Book Review: A Life of Russian Poet Osip Mandelstam — “An Attenuated Voice of Freedom”

By James Kates

The biography is a workmanlike introduction, valuable because it brings a measured understanding to Osip Mandelstam’s life and poetry as well as to the horrific decades he lived through.

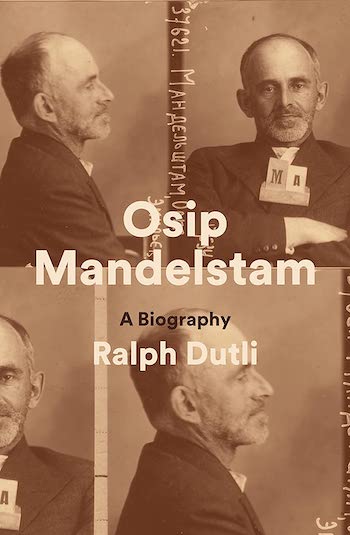

Osip Mandelstam: A Biography, by Ralph Dutli. Translated from the German by Ben Fowkes. Verso, 432 pages, $31.96.

It is generally acknowledged that four great Russian poets dominated — even as they defied in four different ways — the Soviet half-century. Time and the opening of archives have given us a new perspective on these towering figures. Two men, two women, born in successive years from 1889 to 1892, and each with his or her own destiny: Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Boris Pasternak, and Osip Mandelstam.

It is generally acknowledged that four great Russian poets dominated — even as they defied in four different ways — the Soviet half-century. Time and the opening of archives have given us a new perspective on these towering figures. Two men, two women, born in successive years from 1889 to 1892, and each with his or her own destiny: Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Boris Pasternak, and Osip Mandelstam.

Of these four, Mandelstam fell into the role of martyr in a time of purges, a role that has long defined his reputation outside Russia. Arrested in 1934 for having written a nasty poem about Stalin, arrested again in 1937 just because, he died in a transit camp outside Vladivostok in December 1938. (Many of the details were not made public until the 1990s.)

Mandelstam’s wife Nadezhda loved him passionately while he lived, kept his poetry from destruction, and then established his hagiography with two magnificent memoirs, published in English in the 1970s as Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

Since then, Mandelstam’s poems have been translated over and over again into English, with varying success (see https://artsfuse.org/tag/osip-mandelstam/). And now we have a careful new biography of the poet, written in German by Ralph Dutli and translated by Ben Fowkes, based on research that takes advantage of other memoirs as well as new scholarship and documentary revelations after the end of the Soviet Union.

One stated aim of Dutli is to rescue Mandelstam from our foreknowledge of his fate, and to see him as a “joyful, fun-loving poet.” In this he fails spectacularly. Instead, the biographer reinforces a star-crossed destiny predicted by its victim early on.”His desire to share Russia’s fate right up to the bitter end is already evident in a poem written in 1913,” Dutli notes. When he tries to give us instances otherwise, he can come up only with examples like “Mandelstam gave her a poetic ‘wedding present,’ as well as several humorous ditties. But death creeps into one stanza of this bright and cheerful poem: ‘Oaths remain imprinted on our lips / And eyes dash under horses’ hooves to die.'”

That cheeriness aside, the book is a workmanlike introduction, valuable because it brings a measured understanding to Mandelstam’s life and poetry as well as to the horrific decades he lived through.

Mandelstam did not set out to be a martyr. Like nearly everyone else in his society, he suffered terribly through the ’20s and tried to navigate a course of safety through the ’30s, clear-eyed but contrary. “The wolfhound century leaps on my back,” he wrote in 1931, but I have no wolf in my blood … and shall only be killed by my peers.”

Like so many millions of others, he failed. In his case, fate was not completely random. “It is not the punishment that makes the martyr,” Saint Augustine had written, “but the cause.” Mandelstam’s causes were an abhorrence of brute violence and a devotion to the power of words.

Dutli is especially careful untangling Mandelstam’s relationship to his Jewishness, and (not unrelated), to his “cosmopolitan” Europeanness, including a love for an Italy he knew mostly from literature, culminating in a thoughtful engagement with Dante. The poet, who was born into a Jewish family, converted in 1911 in order to be able to study at a university. He embraced many symbols and images of Christianity, and has even been interpreted as writing a cryptic Christian mysticism. But Dutli’s interpretation is more straightforward: “His work is an attempt to unify all the elements of Western and European culture and worship and synthesise them poetically.”

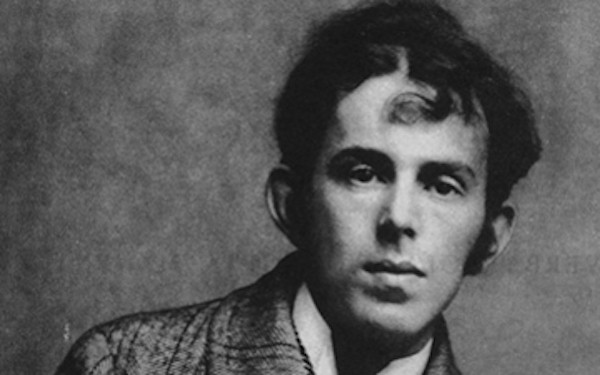

A young Osip Mandelstam.

While Mandelstam’s story has often been refracted through his relationships with his literary contemporaries Akhmatova, Tsvetaeva, and Pasternak, Dutli keeps the focus on the poet himself.

He also devotes two final chapters to the afterlife of the poet and the poems. He takes a fitting and necessary look at the long-suffering Nadezhda, who “spent only nineteen of the eighty-one years of her life by Mandelstam’s side and forty-two years as his widow.” It was she who memorized his poems, saved his manuscripts, and presided over eventual worldwide recognition. That recognition is the subject of the last chapter, titled “Return from the Underground,” an allusion to the Orphic associations that run through Mandelstam’s work.

For those not yet familiar with Mandelstam’s poetry, Dutli’s biography provides a useful primer. For those of us who have come to know the poems and prose little by little over the decades — but who are not specialists — the book will be even more helpful because its historical revelations connect many dots.

“Mandelstam does not need to be portrayed as a legendary saint or a mythical hero,” Dutli justly concludes. “We hear the troubled, timid and attenuated voice of freedom in the voice of a poet who has been imprisoned in a system of compulsion. And the unwavering desire for liberty is still there, right to the end.”

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book of poetry is Places Of Permanent Shade (Accents Publishing) and his newest translation is Sixty Years Selected Poems: 1957-2017, the works of the Russian poet Mikhail Yeryomin.

Only 4? Mayakovsky?