Visual Arts Review: At the Met in New York — A Fashion Factory and an Enslaved Assistant to Velásquez

By David D’Arcy

Two exhibitions merit a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art — but soon. Each closes July 16.

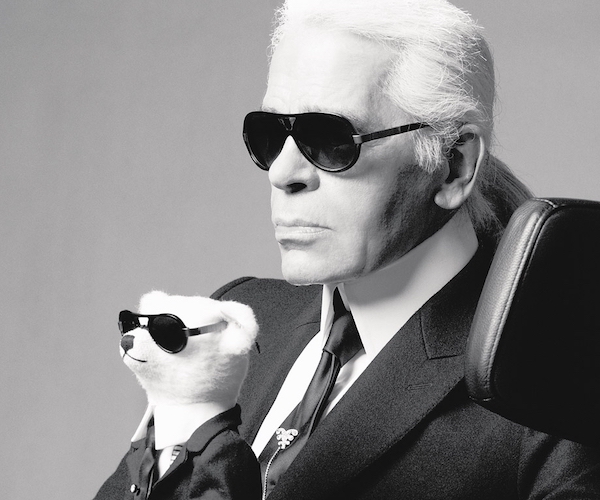

Karl Lagerfeld with white bear. Photo: Karl Lagerfeld Paris Apparel

The designer Karl Lagerfeld (1933-2019), currently being exalted in a retrospective at the Met Museum’s Costume Institute, was a force in fashion for 65 years. He saw his calling as a business, not art. Always claiming to look toward the future, like anyone trying to shape or anticipate taste (although he obsessed over the art nouveau objects that he collected), Lagerfeld scorned the Met as the “Necropolitan Museum of Art.”

That hasn’t stopped the Met from celebrating the influential German with Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty, which seizes on William Hogarth’s reflections on straight and curved lines in The Analysis of Beauty (1723) as an organizing principle to travel through Lagerfeld’s creations. In this case, German rectitude meets the sensuality of Paris, where Lagerfeld lived since his 20s.

Curator Andrew Bolton packs some 180 garments and other objects on top of each other — on two levels, reminiscent of Manhattan parking lots. It’s more inventory than you’ll find on view in most retail stores. An inscription above one portal quotes Lagerfeld: “Fashion does not belong in a museum.”

A designer of everything from sunglasses to shoes, Lagerfeld could draw as fast as anyone — think of a factory feeding a factory. Also note that the exhibition is sponsored by Condé Nast, Chanel, Fendi, and the firm that bears Lagerfeld’s name. Conflict of interest? The designer did say that fashion was a business.

On the Met’s website, Bolton’s narrated guide to this densely packed show, designed by architect Tadao Ando, is erudite and essential. “Kaiser Karl” Lagerfeld emerges from the description as something of a paradox. As we watch him pass (or march) through history, we also watch history pass through him. Lagerfeld was a man who made supreme arrogance his brand, yet he ended up satirizing himself, filling a whole gallery in the exhibition with self-parody, most of it merchandised. “When I was younger I wanted to be a caricaturist. In the end I’ve become a caricature,” he once told an interviewer. Lagerfeld himself leavens this admiring tribute with some much-needed irreverence.

Those who prefer not to wait in line should visit Juan de Pareja: Afro-Hispanic Painter, which also runs through July 16.

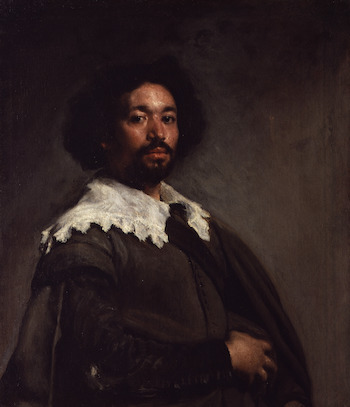

Diego Velásquez, Juan de Pareja, 1608-1670. Photo: courtesy of the Met

Juan de Pareja (1608-1670), the enslaved Black man and subject of the classic portrait by Diego Velásquez (1599-1660, acquired by the Met in 1971), was also a painter. His grand religious canvas The Calling of St. Matthew (1661), loaned by the Prado in Madrid, includes Pareja’s depiction of himself at the left edge of the scene.

The show is structured around two journeys. One trip is by Arturo Schomburg (1874-1938), the Afro-Puerto Rican scholar who traveled to Spain during the ’20s in search of Juan de Pareja’s story. He chronicled the project for The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP. The historian’s collection of books, prints, and documents is the core of the holdings of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library.

The other journey is the visit to Italy by Velásquez and Pareja, then his enslaved assistant, in 1649-51. Velásquez painted Pareja’s portrait there. That work, some say, helped Velásquez obtain a commission to paint Pope Innocent X (a work on view in the show, which was also the subject of a frightening modernization from Francis Bacon). Pareja was granted his freedom (which included a wait of four years, still enslaved, before he could exercise it) and pursued his own painting career, as seen in the galleries.

The groundbreaking show also includes a street scene of three children, one of them African, by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682), himself a slave-owner.

We’re reminded of the racial attitudes in that era by Francisco de Zurbarán’s Battle between Christians and Muslims at El Sotillo (c. 1637–39), in which the Virgin Mary, holding a cherub, intercedes to help Christians on horseback defeat armed Muslims in the 14th century.

Another work inspired by the tensions in Spain between Christians and Muslims, The Redemption of the Captives, a painted and gilded relief in wood from 1599 by Pedro de la Cuadra, depicts the manumission of enslaved European captives by the Mercedarians, an order of priests who bought back the freedom of prisoners held by North African Muslims. The scene is among a number in this exhibition that will be new to most visitors.

The exhibition’s web pages and catalogue reconstruct Spain’s Golden Age with research that dispels centuries of myths about this painter. Who knew? And if that weren’t enough, the works by Velásquez in the show could be a second exhibition.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Andrew Bolton, Juan de Pareja, Karl Lagerfeld, Karl Lagerfeld: A Line of Beauty