Film Series Preview: “Alice Diop’s Souvenirs of Lost Time”– A Partial Retrospective

By Betsy Sherman

Director Alice Diop’s films explore, with great sensitivity and little sentimentality, the generational effects of colonialism and racism.

Alice Diop’s Souvenirs of Lost Time – A film series at the Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, March 25 & 26, April 10.

French filmmaker Alice Diop. Photo: HFA

The director of one of 2022’s very best films, Saint Omer, will pay a visit to Harvard in April as the recipient of a Gardner Film Study Center Fellowship. Alice Diop will screen and discuss Saint Omer at the Harvard Film Archive on Monday, April 10. A partial retrospective entitled Alice Diop’s Souvenirs of Lost Time will begin on March 25 and 26, and resume with Diop’s visit.

Saint Omer (Arts Fuse review) has won the 44-year-old French filmmaker a slew of awards, including the Grand Jury Prize and Best Fiction Feature Debut at last year’s Venice Film Festival and France’s César award for Best First Feature. She’s hardly a novice, though, having spent 20 years making documentaries. Most of these were set in Parisian suburban communities like the housing project in Aulnay-sous-Bois where she lived until age 10. Diop is the daughter of Senegalese immigrants who moved to France in the ’60s. Her work has explored, with great sensitivity and little sentimentality, the generational effects of colonialism and racism.

Diop co-wrote Saint Omer with novelist and playwright Marie NDiaye and Amrita David (who also edited the film). The movie is a courtroom drama, but uses few of the manipulative tricks of the genre; although it builds into an intense experience, it’s rare among films about sensational trials in that it aims to slow down, rather than speed up, the heart rate of the spectator. This shifts the focus to listening and noticing. The shooting scheme includes many long-duration takes; there’s little camera movement and music is used sparingly.

The real-life event on which Saint Omer is based is the 2016 infanticide case against Fabienne Kabou, an immigrant from Senegal. Diop attended her trial, which took place in the eponymous city not far from the English Channel. Pregnant herself at the time, Diop found that the experience made her question her assumptions about maternity. This moved her to examine the subject as her first fiction film.

Kayije Kagame plays Rama, a novelist and literature professor who is a stand-in for Diop. Rama travels to the northern city to observe the trial, with the intention of linking the crime with the story of Medea. But as she listens to the defendant, here called Laurence Coly (stunningly performed by Guslagie Malanda), she realizes that she won’t be able to tie an academic bow around this instance of infanticide. Another aspect that draws Rama in is the woman’s difficult relationship with her Senegalese mother; it evokes the strain between Rama and her own mother (an immigrant from Senegal), whom we see in the film’s present tense and in flashbacks.

Laurence has been accused of deliberately leaving her 15-month-old daughter on a beach one night, where she would be drowned by the rising tide. Laurence does not deny performing the action: she maintains that a curse had been put on her, which propelled her to that beach with Lili, whom she loved. The defendant is interrogated by a female judge who expresses concern, and a desire to understand.

Kayije Kagame in a scene from Saint Omer.

The scenes that follow Rama when court is not in session provide a brief escape from the institutional setting. There’s an inevitably in Rama’s making contact with a middle-aged African woman who seems to be the only other Black person in town, besides the defendant. She’s Laurence’s mother, who has traveled to France for the trial. Over lunch, she guesses correctly that Rama is pregnant (the four-month pregnancy doesn’t show yet).

Among the witnesses is Luc, the much older white man with whom Laurence has had a complicated live-in relationship. He had been financing her studies in philosophy, as she was working toward a doctorate. He was the father of the little girl, although Laurence kept the pregnancy a secret for months and gave birth by herself at home when he was out of town.

Diop strove to honor the real events in her fictionalization. She and her co-writers used the actual transcript as dialogue, with Laurence speaking the French language in the same formal, dry manner as did Kabou (the character says her mother forbade her from speaking Wolof and wanted her French to be perfect). These testimony monologues are the compelling core of the film, with Malanda conveying stillness and preternatural self-possession (the actress learned tai chi to prepare for the role). The brown short-sleeved cardigan she wears and her skin color make her blend in with the wood of the walls, suggesting her invisibility in the legal arena. There are shots in which she looks swallowed up by the dock. But she has a trenchant gaze, ringed by eyeliner, when she turns toward Rama in the gallery.

