Classical Concert Review: The Boston Symphony Orchestra Plays Wolfe and Górecki

By Aaron Keebaugh

Brimming with edge-of-seat intensity and fist-waving theatricality, Julia Wolfe’s oratorio Her Story is the unequivocal highlight of the current BSO season.

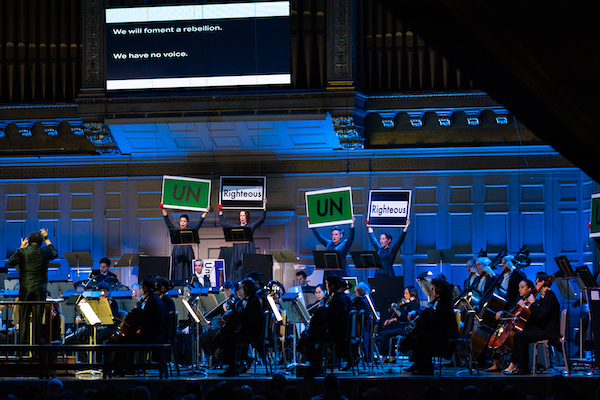

Lorelei Ensemble, conductor Giancarlo Guerrero, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing Julia Wolfe’s oratorio Her Story. Photo: Robert Torres

“I am strong,” rings out the concluding phrase of Julia Wolfe’s Her Story.

The short line encapsulates the power and immediacy of this stunning new musical and dramatic spectacle, which the Lorelei Ensemble, conductor Giancarlo Guerrero, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra perform this weekend to conclude the Voices of Loss, Reckoning, and Hope festival. Brimming with edge-of-seat intensity, Thursday’s local premiere made Her Story the unequivocal highlight of the current season.

The thirty-minute oratorio, complete with costumes and stage movement, belatedly commemorates the centennial of the 19th Amendment (The originally scheduled premiere was postponed during the pandemic). The score is all grit and fire, much like Wolfe’s other large-scale endeavors of the last decade.

Like the iconoclast Émile Zola, the composer takes a probing look at unsettling political/economic realities with no easy answers. Wolfe’s Anthracite Fields, which delves into coal-mining culture in her native Pennsylvania, won the Pulitzer Prize in 2015. Equally compelling is her Fire in My Mouth, which takes as its source the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which claimed the lives of 146 garment workers in New York in 1911. All teem with explosions of rock-like rhythms that channel palpable anger over difficult, life-altering events.

But Her Story displays volcanic fervor, ruminating on the psychological depths of the suffragette movement while simultaneously paying inspiring homage to the furious resilience of a fight for equality that still faces adversity today.

The composition revolves around a 1776 letter by Abigail Adams and the famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech by Sojourner Truth (1851). Each woman expressed strong feelings about the marginalized roles they were forced to play in a patriarchal America that continues to ignore female political agency.

Wolfe’s music literally shakes with the understandably raw and personal fury over the social barriers to the vote and progress. Textures that shimmer and scintillate frame stuttering vocal parts. Central to the score are insults that were hurled at suffragettes — everything from “unrighteous,” “Bolshevik,” and “communist,” to the common put down of “hysterical.” Percussion supplies sudden barrages of sound that feel like bold slaps in the face, as one fellow listener put it. The music surges steadily ahead before abating in the final bars.

Visually, Thursday’s performance reinforced that roiling intensity. The Lorelei Ensemble, all clad in matching grey dresses, maneuvered fluidly about the stage. At times the singers were situated behind the orchestra like a traditional choir. At others, they migrated into the orchestra itself, then to the front, all seated on a long bench. Swift hand gestures drove home the musical symbolism, with gloved hands covering the singers’ mouths as they sang of having no voice.

The Lorelei singers delivered their parts with a cold conviction that laid bare every accusatory point. Their pristine vocal blend illuminated the grand dimensions of the score’s lines, which were stacked together in towers of harmony. A baton-less Guerrero kept the orchestral forces churning in a fiery zest that, by the end, brought the audience to its feet.

Soprano Aleksandra Kurzak, conductor Giancarlo Guerrero, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra performing Górecki’s Third Symphony. Photo: Robert Torres

The first half of the concert delivered just as much gravity with Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3, Symphony of Sorrowful Songs.

The hour-long score, made popular worldwide by the 1992 London Sinfonietta recording, was a departure for the reclusive composer, who had begun his career in lockstep with the Polish post-war avant-garde. Out of his four symphonies, this one is the most compelling in its direct depiction of despair and suffering.

Polish prayers and a Silesian folk song convey the horrors and unbearable sorrow of losing a child. Chant-like phrases in the strings flow, twist, and fall away in search of solace.

In only a few fleeting moments on Thursday did the web of strings overpower Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzak, the evening’s soloist. In fact, her presence grew more focused as the music unfolded. She lofted the second movement’s text, taken from a Gestapo cell wall in Zakopane, as if it was a personal prayer. Darkly projected vocal repetitions in the finale rang like a mantra.

Guerrero’s supple direction kept everything moving forward, with the lines’ contours dictating adroit attention to subtle dynamics. But, like the grief this composition so memorably reflects, this is music that seems to slow down time. The performance served as a reminder that — for all the solace music can provide — sorrow can be intractable.

Aaron Keebaugh has been a classical music critic in Boston since 2012. His work has been featured in the Musical Times, Corymbus, Boston Classical Review, Early Music America, and BBC Radio 3. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in both Danvers and Lynn.

Tagged: Aleksandra Kurzak, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Giancarlo Guerrero, Her Story, Julia Wolfe, Lorelei Ensemble

Great review Aaron.

I’m attending tonight and am psyched for it, And kudos to The Arts Fuse for posting their review ahead of the local newspapers of note. (Actually should be newspaper.In the singular.)