Classical Album Review: Pianist Keith Jarrett and the Music of C.P. E. Bach — A Nice Fit

By Michael Ullman

Keith Jarrett has said that he thinks there is room for C.P.E. Bach recordings on a modern piano. He proves himself right with this 1994 album.

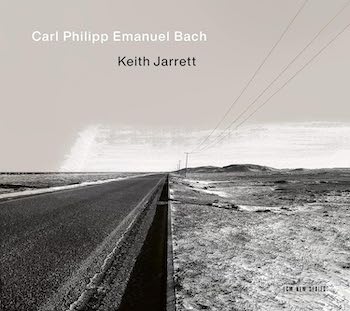

C. P. E. Bach, The Württemberg Sonatas (ECM), Keith Jarrett, piano

Joseph Haydn said of the first six sonatas composed by C.P.E. Bach, the son of J.S. Bach: “I could not leave my clavier until I had played them through. Whoever truly knows my work must recognize that I owe Emanuel Bach very much and that I have diligently studied and understood him.” Mozart said more simply, “He is the father, and we are the children.” More recently, scholars such as the late Charles Rosen have pushed the importance of Emanuel’s compositions and their influence on composers that came after him. Given these impressive accolades, one would think it would be difficult to ignore Emanuel Bach, who lived between 1714 and 1788. But that is what has mostly happened. So Keith Jarrett’s set of the Württemberg Sonatas (1744), composed two years after the Prussian Sonatas that so affected Haydn, is especially welcome, if for no other reason than it will draw new attention to Emanuel Bach’s distinctive music. Jarrett’s versions were recorded nearly three decades ago, and are here issued for the first time by ECM on compact disc and vinyl. (I am listening to a download, however.)

Joseph Haydn said of the first six sonatas composed by C.P.E. Bach, the son of J.S. Bach: “I could not leave my clavier until I had played them through. Whoever truly knows my work must recognize that I owe Emanuel Bach very much and that I have diligently studied and understood him.” Mozart said more simply, “He is the father, and we are the children.” More recently, scholars such as the late Charles Rosen have pushed the importance of Emanuel’s compositions and their influence on composers that came after him. Given these impressive accolades, one would think it would be difficult to ignore Emanuel Bach, who lived between 1714 and 1788. But that is what has mostly happened. So Keith Jarrett’s set of the Württemberg Sonatas (1744), composed two years after the Prussian Sonatas that so affected Haydn, is especially welcome, if for no other reason than it will draw new attention to Emanuel Bach’s distinctive music. Jarrett’s versions were recorded nearly three decades ago, and are here issued for the first time by ECM on compact disc and vinyl. (I am listening to a download, however.)

Scholars tend to pick apart C.P.E. Bach’s works, finding in him traces of the baroque, early classical, and even a foreshadowing of the romantic era. Yet these sonatas sound complete in themselves, and we aren’t likely to be startled by the churning emotions that shocked Bach’s contemporaries. The Württemberg Sonatas were named after one of his students, the Duke Carl Eugen of Württemberg. They were written for clavichord, and have mostly been played on harpsichord. (I recommend what might be the definitive harpsichord recording, Bob Van Asperen (on Teldec). Of course, Jarrett is best known as an improvising pianist who first came to the fore with the Charles Lloyd quartet. He has, nonetheless, recorded classics by J.S. Bach and Handel as well as a particularly beautiful set of Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues. The C.P.E. Bach sonatas seem to be a logical extension of what he had already accomplished in that field. Jarrett has said that he thinks there is room for C.P.E. Bach recordings on a modern piano.

Pianist Keith Jarrett. Photo: Henry Leutwyler/ ECM Records

The pianist proves himself right with this 1994 album. The sonatas come neatly packaged in three movements, with two relatively brisk movements surrounding a slow one, an Adagio or Andante. Bach writes lovely melodies in monophonic pieces that emphasize his intuitive songfulness. His writing also seems to be restless; his compositions seem ready to burst out of their conventional packaging. He is never quite predictable. I am listening to the stately Adagio non molto of the Sonata No. 6 in B Minor six. It begins with a series of dramatic chords. The lovely pages that follow interrupt that stately melody with tripping phrases that sound as if Emanuel were about to whip up one of his dad’s fugues. He doesn’t, of course, but this uncertainty generates, for this listener, a kind of delighted expectation. His lyricism is not that of Mozart: there are no long lines that reflect that kind of melodic genius. Emanuel is his own man.

Jarrett’s playing is nuanced and varied, admittedly in a way a clavichord couldn’t reproduce. He states the beautiful melody of the Adagio in the Sonata No. 2 in A-Flat Major boldly, draws back, and then returns to his initial approach in a convincing manner. It is a touching performance, as is his playing of the Andante in the Sonata No. 4 in B-Flat Major, which begins with single note delineation of the main melody. I don’t know why this recording was withheld for nearly thirty years. Though there have been other excellent recordings of these pieces on pianos since (I admire David Murray’s on Summit), Jarrett’s particular lyrical style fits C.P.E. Bach notably. His recording should attract new listeners to Bach’s second son.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.