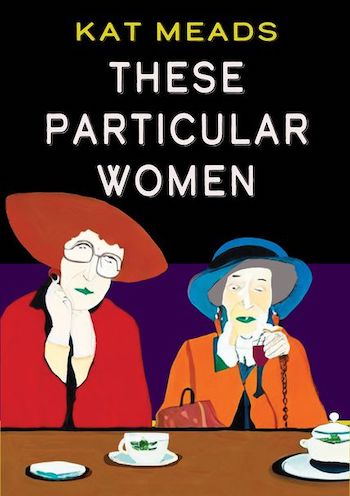

Book Review: Kat Meads’s “These Particular Women” — Celebrating Women Who Misbehave

By Karin Falcone Krieger

Poet, essayist, and novelist Kat Meads puts readers in the presence of women whose lives were often “spectacularly awry.”

These Particular Women by Kat Meads. Sagging Meniscus, 182 pages, $19.95.

Imagine a gathering of the most glamorous, infamous, and rebellious women of the 20th century. That sums up the ambition of Kat Meads’s book-length collection of essays, These Particular Women, which draws a bead on Kitty Oppenheimer, Estelle Faulkner, Lady Caroline Blackwood, Jean Harris, and others. Meads’s mischievous approach is to harvest deep gossip and juicy detail — as well as to make expert use of an often spotty and contradictory historical record — to put readers in the presence of women whose lives were often “spectacularly awry.”

Imagine a gathering of the most glamorous, infamous, and rebellious women of the 20th century. That sums up the ambition of Kat Meads’s book-length collection of essays, These Particular Women, which draws a bead on Kitty Oppenheimer, Estelle Faulkner, Lady Caroline Blackwood, Jean Harris, and others. Meads’s mischievous approach is to harvest deep gossip and juicy detail — as well as to make expert use of an often spotty and contradictory historical record — to put readers in the presence of women whose lives were often “spectacularly awry.”

I first read Meads in 2019 when Dear Dee Dee came out. This wonderfully genre-bending book is a series of letters addressed to a fictional niece, a sort of backhanded autobiography, filled with lots of literary references and scenes with great comic timing. So I approached These Particular Women knowing that I was going to be entertained and challenged. I began the book in the middle, devouring “The Afterlife of Kitty Oppenheimer.” Kitty is the epitome of a Meads woman: disparaged, complicated, unsympathetic, and at the center of a powerful group of people. They love bad men and good cocktails, are bad mothers and not well liked by their contemporaries. Thus they are prone to being erased from history, demoted to the back bench, because of long-lasting grudges and patriarchal indifference.

Kitty’s fourth marriage, to J. Robert Oppenheimer, “father of the atomic bomb,” gives Meads the “Manhattan Project Voices” to draw on. The essay begins with a list of costumes and props the author would include with an imagined Kitty paper doll. Along the way she creates a tiny biography of a figure who has been grievously neglected: “Few would recognize her name or have the opportunity as readers to presume they understood the dips and swerves of her particular personality as posterity records it … characterizations of Kitty on stage and screen are, to date, the characterizations of a lowly supporting player.” Kitty is played by Emily Blunt in director Christopher Nolan’s yet-to-be-released film Oppenheimer. Meads, in her inimitable style, sets out to give us a sense of the woman’s vibrant personality.

In the opener, “Things Woolfian,” Meads reveals her youthful devotion to Virginia Woolf’s writing with an archival image of one of Meads’s college papers, marked up with her (male) professor’s comments. Her commentary grounds us in the prose to come: the kind of sentences that Woolf advocated for in A Room of One’s Own, a female sentence, a sentence that is a “carrier bag” (to quote Ursula Le Guin), where each word and its placement matter as a function of humanity and femininity.

Meads seems to have read everything about each of her subjects: letters, archives, and biographies. She’s noted the films and theater productions where her heroines pop up. Meads snips out the most revealing tidbits from these sources, heaps them up, and builds her indelible paragraphs out of them. In “Things Woolfian,” Meads includes comments on the task of writing biography itself: “Batting away Arnold Zweig’s 1936 request to write his biography, the still alive and kicking Freud thundered: ‘Whoever undertakes to write a biography binds himself to lying, to concealment, to hypocrisy, to flummery and even hiding his own lack of understanding.’” This is Meads’s wry humor at its best, a self-accusatory jest. She ends the essay with a series of “scenes” from Woolf’s life.

Meads’s take on the self-denial necessary for women to be charming is explored in “’Charming (to Some) Estelle’ Faulkner.” After her mother’s death, Jill Faulkner Summers floated this mea culpa for the Southern belle: ‘”Sometimes, I guess, she came on too strong with the charm.” She came on strong but failed to convert every mark, including William Faulkner’s literary-mentor-turned frenemy Phil Stone, who pronounced Estelle “not worth a damn to anybody.” The portrait is built out of juxtaposed opinions and snark about the subject, quotes piled into lengthy sentences, some as long as half a page. But they can be consumed with silken ease. Meads, a Southerner herself, takes on the role of barfly on the wall: who said what about whom behind their backs?

Author Kat Meads

“Which of a writer’s books one picks up first matters. Any further reading will be heavily influenced — if not totally skewed — by that introduction,” Meads perceptively proclaims in “Caroline of Clandeboye.” This essay probes the life of Lady Caroline Blackwood, writer and Guinness beer fortune heiress. Booze and books … What could go wrong?

Meads is a first-wave feminist who has authored over a dozen books in about as many genres over the decades. When Lidia Yuknavich interviewed her in the Rumpus 10 years ago, both were writing historical fiction. (Not the bestselling kind.) Their rebellious female characters — real figures intermingled with the imaginary — refused redemption and disdained likability. The authors discussed how, even in this day and age, they were vilified for writing such unconventional things. Here is a sample of Meads’s defiance in an interview: “Lately, I’ve been reading/re-reading a lot about Zelda Fitzgerald — another Southern gal. In whichever text, when I get to the part where Scott’s dropping her off for lock-in at Highland Hospital, I find myself wanting to pry apart paragraphs in search of the invisible ink passages.”

Zelda does not make an appearance, but These Particular Women is about vindicating women whose independent sensibilities did not align with the eras in which they lived. Their male counterparts engaged in the same behaviors, but they were rewarded for misbehaving. Meads will have none of that hypocrisy and doesn’t feel she needs be earnest or well-mannered either. If this is the first Kat Meads book you read, you will get the right idea of what this rebellious spirit is up to.

Karin Falcone Krieger‘s reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Tupelo Quarterly, LITPUB, Literary Review, Santa Fe Writers Project Quarterly, and other publications.

Tagged: Estelle Faulkner, Jean Harris, Kat Meads, Kitty Oppenheimer, Lady Caroline Blackwood, Sagging Meniscus, These Particular Women