Book Review: Placing University Branding Irons in the Critical Fire

By Justin Grosslight

Any reader curious about the multifarious and complex relations between academic values and branding will find much to mull over in these essays.

Academic Brands: Distinction in Global Higher Education eds. Mario Biagioli and Madhavi Sunder. Cambridge University Press, 280 pages, £85 ($110).

In today’s media-saturated world, universities are omnipresent, entrenching themselves in contemporary life. The marketing never stops: college paraphernalia now literally covers from cradle to casket. Besides that, there are annual publications of college and university rankings, growing online university programs, a college sports juggernaut, and college admissions scandals that regularly hit the news.

In today’s media-saturated world, universities are omnipresent, entrenching themselves in contemporary life. The marketing never stops: college paraphernalia now literally covers from cradle to casket. Besides that, there are annual publications of college and university rankings, growing online university programs, a college sports juggernaut, and college admissions scandals that regularly hit the news.

But what exactly constitutes an academic brand? And, more importantly, how does university branding impact consumers, insiders, and an institution’s intellectual quest for truth? Academic Brands: Distinction in Global Higher Education critically explores these questions in what is arguably “the first [text] to interrogate university brands as a distinct and influential form of branding.” Writing with welcome interdisciplinary panache, editors Mario Biagioli and Madhavi Sunder, together with scholars of law, business, and sociology, and a journalist, explore how academic branding is not only about logos and trademarked objects, but also is concerned with fostering valuable interactive experiences between institutions and consumers. The goal is for universities to shape and control their identities in today’s “experience economy.” Among the questions this raises: what does branding do to education in a world increasingly governed by images and by manufacturing “unique” academic experiences?

Biagioli and Sunder organize the volume’s essays around three themes. Part I, “Are Academic Brands Distinctive?,” addresses questions of what’s special about university brands, who the producers and consumers are in universities, and to what degree different universities might provide different user experiences. It opens with Biagioli contending that in the effort by institutions to create global recognition, elite universities took up brand mentality years before the corporate sector; they chased student enrollment numbers, sold vacuous “experiences” over pedagogy, solicited donors, and created student brand ambassadors. Looking at British institutions, Celia Lury argues that the crossing of two generic cases — a university seeking an undistinctive type of student and a student seeking a possibly undistinctive university – forms a “personalized generic” as manifested in an enrolled student’s “MyUniversity” platform. Turning to public universities and academic rankings, Deven R. Desai shows how “ranking systems create a trap for schools so that they chase external metrics rather than building programs that differentiate their institution from others.” Whereas most universities focus on a “selection-effect,” or on seeking to admit already attractive and similar student applicants to bolster their rankings, such choices do not fulfill the public university “treatment effect” of helping first-generation and less affluent students improve their lot. Desai lauds UC Merced and UC Santa Barbara’s efforts to assist such students, and the three-tiered University of California system more generally for having diversified goals that helps consumers with various abilities and backgrounds succeed.

Part II, “Local and Global Dimensions,” investigates to what degree distance fortifies universities as academic brands. Paul Schiff Berman argues that, despite the burgeoning growth of global online education programs, the power of university brands remains more local than readers realize. Students still wish to pair their digital learning with at least occasional on-campus visits for resources and discussion. Moving from cultural to juridical analysis, Jeremy N. Sheff contends that one should not view university brands as a matter of legal protections or as primarily about preventing consumer confusion. Rather, one should conceive of universities as “geographical indicators,” which aim to protect local shared history and culture for the purpose of creating and sharing knowledge. Looking more globally, Haochen Sun likens today’s elite universities to hyper luxury brands, noting they fit the definition of a “Veblen good”: product demand increases as the price increases. Few consumers can obtain such academic goods, which are prized heavily for status and networking power. Universities have thus become sites for the well-heeled rather than democratic spaces for broad intellectual betterment.

