Film Review: Three Shorts Featuring Writer and Activist James Baldwin, Man of the Hour

By Gerald Peary

In these short films James Baldwin does not come off as a relaxed person, someone at ease with himself or quite comfortable in the world. You can feel the acute pain as he speaks.

James Baldwin Abroad: A Program of 3 Films. Directed by Sedat Pakay, Terence Dixon, Horace Ové. Screening at the Coolidge Corner Theatre through March 29.

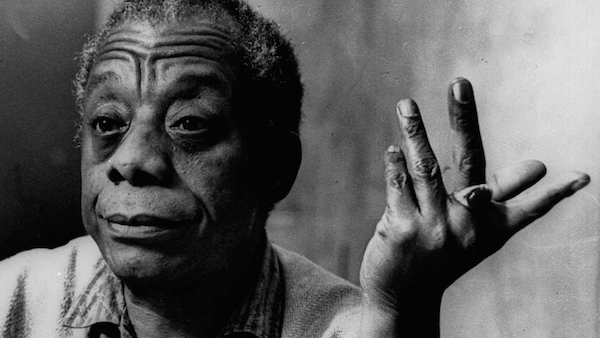

James Baldwin –“The white liberal is the man unwilling to see the forces that created him.” Photo: Wiki Common

James Baldwin (1924-1987) is the man of the hour, heralded by practically everyone these days for the articulate, on-target Black militancy of his fiery collections of essays (Notes of a Native Son, The Fire Next Time) and, in his arresting fiction (Giovanni’s Room, Another Country), for boldly expressing a queer sensibility. He was also that rarity in America: a public intellectual who spoke up with a full voice on the issues of the day. He defended his friend William Styron from Black attacks on The Confessions of Nat Turner. He discussed racial issues on TV with Dick Cavett and famously debated William F. Buckley.

Baldwin was the subject of an excellent 2017 feature documentary, I Am Not Your Negro. Did its considerable success prompt others to go scrambling for buried films featuring the charismatic author? The Coolidge Corner Theatre is now showing three restored Baldwin-centered shorts from 1968 to 1973, each made in a different geographic locale and in different production circumstances and by filmmakers with vastly different points of view. What do these short films have in common? Lots of Baldwin oratory, Baldwin holding forth. My, the man could talk! This was not a relaxed person, someone at ease with himself or quite comfortable in the world. You can feel the acute pain as Baldwin speaks, a Black oracle who experiences the harsh effects of racism in a palpable, inescapable way. Many of his Black friends, he explains, have died early or been murdered. He regards himself, a word-famous writer, as still only steps away from slavery. “I’ve had a hard life, y’all,” Baldwin confesses with a sad grin in one of the films.

Baldwin’s N***** (1968) is explained in a title as “A film record of a discussion at the West Indian Student Centre, London.” Made by Horace Ové, a pioneering British director of color, this is a clearly sympathetic showing of Baldwin delivering an angry, militant talk to a room of left-wing students from Jamaica and other islands who had emigrated to England. “My entry into America was a bill of sale,” Baldwin stands tall and proclaims before the group. “I became Baldwin’s n*****. That’s how I got my name.… I was bred and sold like a mule.” And, shifting tones, becoming darkly ironic, “Whether I like it or not, I am an American…. My frame of reference is George Washington and John Wayne.”

This was 1968, the height of the Vietnam War, and Baldwin accuses the USA, his country, of being “a criminal nation…. Saigon resembles nothing more than the streets of Detroit. In both cities, war is being waged… If freedom is what we care about, we’d be concerned about Johannesburg, Harlem.” Baldwin’s N***** was shot in black and white on 16mm film with just one camera (Gordon Cradock), which holds uninterrupted on Baldwin for his 19-minute opening remarks. Only then is there any cutting, as the event opens up to demanding questions from the audience. Why does Baldwin still use the term “Negro” instead of “Black Man”? Is he for integration or Black Power? What in 50 years does he see to be the position of the Black Man? 90 percent of the audience is Black, but one earnest white man does dare speak and asks, “Is there any place for the white liberal?” Many in the audience shout out, “No!” and Baldwin isn’t any more condoling. “A white liberal is suspect,” he responds. “The white liberal is the man unwilling to see the forces that created him.”

It’s almost 40 minutes into the event when Baldwin gives over the podium to the other Black celebrity in attendance, American comedian-political activist Dick Gregory. Gregory looks down at the now-seated Baldwin and smiles. “My brother James … you are a very groovy speaker.”

Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris (1971). Lots of this film is howlingly funny, certainly not the intention of Terence Dixon, the clueless-beyond-clueless white British director. He yearns to do a literary documentary having Baldwin walking along the Seine discussing himself “as a writer instead of a political figure.” But Baldwin, once on camera, wants of course to speak of racial politics. It’s not four minutes into the documentary that Dixon, this privileged, upper-class twit, starts complaining on the voice track that “Baldwin was quite hostile to me.” Dixon is further thrown when Baldwin brings to the shoot a young Black friend who is contemptuous of the filmmaker and insists they film in front of the Bastille. There, instead of talking about the writing of Go Tell It on the Mountain, its author goes off on urgent Black issues: “My point is the prison is still really here. I’m speaking of my country more than I’m speaking of France. I represent at this moment many political prisoners in America.”

The apoplectic filmmaker doesn’t want to hear Baldwin say, “I’m not so much a writer as a citizen who has to bear witness.” Feeling his documentary being hijacked, Dixon jumps himself on camera and pleads with Baldwin, “What am I doing wrong? Tell me what I’m doing wrong.” Baldwin is exasperated by the stupidity of his interviewer, and pitiless in refusing to capitulate and talk about his books. “My work will speak for itself or it won’t. But I am a Black man in the middle of the century. And I speak for that.”

What a different Baldwin when he retreats to an art gallery run by a Black friend and converses informally with half-a-dozen young African Americans who are staying in Paris. He smiles sweetly when a shy awkward woman tells him how much his books mean to her; Baldwin is deeply moved by a shaved-head dude who says that Another Country is the only book in his life that he’s read cover to cover. And loved it.

In James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973) Turkish filmmaker Sadat Pakay follows the writer about walking through the streets of Istanbul. Baldwin is also seen more intimately climbing out of his bed, walking about in skimpy underpants, changing into a somewhat effeminate robe. Pakay’s agenda is not at all like that of the other two documentaries. He’s there to get Baldwin to spill all about his sexuality. Baldwin isn’t offended to be asked but he answers, “It’s nobody’s business what goes on in anyone’s bedroom. My involvements with men, with women, I say to the world they are not to be talked about. I love a few men, I love a few women.”

Baldwin seems in all these films to be unfailingly honest. But were there really women in his life? Is this nonbinary babble a kind of smoke screen? I am happy to report that Baldwin then goes further, explains more. “I’ve observed that American men are paranoid on the subject of homosexuality,” he says. In addition to the “N” word, he embraced, in 1973, the then daring “H” word. Homosexuality! “It’s there, it’s there,” James Baldwin says, “and it’s been in the world for thousands of years.”

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

Thanks for making me aware of these films. I’ve seen several other docus of the late great James Baldwin, who is always worth watching. Your comment that “Baldwin seems in all these films to be unfailingly honest” is spot on. Unflinching honesty is one of his hallmarks–along with intelligence and a charm that flashes through. These carry through in his writing, as well. At the moment I’m reading his story collection, “Going to Meet the Man”, and marveling at his skill at short fiction, an ability to keep many voices & POVs on the page at the same time.

Thanks, David, for your comments. While reading Baldwin’s short stories, check out “Sonny’s Blues,” perhaps the best story ever written about jazz.