After the last of the testimony is given, Laurence’s white female defense attorney sums up, attempting to make sense to the jury of a story that one character says can’t be explained to Westerners. Rama, shaken by her identification with the accused, sorts out the insights it has given her into her own relationships. The voice of Nina Simone stanches the wound as the movie concludes.

A scene from the 2021 documentary, We / Nous.

The Diop series starts on Saturday, March 25, with the feature-length We / Nous (2021). For the documentary, Diop and her crew explored life in the proximity of the RER rail system’s B line, which slices through Paris and covers suburbs (the “banlieu”) to the north and south. Shots of trains and rail yards link the episodes, which vary in style and tone. There’s time spent with an auto mechanic from Mali who lives in his van and feels the cold of France in ways figurative as well as literal; traditionalist Catholics attending a mass in memory of Louis XVI; a nurse (Diop’s sister) who visits the homes of elderly patients, some of whom chat to the camera; an old-school fancy-dress deer hunt; a Holocaust museum; essayist Pierre Bergounioux; and a group of Black teen girls talking amongst themselves.

Diop’s family story is related as well, since she has lived by the rail line. She speaks in voice-over of the mother who died when Alice was a teenager, and whose image she has trouble remembering (an old home movie is a touchstone for her). The director includes some wonderful footage she shot years earlier, interviewing her father about how he made a new life for himself in France. With a patchwork of cultures shown in the film, some separated by persistent borderlines, the question of who the we is, regarding the French people, is left for the viewer to ponder.

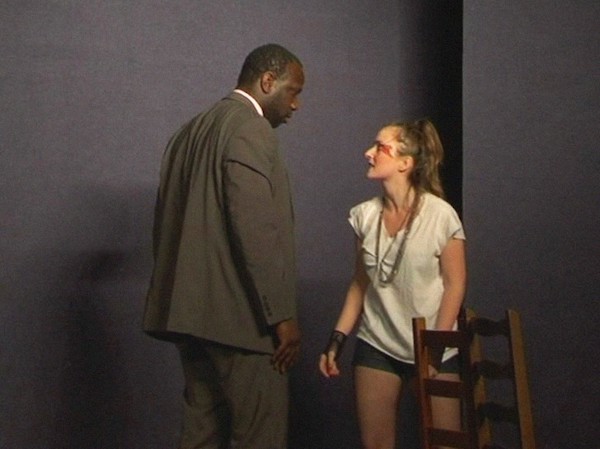

A scene from the 2011 documentary Danton’s Death. Photo: HFA

The series continues on Sunday with two shorter documentaries. The 64-minute Danton’s Death / La mort de Danton (2011), which follows a Black actor struggling to make it in Paris, wasn’t available for preview, but the 38-minute Towards Tenderness / Vers la tendress (2016) is arguably worth the price of admission.

The film is made up of the voices and images of African and Arab young men from a working-class suburban neighborhood. The first speaker with whom Diop converses about love is blunt in his opinions and his vocabulary. Using a derogatory word for women, he sees no connection between sex and love: to him, relationships are built on lies. He scoffs at the thought of he and his friends ever talking to each other about girlfriends: anyone who tried would be mocked. Love is for white people, he claims — he’s seen respect, but not affection, between his African immigrant mother and father.

Yes, there’s misogyny here, but there’s also fear and self-hatred beneath the bluster. Another speaker cites the separation between the sexes in his community as a reason for his ignorance about girls. The young men go on a road trip to Brussels and its red-light district, where prostitutes are merchandise, displayed behind windows.

There’s a sadness about the wasted potential of these lives (and anger against social conditions expressed in a rap song on the soundtrack). But, as the title suggests, there’s a movement toward warmth as the film proceeds. A gay man reveals his desire for love and closeness, and speaks with disgust about a macho code even within the gay community. He’s frustrated, but there’s hope for him. The final encounter, between a young man and woman, is a demonstration of emotional, as well as physical, intimacy. Diop captures not only the sensuousness of their bodies in contact, but also the familiarity with each other reflected in their mutual teasing. “Crack my fingers,” the girl asks the boy, and he does, dutifully. Now that’s togetherness (Towards Tenderness and We are streaming on MUBI).

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Alice Diop, Guslagie Malanda, Harvard Film Archive, saint omer, Towards Tenderness / Vers la tendress