The essays in Part III, “Conflicting Interests, Haunting Associations,” highlight more insidious branding issues. Mark Bartholomew explores the tensions universities face between supporting their need for partisan branding and their mission to support an unbiased quest for truth. Sadly, branding turns out to be surprisingly uniform: universities deliver similar messages intended to titillate homogeneous consumer desires. Joshua Hunt’s essay offers powerful evidence of the abuse of branding, the devolution into propaganda for the sake of maximizing profit. The University of Oregon turned to Nike CEO and alumnus Phil Knight for support. The result? Nike coopted Oregon staff, trained new communications, public relations, and marketing staff at the university, left the university director of communications in the dark, and encouraged individuals at the university’s Counseling and Testing center to cover up a rape incident committed by three basketball players. Finally, Janet Halley meticulously traces the changing meanings of slaveholder and Harvard Law School (HLS) benefactor Isaac Royall Jr. along with the recently retired Harvard Law School shield, whose design is derived from the Royall family coat of arms. Halley shows how, over time, different audiences (of donors, citizens, scholars, student activists, and faculty) interpreted Royall, his motives, and the HLS shield differently and through a variety of lenses. She concludes that for university branding, “vicissitude is the norm.” If a brand finds itself out of favor with its consumers or on the wrong side of history, its demise could be imminent. Of course, brands also can be resurrected.

Academic Brands comes at an opportune time. Crucial questions about what a university education is supposed to provide, and how much it should cost, are being raised by society at large. Many American colleges are choosing to “optionalize” standardized testing for admission; universities worldwide are reexamining their historical roots; online education is growing; tuition rates are soaring. These challenges are not new. In discussing academia’s move to market values, the spirit of Bill Readings’s classic The University in Ruins (1992) permeates this text, explicitly in Biagioli’s essay and implicitly elsewhere. One of Readings’s major claims is that, as the nation-state waned and universities expanded their audiences, institutions of higher learning would abandon traditional academic and cultural standards to embrace a rhetoric of “excellence,” a vacuous and globalized market-based term whose norms are relative to individual assessors. Yes, universities — especially Anglo-American institutions with “Cultural Studies” programs — have become sites that stand for inclusion, places where members of marginalized communities can have a voice. This begs the question: to what degree are today’s academic standards unsullied by enterprise? Are universities today more about providing belonging for select audiences than pursuing knowledge?

Mario Biagioli, co-editor of Academic Brands. Photo: UCLA

From a legal perspective, I fear that the volume understates a key point. Universities have expanded their repertoire of goods and services beyond traditional pedagogy to include “art museums, technology parks, sports and sports-related merchandising, technology licensing, executive education, hospitals, book publishing, extension courses, distance learning, and so on.” And, just as universities have expanded, so has American trademark law. Amendments to the Lanham Act in 1988 allow for trademark protection, in certain circumstances, of color, shape, smell, or sound. Further, the 1996 Federal Trademark Dilution Act put the enforcement of trademark dilution under federal jurisdiction — enabling legal action even when consumers may not be confused by a trademark. And the 2006 Trademark Dilution Revision Act allows for only a “likelihood” of dilution to be admissible to warrant legal action. This means that universities may be free to attempt to trademark a wide variety of products or items whose qualities achieve “secondary meaning” under their aegis. And they can also try to suppress attempts from those who want to deride, criticize, or mock their institution from the perceived harm of dilution (tarnishment). At their best, intellectual property laws such as these protect trademark holders instead of consumers. At their worst, these laws give universities the power to squelch instances of free speech, limit individual creativity, and control access to educational resources.

