Opera Album Review: A One-Hit Wonder Hits Another One Out of the Park

By Ralph P. Locke

A marvelous first recording of a highly engaging opera by Baroque composer Bernardo Pasquini, known until recently for a single piece: “The Cuckoo.”

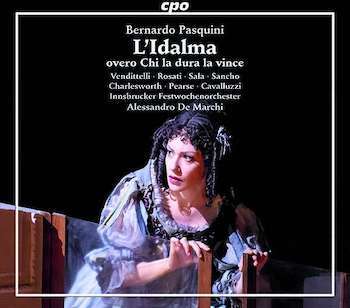

Bernardo Pasquini: L’Idalma

Arianna Vendittelli (Idalma), Anita Rosati (Dorillo), Margherita Maria Sala (Irene), Rupert Charlesworth (Lindoro), Juan Sancho (Celindo), Morgan Pearse (Almiro), Rocco Cavalluzzi (Pantano).

Innsbruck Festival Orchestra, cond. Alesssandro De Marchi.

CPO 555 501-2—190 minutes

To purchase and to listen to any track, click here.

One keyboard piece by Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1710) is widely known: “The Cuckoo,” often played on organ or harpsichord. Ottorino Respighi made a splendiferous arrangement of it in his Ancient Airs and Dances for orchestra. As with other one-hit composers (Tartini, Vitali, Chabrier, Chausson, Humperdinck, Dukas, Orff, Górecki — and, in a way, Samuel Barber), an inquisitive music lover might well be curious to learn what other pieces by him might sound like.

One keyboard piece by Bernardo Pasquini (1637-1710) is widely known: “The Cuckoo,” often played on organ or harpsichord. Ottorino Respighi made a splendiferous arrangement of it in his Ancient Airs and Dances for orchestra. As with other one-hit composers (Tartini, Vitali, Chabrier, Chausson, Humperdinck, Dukas, Orff, Górecki — and, in a way, Samuel Barber), an inquisitive music lover might well be curious to learn what other pieces by him might sound like.

Music historians tell us that Pasquini was an accomplished keyboard virtuoso and a prolific composer of sacred vocal music. He was well employed by the Borghese family, and his operas were performed in Rome and other major cities on the Italian peninsula.

L’Idalma (1680) was first performed in the Capranica family palace, which is located on the piazza in Rome that today bears their name. The booklet essay calls the work “the absolute high point of the commedia per musica genre in Pasquini’s opera oeuvre and perhaps even of the entire music theater of those times.”

A big claim. But I confess to having been consistently delighted with what I heard in this recording, presumably a world premiere, based on the manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. The edition was made by Giovanna Barbati and the conductor, Alessandro De Marchi.

The work zips along, with short arias (some under a minute) and a few duets and trios, and with lively recitatives to set up each of those more formal numbers. A number is usually a single section that may develop one basic musical idea or else will alternate quickly between two or three such ideas, unlike the more formal and expansive da capo arias in two sharply contrasting and self-enclosed sections (ABA) that would soon become more standard in the works of Alessandro Scarlatti, Handel, Vivaldi, and Hasse.

Many of these arias, duets, and trios are accompanied only by the continuo and occur in the midst of a stretch of recitative. Such a passage (which can include voices imitating and overlapping each other) are at first not recognizable as beginning a proper “number” — and indeed, when done, flow right back into regular recitative exchanges. The CDs give track numbers only at the beginning of a scene, making the actual arias and other numbers that much less immediately obvious to a listener, even one who is carefully following the libretto. True, there end up being no fewer than 46 tracks here. If every little formal number had been tracked, the tracklist would have had to go on for pages and pages.

The plot is wacky, with characters changing their feelings and allegiances at a dizzying pace. Briefly, Lindoro — a character apparently based in part on the Don Juan legends — abandons Irene for Idalma (whom he has previously and secretly married) but then tries to return to Irene. Celindo loves Irene, but his love for her and hers for him are thwarted by rumors, misunderstandings, and threats of murder, to all of which the well-intentioned young page Dorillo (a soprano role) inadvertently contributes.

Anita Rosati (Dorillo) in the Innsbruck Festival production of L’Idalma. Photo: Innsbruck Festival

The singers are a largely delightful bunch. Most are quite stylish, their voices firm and flexible. Though some are not Italian-born, they must all have studied the libretto closely: the recitatives are rendered with spit and fire, anger and sorrow, and even some growls and chuckles.

My favorite singers are the two tenors, Rupert Charlesworth (from England) and Juan Sancho (from Spain). Soprano Arianna Vendittelli is sometimes remarkably affecting, though her long notes have a slight slow throb. Baritone Morgan Pearse is mostly a pleasure to the ear, and Anita Rosati — a thin, bright soprano in the pants role of the page Dorillo — always is. The only annoyance comes (as often in early-music recordings) from a bass who lacks steadiness, is labored in coloratura, and packs no punch on low notes (Rocco Cavalluzzi).

Excellent booklet essays and full libretto, all with generally clear translations. The booklet also contains footnotes to explain dozens of mythical allusions in the libretto, and many vivid photos from the staged performances at Innsbruck. I would have liked more explanation about the edition used here: How much had to be added or conjectured?

Juan Sancho (Celindo), Rocco Cavalluzzi (Pantano), Morgan Pearse (Almiro) in the Innsbruck Festival production of L’Idalma. Photo: Innsbruck Festival

I praised De Marchi’s conducting in Paer’s Leonora. Here, too, his tempos seem just right. Also, many colorful instruments are added in appropriate spots, e.g., guitar, woodwinds, or — for Dorillo — tambourine, resulting in quite a colorful and varied “sound picture,” even if you are not following the libretto closely. The eminent British magazine Gramophone agrees: “The zesty performance seldom declines an opportunity to throw in the kitchen sink, including clattering percussion for good measure whenever comic servants are involved.”

If Pasquini’s L’Idalma isn’t the “absolute high point” of music theater from around 1680, it’s certainly close enough. (Other opera composers active from around then or slightly earlier include Cavalli, Cesti, Lully, and Purcell.) If you love Baroque opera, you’d be cuckoo not to give Pasquini a try! And I’ll be delighted if Pasquini now becomes a two- (or more) hit composer! Perhaps the Boston Early Music Festival or some music school might assist in digging up more of his unjustly forgotten works.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical, Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Alesssandro De Marchi, Baroque opera, Bernardo Pasquini, CPO, Innsbruck Festival Orchestra