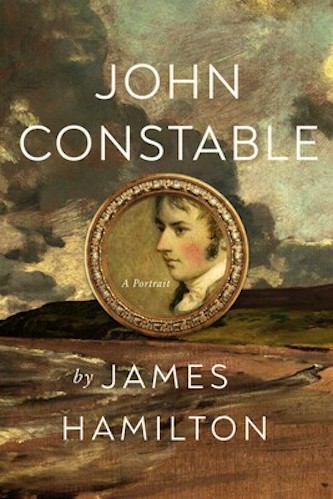

Book Review: “John Constable: A Portrait” — The Slow Triumph of a Great British Landscape Painter

By Peter Walsh

James Hamilton’s biography of British landscape painter John Constable is a highly accomplished, beautifully composed, revealing, and richly entertaining work of scholarship.

John Constable: A Portrait by James Hamilton. Pegasus Press, 496 pages, $32.

Does true genius always win out? Consider the slow triumph of the great British landscape painter John Constable. He never struggled the way Modigliani or Rothko struggled. Yet his biography suggests his life could easily have turned out otherwise: if Constable’s parents had been a little less well off or a bit less indulgent, if he had been less resilient amid the shocks and disappointments of his profession, if, as many suggested to him, he had focused his art on lucrative portraiture instead of slow-selling landscape, if he hadn’t married, after many obstacles, the love of his life, if he had been born in a city, or a little earlier than he was.

Does true genius always win out? Consider the slow triumph of the great British landscape painter John Constable. He never struggled the way Modigliani or Rothko struggled. Yet his biography suggests his life could easily have turned out otherwise: if Constable’s parents had been a little less well off or a bit less indulgent, if he had been less resilient amid the shocks and disappointments of his profession, if, as many suggested to him, he had focused his art on lucrative portraiture instead of slow-selling landscape, if he hadn’t married, after many obstacles, the love of his life, if he had been born in a city, or a little earlier than he was.

Above all, perhaps, if his friends had been less numerous, loyal, or supportive. “There is a desperation for friendship in John Constable,” writes his latest biographer, James Hamilton. “[H]e needed the assurance of recognition from solid and and reliable people who were outside his line of business, but who had the intelligence and expertise to appreciate the strains of his creativity. Artists did not do this for him. This was entirely personal to Constable: he needed a constant stream of approval.”

Constable was born in the country town of East Bergholt, Suffolk, not far north of London, seven months after Jane Austen in Hampshire and barely three weeks before the Declaration of Independence appeared in the American colonies. He died of a heart attack in 1837, less than two months before Queen Victoria ascended the throne. Thus his career encompassed the vaguely bounded “Regency Period:” the later reign of King George III and his two sons, George IV and William IV, and including the actual Regency, when George, then Prince of Wales, ruled for his incapacitated father as Prince Regent.

It was a time still much celebrated for sophisticated fashions and elegant, if sometimes riotous and ribald, living. It was also a period of great political and social change: the American Revolution separated the American colonies from England; the Act of Union politically united England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales in the United Kingdom; the Napoleonic Wars remade Europe; and the old structures of British class and power began to shift as wealth began to reshape and realign. It was a period of intense interest in science and scientific discovery. All of these helped, in subtle and less subtle ways, make the John Constable the beloved artist he is now known as — one of the two greatest British landscape painters of the 19th century.

Constable’s prosperous father, Golding, owned mills, shipping barges, a wharf and dry dock, and a substantial house in the village of East Bergholt called East Bergholt House. This meant the family was “in trade,” but they were not quite content to leave things there. A probably wishful family tree, drawn up by an archaeologist and professional genealogist, traced their lineage to Ivon, Viscount Constantine, “in Normandy.” The family prospered from mills and shipping corn to London by barge. Coal, “night soil” for fertilizer, or whatever else, could be carried back on the return route.

John Constable, the middle brother of three (there were also three sisters), was likely meant for the church, but his education ran aground on an abusive headmaster. When his older brother, also named Golding, proved temperamentally unable to take charge of the family business, John was tapped to learn the family trades in his place. But once it became clear that John meant to be a painter, the family did not throw many obstacles in his way and supported him as they could. Constable’s capable and universally loved younger brother, Abram, took over management of the family’s commercial interests. John’s formidable mother Ann, in particular, covered unpaid bills as needed and was always looking for ways to advance her talented son’s career.

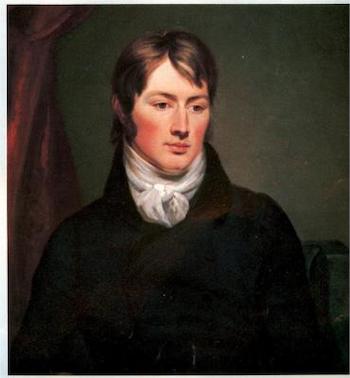

Portrait of John Constable by Ramsey Richard Reinagle.

His family’s social standing — neither gentry nor only merchant class — meant that John, as an artist, could mingle widely on either side. One of his closest friends and mentors early on was a sign painter, itinerant craftsman, and sometime artist named John Dunthorne. Dunthorne’s son, Johnnie, later became Constable’s devoted and extremely capable studio assistant in London. Through his mother, John met as a boy Rachel, Lady Beaumont, who lived in town with her second husband. Lady Beaumont’s son by her first marriage became Sir George Beaumont, 7th baronet, a wealthy, though shy, art collector who took pride in showing John his collection in London. Other useful connections were the Rt. Rev. John Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, an amateur artist, and his nephew, another John Fisher, also a clergyman and an amateur artist, who became John Constable’s lifelong close friend.

