come from when he was 55 in one case and between 88 and 93 for the rest.

“Sam,” as he is universally known, remains in remarkably good health, and I was delighted recently to watch (online) a concert from Eastman and another from Juilliard. Both concerts included very recent works of his. Each was in honor of his 95th birthday and included some onstage remarks by him. Sam is a great raconteur. He enjoyed pointing out to the audience that (referring to the Covid pandemic) it’s not wise to lock a composer in his house: “He’ll compose too much music!”

Most of the pieces on the CD precede the pandemic by a few years. The style shifts a lot, as I hinted above, sometimes even within a movement. What the pieces all have in common is a clarity of gesture and an ability to conjure up a mood instantly and then maintain and nuance it. There are three works for solo piano here: Six Short Occasional Pieces (each of the six movements is dedicated to a musician-friend, such as fellow composer Martin Boykan), Four Choreographies (dancelike pieces, each again bearing a dedication), and Music for the Young (and the Young at Heart): 10 Character Pieces. In all three sets, the movements are on the short side: a few last less than a minute.

Samuel Adler — one of the most respected composers and music educators in America. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

By contrast, the Duo Sonata for two pianos has only three movements but lasts nearly twenty minutes. The first and third movements are full of furious energy (plus some distorted waltzing in the third). The middle movement, “Notturno,” is aptly described in the excellent booklet-essay by retired Eastman musicologist Jürgen Thym (he and I were colleagues there for years) as marked by “meditative calm and emotional depth. Metre and pulse are suspended when a chant-like melody emerges, giving way to a free flow of time.” Here Adler has one pianist strum softly on the strings. This effect was pioneered by Henry Cowell a century ago and has been used notably by George Crumb; in this Adler movement, as Bradford Gowen has noted, the strummed and damped passages “combine strikingly with other colors from the opposite piano played on the keys” (A Performer’s Guide to the Piano Music of Samuel Adler, University of Rochester Press, p. 104).

The other three works are for soprano and piano, and one of them adds a solo violin. (Adler started out as a violinist before he moved into composing, conducting, teaching, and writing.) I found the setting of Maya Angelou’s poem “When Great Trees Fall,” which Adler entitles In Memoriam: RBG (i.e., Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg) very involving and thought-provoking. (I admired RBG enormously, but also feel that she let her ego get in the way by deciding not to retire when she could have been replaced by a younger judge chosen by Barack Obama—that is, by one who shared her lifelong devotion to protecting women’s lives.) Adler has talked about how he and his wife, the noted conductor Emily Freeman Brown, love to read poetry together at the end of the day. One senses his acute responsiveness to verse in the two poems (by Edna St. Vincent Millay and by Thomas Hardy) that he links together as While Listening to Music.

Particularly gripping is Songs of Innocent Love, a four-song cycle to poems by Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger, a Romanian-born Jewish poet who died of typhus at age 18 in a Nazi labor camp. Here Adler adds a violin; indeed, the third song is for soprano and violin without piano. (Adler has a keen sense of how to build variety and drama into a multi-number set or cycle.)

Violinist Noah Bendix-Balgley –his superb control of vibrato and dynamics grabs the ear and heart. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Noah Bendix-Balgley, the North Carolina-born concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, is an astounding performer in the German songs. His superb control of vibrato and dynamics grabs the ear and heart. German-born soprano Sabine Goetz renders the poems in all three vocal works clearly and meaningfully (whether in English or German), though her vibrato is a little slow for my taste, bordering at times on a wobble.

The pianists throughout are remarkably proficient and communicative, showing how Adler, despite his background as a string player, finds ever-new textures on the piano. (For further insights, see Gowen’s aforementioned Performer’s Guide.) I found the ten short pieces for “the young at heart” particularly engaging. They include a waltz, a march, three toccatinas, and a final tango. I can imagine them finding their way onto piano recitals everywhere, side by side with “intermediate”-level pieces by Kabalevsky and Bartók.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Axel Bauni, Laura Melton, Noah Bendix-Balgley, Sabine Goetz, Sam@95, Samuel Adler, Toccata Classics