I had also expected clearer answers throughout regarding what makes academic brands different from brands at large. Biagioli contends that universities, unlike other kinds of corporations, have traditionally required a fixed place of origin to cultivate user experience. He also contends that university brands don’t just grow through their internal efforts, but by way of outside donor assistance. Further, universities have relied on the marketing of their meaning via students, long before consumers were encouraged to become part of the branding process. (This argument channels Mark Garrett Cooper and John Marx’s thesis in Media U: How the Need to Win Audiences Has Shaped Higher Education (2018) that American research universities have been in the business of audience creation and management since nearly their inception.) Sunder takes a different tack, pointing to three criteria that make academic brands unique: kinship, exclusivity, and sites of reckoning. For me, the first two don’t separate universities from, say, consumer membership at an elite summer camp or special interest club. As for reckoning, few nonacademic brands have the longevity of research universities, the latter elevating universities beyond the realm of conventional branding. Other contributors suggest that universities are in a special cultural/legal category. For example, Bartholomew notes that research universities have massive tax exemptions because of their status as nonprofits; that courts address a variety of employment actions but not tenure decisions; and that patent law has special carve-outs for academic research. Haochen Sun notes that elite universities, unlike luxury brands, are given limited recourse to trademark protection. Still, I remain unconvinced that universities (and their branding) are a radically different species of their own.

Indeed, various essays in this volume suggest that tectonic shifts in universities beginning to embrace a branding ethos occurred in the latter half of the 20th century. Jeremy Sheff notes that, during the late ’70s and early ’80s, universities began methodically branding merchandise, directing trade to preferred vendors. Celia Lury notes that integrated customer information, enhanced by tracking from the mid-’90s, led to a shift in focus from selling products to targeting wealthy customers, who were rated on the lucre suggested by their personal profiles. Customer management was born, a strategy now used by universities via student platforms (among other media). Janet Halley traces the evolution of the Royall/Harvard Law School shield icon from its 1936 adoption until its 2016 removal because of its historical ties to slavery. Yet she notes that, sometime during the late 20th century, “the semiotic register in which it signified shifted from the language of heraldry to that of commercial trademarks.” Even Biagioli finds that MIT course catalogues began depicting images of students on its cover to promote — and constitute — its brand from the ’70s on.

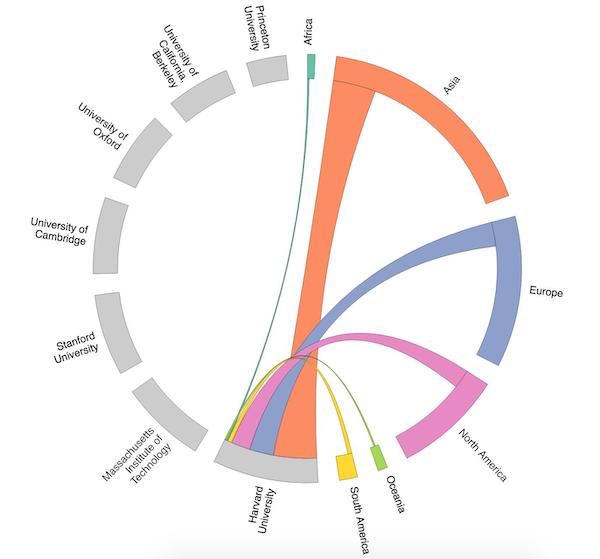

Times Higher Education‘s 2016 ranking of “university superbrands.”

Adopting a branding consciousness, of course, is not unique to universities; rather, it is part and parcel of the American political economy in the late 20th century. As Adam Arvidsson has shown in Brands: Meaning and Value in Media Culture (2006), using product brands to market lifestyle, nourish customer engagement/response, and track customer data became central to many American enterprises. University leaders similarly became concerned with the rise of commoditization. In 1963, then University of California president Clark Kerr warned that university presidents had to balance multiple and potentially conflicting constituencies in his discussion of the “multiversity.” Kerr did not dwell on market forces, but 40 years later, in Universities in The Marketplace: The Commercialization of Higher Education (2003), former Harvard president Derek Bok warned that profit-making interests were encroaching too far on campuses. History suggests that research universities followed in tow with other corporations.

