March Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Hip Hop

Like many of his Backwoodz Studioz labelmates, SKECH 185 raps over beats that embrace disorientation rather than easy pleasure.

Cover art for SKECH185’s He Left Nothing for the Swim Back.

Within seconds, hip-hop artist SKECH185’s voice commands attention on his album He Left Nothing for the Swim Back. His intense flow leaves little space, allowing him to run through pages’ worth of lyrics in minutes. A former member of the Tomorrow Kids and War Church, his solo debut is entirely produced by Jeff Markey. Like many of his Backwoodz Studioz labelmates, SKECH 185 raps over beats that embrace disorientation rather than easy pleasure. Instead of simply serving as backing tracks, Markey’s music competes with the singer for attention. “The River” remains in unresolved suspension, with droning keyboards rumbling like a stalled train and scattering hi-hats. “Jay Street” samples free jazz squawks, while “Badly Drawn Hero” interpolates the Who’s “I Can See For Miles” into an anguished chorus. SKECH185 also riffs on Mobb Deep’s infinitely quoted “Shook Ones Pt. II.”

A literary impulse runs throughout the entire recording, but it’s best demonstrated on “East Side Summer.” The song turns to the subject of the singer’s youth in Chicago. While guests Jyroscope and Solar Five flesh out the song, SKECH185 describes witnessing a shooting as a 10-year-old. Without an ounce of sensationalism or bragging (“nothing cool about living through this/fuck how them songs sound!” is one of his verse’s final couplets), the track lays out the damage caused by growing up around violence: “My uncle got shot because that’s what happens to Uncles back then/Black Power devoured in the black steel in hour between street lights and mothers first scream.” The title track artfully disses Kylie Jenner’s infamous Pepsi ad. The presence of so many guests contributes to one of the album’s few sources of warmth — a communitarian feel that doesn’t detract from SKECH185’s singular voice but enhances these songs’ storytelling power. Every note and word of He Left Nothing For the Swim Back trails years of experience.

— Steve Erickson

Indie Pop

strongboi’s dreamy, shoegaze-infused snythpop recalls the experimental sounds of the Mexican Summer label and the multifarious nostalgia of chillwave.

Cover art for strongboi’s album strongboi.

Alice Phoebe Lou and Ziv Yamin are the creative minds behind strongboi, whose self-released self-titled debut album was released this month. Their dreamy, shoegaze-infused snythpop recalls the experimental sounds of the Mexican Summer label and the multifarious nostalgia of chillwave. Both currently residing in Berlin (the German government has in part financed their recordings), the two share a close friendship and a passion for eclectic music. Lou hails from South Africa and has already made a name for herself as a talented singer-songwriter, garnering attention from major labels and achieving critical acclaim while remaining true to her ethics of independent art. Yamin, on the other hand, comes from Israel and has previously performed as part of the band Hush Moss. With such diverse backgrounds and musical influences, it’s no wonder that strongboi has produced such an exciting and innovative new album.

Expectations have been high for this release since 2020, when strongboi released three singles accompanied by videos. Yet their 2023 sound comes across as less caustic, without the obvious hip-hop influence of the danceable “strongboi” and the heavy modulation of retro “honey thighs” and “tuff girl”. Contrary to the initial timbre set by the project, the lyrics and mood of this album feel much more personal, replacing pre-pandemic overt sexuality and self-promotion with vulnerability. One song, “cold”, even carries strikingly traditional R&B vibes – a lack of irony. Friend Dekel Adin (a.k.a. Daklis) assists on the tracks, and is credited with mixing one as half of the duo Haziz (whose debut album Supertiger was released last year). California producer Lindsay Olsen also contributes as Salami Rose Joe Louis on “unconditional.” It is clear that the union of these two artists can produce much more than the long-awaited 33 minutes we’ve been given here, even without the additional collaborators. But in the future fans might want to hear something a little more saucy.

Eyelids latest album is an exception only in that it might be the best of the bunch.

Cover art for A Colossal Waste of Light

Eyelids comprises members who have served in the employ of – among others – The Decemberists, Guided by Voices, Boston Spaceships, Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks, Elliott Smith, and Camper Van Beethoven.

Given that R.E.M. could occupy the center of a Venn diagram of these artists, it makes perfect sense given that Peter Buck, that band’s guitarist, has lent his producing talents to their three most recent records, including the just-released A Colossal Waste of Light (Jealous Butcher Records).

Moreover, the Portland, OR quintet’s indie rock supergroup configuration makes it completely unsurprising that all of their output is really good. Their latest offering is an exception only in that it might be the best of the bunch.

In keeping with Eyelids tradition, ACWOL is sequenced so that a composition by Chris Slusarenko (click for my 2017 interview, which includes an Eyelids family tree of sorts) is followed by one from the equally talented John Moen.

This back-and-forth showcases and reinforces each’s strengths while infusing the album with reassuring cohesion and engrossing contrast.