The young Constable was handsome (Bishop Fisher’s wife compared him to “one of the figures in the works of young Raphael”), presentable, and personable, at least if you weren’t a professional artist. These qualities and his obvious talent won him invitations to the country estates of wealthy collectors and art lovers, including Wilbraham, the 6th Earl of Dysart. These patrons gave him the run of their houses and collections and provided country views for him to study, including the gardens and grounds of Salisbury Cathedral, subject of some of Constable’s most celebrated works. They also gave him advice (much of it bad), and commissioned copies and family portraits. In London, a place less relaxed about class mixing, they did not always socialize.

Through these many connections that reached above his own family’s social rank, Constable met the love of his life, Maria Bicknell, granddaughter of a wealthy local clergyman and daughter of a prosperous London solicitor whose clients included the Prince Regent. Their relationship dragged on in limbo for years while her family pondered his prospects for supporting her. Once married, they produced seven children and much happiness, though the consumptive Maria wore out and died at 41. Constable, Hamilton concludes, had “loved her to death.”

Hamilton’s delightful narrative contains not just the raw materials for a fine Regency novel. There is more than enough here to fill a multivolume epic of period English life: family business, stately home visits, London adventures and city addresses, country sojourns, family confabs over dinner, professional rivalries, walks on the beach, academic competition, social comedy, intrigues over inheritances, deaths, births, battling cats, a brothel across the street, and lots of household noise. He traces the baby steps of Constable’s career as he slowly climbs the professional ladder of the Royal Academy from student to exhibitor in official exhibitions to ARA (Associate of the Royal Academy, a status Hamilton compares to being an underclassman at a traditional English boy’s school) at the age of 43. His rival Turner had been elected at 24. Year after year, Constable was put up but got no votes. The climb to RA and full membership in the Academy was almost as painful. Hamilton includes one hilarious scene in which Constable tries to lobby Turner’s vote at his home. The established but notoriously eccentric painter keeps him standing humiliated on his doorstep while barraging him with questions.

John Constable, Flatford Mill (‘Scene on a Navigable River’), 1816-17. Photo: Wiki Common

Though he was conservative in politics and religion, Constable’s painting was at the cutting edge of an artistic revolution. It was hard for many of his colleagues to see it: “very green” was the bewildered comment of some. Following long tradition, important academic painting in Britain was supposed to focus on grand dramas from history, classical mythology, or the Bible. Landscape was minor. Constable not only was a landscape painter, but his landscapes were not of the classical Roman countryside with their ruins and frolicking nymphs and satyrs. His were of familiar, homely scenes of English rural life, hardly grand enough for an aristocratic drawing room.

To compensate for this prejudice, Constable enlarged his major works to the scale of the accepted history paintings, creating “six footer” canvases that could dominate a room or stand out in a crowded exhibition gallery. His intense study of the landscapes, workaday life, light, atmosphere, and even the clouds of “Constable country,” as it was called even during his lifetime, may have been intuitive at first. But once he was well established and began giving public lectures, Constable made it clear he understood the importance of his approach. “Painting is a science,” he declared at a lecture at the Royal Institution, with the great natural scientist Michael Faraday in the audience, “and should be pursued as an inquiry into the laws of nature. Why, then, may not landscape be considered a branch of natural philosophy, of which pictures are but the experiments?”

Elsewhere, he traces the evolution of landscape from background art to center stage. “The painters of history were early made acquainted with the power and use of landscape;… and [it] so gained a dignity which has never forsaken it even when afterwards it stood alone and claimed distinction as a separate class of Art.”

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821. Photo: Wiki Common

The French recognized his great innovation, and the emphatic arrival of the Romantic period, before the British. Charles X, last Bourbon King of France, sent Constable a gold medal, presented in a ceremony at the French embassy in London by the French ambassador, Jules, Prince de Polignac, who confided that the king had been “particularly struck” by The Hay Wain, now considered one of the artist’s masterpieces. Yet, despite his aristocratic connections in England, Constable’s most important patrons tended to be from his father’s own social class: a brewer, a wine merchant, a bookseller, a paper maker, an investor and entrepreneur in men’s shirts. They represented the economic shift away from land to manufacturing and trade, and taste away from the continental snobbery of the leisure classes and toward the charms of local talent, persistence, and effort.

Hamilton uses a host of letters, diaries, and journals to weave a story that often has near-cinematic detail, in his descriptions of a busy, boisterous household and studio in London or the views from Hampstead Heath or the beach at Brighton (for the years of Constable’s marriage, the family maintained households both in the city and the country). In particular, Hamilton relies on Constable’s own writings, which he praises as “a treasure trove” for European art history, as well as his biography. Fortunately, Constable’s correspondence and journals were gathered, transcribed, indexed, and published in the ’60s in a series of handsome green volumes. “In correspondence, Constable is quicksilver.… [He] had a series of tones which he was able to slip into naturally, certainly without appearing to try.” Even if Constable’s visual works had all vanished, Hamilton claims, Constable’s “centrality as a writer” would still remain.

Hamilton also describes many of Constable’s art works in great detail, giving many more examples than are illustrated in the plates section — which, though they are in color, are usually too small to show all the critical details he refers to in his analysis. An author’s note concedes that his “book has fewer illustrations than its text desires, so I recommend that readers use the Internet to search for pictures discussed” — hardly a a convenient solution. To help with the vast number of friends, relations, neighbors, teachers, patrons, colleagues, rivals, business partners, and household servants in Constable’s life and career, Hamilton adds a four-page “Cast of Characters” in small type, in many cases with just a word or two on the entry’s profession. A few more details about the person’s connection to Constable would have made the list more useful. But these are minor flaws in what is otherwise a highly accomplished, beautifully composed, revealing, and richly entertaining work of scholarship.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Thank you for the article