Opera Album Review: “Naughty Saint Vitalis” Targets Celibacy in the Priesthood

By Ralph P. Locke

Swiss composer Richard Flury’s engaging comic opera is a celebration of the life spirit, and a criticism of celibacy as a practice that cramps and distorts an individual’s basic humanity.

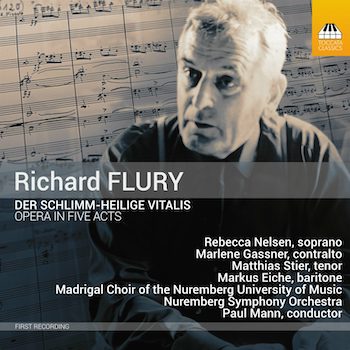

Richard Flury: Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis

Rebecca Nelsen (Jole), Marlene Gassner (Jucunda), Matthias Stier (Vitalis), Markus Eiche (Soldier).

Nuremberg Symphony and Nuremberg University Madrigal Choir, cond. Paul Mann.

Toccata 0632 [2 CDs] 120 minutes

Opera houses through the centuries have often been wary of putting religion on stage. Biblical stories, in particular, were expressly forbidden in many lands. True, beginning in the early 19th century many operas did begin to feature religious figures, ranging from local priests and sacristans to cardinals and other Vatican officials. These figures are sometimes presented in a comical light (Fra Melitone, in Verdi’s La forza del destino), other times in a highly critical one (the repressive Grand Inquistor in that same composer’s Don Carlos).

Opera houses through the centuries have often been wary of putting religion on stage. Biblical stories, in particular, were expressly forbidden in many lands. True, beginning in the early 19th century many operas did begin to feature religious figures, ranging from local priests and sacristans to cardinals and other Vatican officials. These figures are sometimes presented in a comical light (Fra Melitone, in Verdi’s La forza del destino), other times in a highly critical one (the repressive Grand Inquistor in that same composer’s Don Carlos).

But one theme that is rarely addressed directly in opera is the ramifications of the millennia-long requirement within early Christianity and then the Catholic church (though not Protestanism) that the clergy remain celibate. One notable exception is Rossini’s Le Comte Ory (1828), in which the title character (we’re in the 12th century) disguises himself as a religious hermit (in Act 1) and then as a nun (in Act 2) in order to gain entry to the castle of Countess Adèle so that he can attempt to seduce her. (All the men of the castle are away on a crusade to “free” the Holy Land.) The result is delightful, in the manner of a good situation comedy. But, since the title character is not actually celibate, he cannot stand accused of, say, hypocrisy.

In 1962, Swiss composer Richard Flury (1896-1967) completed Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis, an opera that addressed the dangers of celibacy quite directly (and likewise in a largely comical manner), by showing a monk who sings pious hymns and who preaches clean living to a harlot but in fact yearns, if at first only half-consciously, for an active sexual life himself.

I’ve praised, here in the Arts Fuse, two darkly humorous, or humorously dark, operas by Flury: A Florentine Tragedy (after Oscar Wilde, but set in German) and Die helle Nacht. I thus was delighted to be sent recently the world-premiere recording of the last of Flury’s four operas. Indeed, this recording is the work’s first hearing since the original run of nine performances in 1963, the year after it was completed. The libretto, by Franz Johann Danz, derives freely from a novella by the renowned 19th-century Swiss writer Gottfried Keller. The recording was financed by the composer’s son Urs Joseph Flury (who is himself a composer).

***

Why have we not heard of Flury until recently? The standard answer is that he was relatively isolated in the German-speaking city of Solothurn, and probably very busy. He conducted the city orchestra for 30 years, and sometimes led choruses and orchestras in other Swiss cities as well. (Solothurn, in 1950, had scarcely 17,000 citizens. By contrast, a medium-sized city such as Rochester, NY, had over 300,000 that year.)

Another part of the explanation is that, throughout most of the 20th century, composers who continued to write frankly tonal music (even ones who, like Rachmaninoff, were adored by performers and listeners alike) were not taken seriously — especially by academics, but also by some music critics. The prevailing criteria were that music be progressive, experimental, cutting-edge, daring, have an instantly recognizable personal style, and so on.