Predictably in edited collections, some essays are more incisive than others. Building on existing research, Joshua Hunt’s essay effectively expands on scholarship that laments how the demands of well-paid, corporate-minded university administrators have displaced faculty goals; here, even administrators have become puppets of a multinational brand. And Deven R. Desai’s examples from UC support Christopher Newfield’s claim in The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them (2016) that privatization and spending on parity features do not entice equality in education. (Though I would have liked to see Desai engage more closely with Cal State and California community college resources. He waxes a bit too rhapsodically about the California system). Meanwhile, Mark Bartholomew’s legal insights are particularly refreshing. More problematically, Paul Schiff Berman’s argument lacks a critical discussion of the efficacy of online learning. Numerous studies have noted the low completion rates for online coursework and, of those who successfully complete classes, many already hold degrees from brick-and-mortar institutions. On top of that, he claims that “most professors, even those reluctant at first, find that teaching online forces them to be more thoughtful and intentional about what they are teaching and what their learning outcomes and methodologies are, and they emerge as better teachers, both online and on campus.” This ipse dixit has neither evidence nor a citation to back it up. I wonder whether a majority of university faculty would concur with this claim.

Madhavi Sunder, co-editor of Academic Brands. Photo: Courtesy of Georgetown University

The volume also could have touched more on how alumni and donors can impact an academic brand. As anthropologist Ajantha Subramanian has shown in The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India (2019), that influence can be significant: American-dwelling graduates of the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), a collection of engineering colleges in India, encouraged their peers to flag IIT on their bios, visibly nourished pan-IIT institutional kinship, established a Pan IIT Alumni Association, and generated positive media coverage for their schools. Each of these actions etched the IITs into white-collar American consciousness. Of course, such behavior was seeded by student coordination to maximize IIT alumni placement in American graduate schools and later by promoting a now-entrepreneurial dream that, like in Silicon Valley, one can flourish economically and with little startup capital. Of course, that ideal challenges India’s socialist inflections and structural stagnation despite India proclaiming itself to be a democracy. That said, it would be interesting to see how academic branding works for universities in nondemocratic contexts. For example, how might elite universities like Peking University or Tsinghua University build brands — given that the Chinese Communist Party wishes to control significant aspects of their functioning? What about non-Western institutions at large? Or lower-tier nonprofit universities? Or for-profit “Lower Ed” American universities? These are all interesting examples to consider, but in this volume Biagioli and Sunder focus primarily on elite Anglo-American research universities and American trademark law.

Curiously, the editors’ sentiments about academic branding sit on opposite ends of the spectrum. For Biagioli, academic brands lock schools into a mold that breeds sameness. Competition is increasingly based on numerical metrics, and universities face an “identity crisis” as they expand their services while, at the same time, traditional pedagogical goals evaporate. Ever the optimist, Sunder prefers to see academic branding as a beacon of hope: through marketing, universities provide aesthetic experiences that can help us with “telling and retelling stories of who we are, collectively and individually in a space that matters to us.” It is a way in which students and scholars can find meaning in education, a part of their quest to build meaningful lives.

Yet just as the editors feel conflicted over the impact of university brands, so I feel ambivalent about this text. Academic Brands fits squarely in the nascent genre of Critical University Studies, a discourse that addresses the impact of privatization, innovation, labor, student debt, and globalization on academic culture. On one hand, critical discussion of these issues is imperative, both to keep universities honest and to ensure that access to them remains open to ordinary citizens. On the other, so much scholarly concentration on the state of higher education troubles me. Don’t scholars have anything more significant to write about than problems within the ivory tower?

Still, Academic Brands successfully addresses many of the contemporary issues haunting today’s (primarily American) universities. This medley of theoretical, concrete, legal, and cultural reflections makes for a dynamic read. Luckily, the editors have supported the book’s online publication — and the public interest — through Open Access on Cambridge Core, which defrays the cost of purchasing an expensive Cambridge University Press text. Any reader curious about the multifarious and complex relations between academic values and branding will find much to mull over in these essays.

Justin Grosslight is an academic entrepreneur interested in examining relationships between science, society, and business. He has published academic articles in mathematics and history of science, book reviews on a wide range of topics, and several vocabulary development and test preparation books. A graduate of Stanford and Harvard, Justin currently resides in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, working as a consultant and mentor. He has traveled extensively throughout China and to all 11 Southeast Asian nations, as well as through parts of Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania.