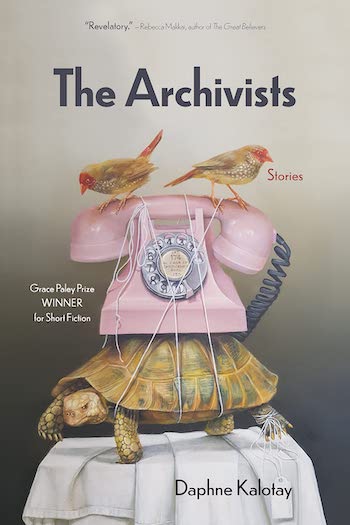

Book Review: Daphne Kalotay’s “The Archivists” — Short Studies in Pervasive Loneliness

By Kai Maristed

Daphne Kalotay’s fresh eye for the outside world is paired with a sympathy for the inner world of her protagonists, which can feel helplessly pained at times.

The Archivists by Daphne Kalotay. Triquarterly, 232 pages, $20 (paperback)

Daphne Kalotay is a classicist, in the grand tradition of the American short story. Fitzgerald, Updike, O’Connor, Cheever, Dubus, Baldwin… those are just a few still immensely readable names on our national shelves. In a sense, the homegrown art of the short form resembles jazz in its combination of craft and discipline with freedom — the freedom that comes from mastery — and high development with cultural rootedness. Surely, in this land of rampant capitalism, the rise and popularity of magazines played a key role. Just as Dickens and Zola lived by writing novels for pennies a line, authors like Fitzgerald flourished on the high rates paid by periodicals for shorts, at least for a couple of decades. The Golden Age! How things have changed, since the Saturday Evening Post stopped buying. Literary magazines, wonderful as they are, cannot pay nearly enough to support a wife in an asylum. Aspiring fiction writers now siloed into pricey MFA programs learn to write by rules, to follow current stylistic fashions (first person present tense, anyone? staccato space-breaks?) and to assume that grubby real-world experience is irrelevant to their goal. That being…?

Daphne Kalotay is a classicist, in the grand tradition of the American short story. Fitzgerald, Updike, O’Connor, Cheever, Dubus, Baldwin… those are just a few still immensely readable names on our national shelves. In a sense, the homegrown art of the short form resembles jazz in its combination of craft and discipline with freedom — the freedom that comes from mastery — and high development with cultural rootedness. Surely, in this land of rampant capitalism, the rise and popularity of magazines played a key role. Just as Dickens and Zola lived by writing novels for pennies a line, authors like Fitzgerald flourished on the high rates paid by periodicals for shorts, at least for a couple of decades. The Golden Age! How things have changed, since the Saturday Evening Post stopped buying. Literary magazines, wonderful as they are, cannot pay nearly enough to support a wife in an asylum. Aspiring fiction writers now siloed into pricey MFA programs learn to write by rules, to follow current stylistic fashions (first person present tense, anyone? staccato space-breaks?) and to assume that grubby real-world experience is irrelevant to their goal. That being…?

Kalotay, in this, her second collection, knows what she’s after. She wrote her dissertation on Mavis Gallant, was a mentee of Saul Bellow, has won multiple prizes and fellowships (Yaddo, Grace Paley Prize, to name only two), and is a lauded teacher (most recently at Princeton University). In short, Kalotay is a writer for the experienced reader. Consider her fresh eye for the passing detail:

“…alarming Christmas cards from friends whose infants appeared to have been replaced, overnight, by pre-pubescent children…”

“In the stub of driveway sat a white van.”

“I made my bewildered students learn the difference between can and may, uninterested and disinterested, lay and lie. To deny the accuracy of one versus the other, I explained, was a first step toward moral corrosion.”

“Two girls with the angular look of models sat narrowly on their stools, like Egyptian cats.”

And my particular favorite: “…cows whose tails spun like dials.”

If these lines make you smile with recognition, you’re likely to enjoy The Archivists. Verisimilitude lies in the specifics of setting: unglamourous neighborhoods around Boston that Kalotay knows like the lines in the palm of her hand. An Eastern European village either seen or imagined with great meticulousness. “Wedged into the cliff walls were stone houses with slab-stone roofs, hand-rigged antennae…It was refreshing to rise away from the street noise and car exhaust, from the church bells clanging like an angry cook rattling copper pots.”

Kalotay’s fresh eye for the outside world is paired with a sympathy for the inner world of her protagonists, which can feel helplessly pained at times. An author’s pity for struggling characters is a common paradox in fiction. After all, she’s the one responsible for their predicaments. All but two of Kalotay’s protagonists are female, mostly 25-40 years old. Defensive, even prickly. They are introduced to us up front and center, and tracked closely to the end.

It’s said that there are three kinds of conflict in fiction: person (if I may) vs another person, person vs nature, and person vs self. The stories in The Archivists belong squarely in the last category. In her longer, more complex story structures — for she is very much a narrative engineer — Kalotay limns the protagonist’s perceived problem as it grows from mote to beam, only to swivel near the end to a revelatory angle of view or fact, exposed weakness or lie, that transforms her understanding and ours.

Author Daphne Kalotay — a narrative engineer. Photo: Sasha Pedro

In The Archivists the source of individual malaise is a deep well of loneliness no matter who else figures in the story, along with chronic self-doubt and second guessing. The leads in these twelve stories also tend to share insecurities about their appearance, and ‘complexes’ about being (or having barely escaped from) what is today euphemistically called the middle class. They are accepters, not fighters. Most feel tethered for one reason or another to undervalued, often insecure jobs such as teachers, a grant writer, a copywriter, etc. They jog, bike, date (not happily), cook, even take an Alpine hiking trip with friends. Life is a predictable stream. “I’d been tamping down my own wants for so many years, I no longer knew what it felt like to hope for something.” And then something happens — something that blows all the repressed doubt and misery out of the water, sky high, to rain down on the main character in a confusion of memory and nascent insights.

And where does the pervasive loneliness come from? A major motif linking these stories is the loss of someone inexpressibly dear. Loss by death, loss by abandonment, the loss of first love in the Holocaust: a future lost. Guilt often plays in, making it hard or impossible for the survivor to move on. They arrived too late, mistook the signs, even inadvertently set the death-trap. In one story, an emotional refugee from divorce willfully (and improbably, to this reader’s mind) invites a chance, ugly death on herself. In another, a forty-five-year-old veteran of “negligent boyfriends,” all quick to decamp, forges an unusual bond that is nearly destroyed by her need to conceal and lie about her thoughts, her flaws, her age.

If this all sounds a little bit gloomy, it can be. The much-praised title story might have been capsized by its parallel narratives of crushing loss, were it not for Kalotay’s wry touches of humor. Here is the human condition, she seems to be saying, in a short-story nutshell. Happily, in other tales the shock-to-epiphany ending often reveals a new possibility, a new direction, like rays of light shining into a heretofore unnoticed path in a dense wood. Taking the next step is up to the main character — and left to our eager imagination.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other papers. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, set in Berlin. Recent work includes “Evangeline, or Theories of Childhood Development,” in the Iowa Review, “The Age of Migration,” in Ploughshares, and a forthcoming essay in Agni. Read Kai’s Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

Terrific review about a wonderful author!

Much appreciated, Mark!