With the wisdom of hindsight, we can now appreciate the merits of many differing kinds of composing. Ives or Satie were both rather quirky and highly individualistic, and not much performed during most of their career, yet the slightest scrap by each of them is now getting performed and recorded. So why can’t we do some justice to the fully realized operas of a man who quietly did his good work for the art of music but worked in a more traditional style and far from the international limelight? I might also mention that, to Flury’s credit (and unlike his better-known countrymen Arthur Honegger and Othmar Schoeck), he did not have any of his works performed in Nazi Germany. Indeed, he collaborated artistically with Jews and emigrés from other countries. His librettist here, Danz, was a German-speaking Czech who had fled his native land in 1943.

* * *

Soprano Rebecca Nelsen sings the role of Jole. Photo: Lena Kern

OK, back to Der schlimm-heilige Vitalis! The title means something like “Naughty Saint Vitalis” or “Saint Vitalis, That Bad Boy.” Vitalis is an eighth-century Christian monk in Alexandria (Egypt), proud of his piety and his celibacy. He decides to try to lure Jucunda, a sex worker (as she might be called today), away from her trade. But, when he goes to visit her, her place has been taken by the virtuous Jole (pronouned Yo-leh), who is attracted to him. He of course, begins to experience unaccustomed desires (or, rather, unrecognized ones) and even goes through some tortuous spiritual self-examination as a result.

The two women are easy to distinguish on the recording, even without looking at the libretto, because Jole is a lyric soprano and Jucunda a juicy contralto. Vitalis is a tenor; the fourth major character, the unnamed Soldier, is a baritone. Since this is a comic opera, Vitalis ends up finding his (yes) vitality, leaves the monastery, and marries Jole, who is presumably likewise happy not to have to be so pure anymore.

Fortunately, the work turns out to be delightful and pleasantly varied, not least in its many self-enclosed numbers, such as hymns and prayers (in Latin) that the smug monk sings to strengthen his determination, or the joyous wine-festival chorus that opens the final act (out in the public square). Flury’s music here is a fascinating mixture: its style is largely buoyant and High Romantic, such as in some other German comic operas — for example, Die Meistersinger, Hansel and Gretel or parts of Der Rosenkavalier — but with occasional modernist touches in the harmony. The orchestration is far more modest than in Wagner or Strauss, no doubt making it easier for the singers’ voices to come across to the audience. Phrase structure is often relatively square (that is, based on a four-measure norm). But this often applies mainly to the orchestral music, leaving the voices free to declaim the text in phrases of less predictable length, hence more naturally.

You can tell that the cast is strong when such an accomplished singer as Daniel Ochoa — a German-born baritone whose father was from Equatorial Guinea — appears here, magnificently, in the small role of “the Monk” (another monk, not Vitalis). All four of the major roles are well taken. Each of the four gives continuous pleasure yet enunciates so clearly that I could often have written the words down by ear. The chorus (from the university in Nuremberg) likewise sings splendidly.

***

Swiss composer Richard Flury. Why have we not heard of him until recently? Photo: Toccata Records

British conductor Paul Mann, who also prepared the performing edition, worries in his detailed booklet-essay that the work “is likely to be regarded as irredeemably sexist.” Quite the contrary, I’d say: Bad Saint Vitalis is a celebration of the life spirit, and a criticism of celibacy as a practice that cramps and distorts an individual’s basic humanity. Keller, Danz, Flury, and conductor Mann, through their combined efforts, draw our attention to the excesses to which enforced celibacy has often led, including abuses in various religious organizations, such as, in our own day, rampant pedophilia and the systematic effort at covering it up. This opera, like so many others, is at once of its time and still timely. I hope the Toccata recording spurs opera companies — and college opera studios, because the vocal parts are not extraordinarily difficult — to bring this “bad-boy saint” to the stage.

The recording comes with two booklets: one contains several excellent essays; the other, the full libretto in German and English. The libretto is brilliantly translated by Chris Walton, author of the definitive book on the composer, Richard Flury: The Life and Music of a Swiss Romantic (Toccata Press, 2017).

I’ll end with one insight that a wised-up Vitalis makes near the end of the opera: “Doesn’t love delight God, too? Doesn’t it make His heart gentle and forgiving? Doesn’t a husband who is truly tender please His eyes more than does a man who is only halfway Christian [i.e., Vitalis himself when he was not fully committed to keeping his vows of chastity]?”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.