Slusarenko and Moen’s creative juices flow so strongly on ACWOL that there is no room for repetition or dullness to seep in. They hit their peaks, though, on tracks 8 through 11. There are potential My 10 Favorite Songs of 2023 inclusions among “The Snowfire Band,” “Everything That I See You See Better (22),” “Misuse,” and “Pink Chair.”

These four are sandwiched between the first two singles pulled from the album: Slusarenko’s hazy, engaging title track and Moen’s “Lyin’ In Your Tomb,” for which the band shot an appropriately spooky, apparently Nosferatu-inspired video.

But listeners need not wait for or skip to #7 in order to be entranced. Feasting one’s ears upon anything from the chiming, layered opener “Crawling Off Your Pages” through the pensive, minor-key midpoint “Runaway, Yeah” will suffice in that regard.

Eyelids’ March 18 visit to Atwood’s Tavern is sold-out. Here’s hoping that they return to the Boston area later in the year.

— Blake Maddux

Classical Music

Exactly 2 years ago, Lars Vogt went against his doctor’s orders and traveled to record the two extraordinary Schubert Piano Trios ( E flat, D929 and B flat, D898) with his longtime close friends and collaborators, violinist Christian Tetzlaff and his sister, cellist Tanya Tetzlaff. Their two-disc recording (Undine), made before Vogt’s death from cancer at the age of 51, came out this month and it is rapturously beautiful, even soul-stirring. This trio had already recorded trios of Dvorak and Brahms, and, with Christian and Lars, there are superb recordings of sonatas by Brahms (highly recommended), Beethoven, Schumann, and Mozart. But these recordings emanate an unearthly grandeur, its tracks including Schubert’s lovely Nocturne for String Trio and his famed Arpeggione Sonata for cello and piano.

Exactly 2 years ago, Lars Vogt went against his doctor’s orders and traveled to record the two extraordinary Schubert Piano Trios ( E flat, D929 and B flat, D898) with his longtime close friends and collaborators, violinist Christian Tetzlaff and his sister, cellist Tanya Tetzlaff. Their two-disc recording (Undine), made before Vogt’s death from cancer at the age of 51, came out this month and it is rapturously beautiful, even soul-stirring. This trio had already recorded trios of Dvorak and Brahms, and, with Christian and Lars, there are superb recordings of sonatas by Brahms (highly recommended), Beethoven, Schumann, and Mozart. But these recordings emanate an unearthly grandeur, its tracks including Schubert’s lovely Nocturne for String Trio and his famed Arpeggione Sonata for cello and piano.

One can’t help treasuring these ravishing performances as a posthumous gift from the beloved pianist, who died this past September. The liner notes, by Christian and Tanya Tetzlaff, are intimate reflections of their dear friend. In them, Christian recalls how Lars would say, “Now we’ve done it, recorded the trios. Now I could go too.” He recalls, “The recording was made shortly before his diagnosis. After each session he would lie on the sofa. He knew something catastrophic was happening… Deep inside he already knew that in all likelihood he wasn’t going to be able to live very much longer.”

The poise, vitality, energy and effervescence one hears on this CD, especially the tragic E flat Major trio, are palpable, as is the musicians’ profound love of Franz Schubert. “In Lars’s words, which I think we all share,” Christian writes, “the incredible difference between Schubert and Brahms is that Schubert shows you the absurdity, the horror and the beauty of everything, and Brahms actually takes you by your hand, and tries to give solace… With Brahms, you have somebody at your side who is very much like you, and suffering like you. Whereas you are next to Schubert, and say, ‘Who is this giant?’”

If you own only one recording of these two trios, this is the one I most heartily recommend. To give Lars Vogt the final word: “If not much time remains, then it’s a worthy farewell.”

— Susan Miron

Margaret Bonds didn’t leave behind a huge symphonic legacy but her music, much of it written in collaboration with her good friend, Langston Hughes, is as striking for its melodic naturalness as for its engagement with the Harlem Renaissance and the nascent Civil Rights Movement.

The revival of interest in music by Margaret Bonds must count as one of the most positive turns in classical music these past couple of years. The Chicago-born composer didn’t leave behind a huge symphonic legacy but her music, much of it written in collaboration with her good friend, Langston Hughes, is as striking for its melodic naturalness as for its engagement with the Harlem Renaissance and the nascent Civil Rights Movement.

The revival of interest in music by Margaret Bonds must count as one of the most positive turns in classical music these past couple of years. The Chicago-born composer didn’t leave behind a huge symphonic legacy but her music, much of it written in collaboration with her good friend, Langston Hughes, is as striking for its melodic naturalness as for its engagement with the Harlem Renaissance and the nascent Civil Rights Movement.

Both qualities emerge in this latest offering from the Dessoff Choirs & Orchestra and Malcolm J. Merriwether, which present the premiere recordings of Bonds’ Credo and Simon Bore the Cross.

The former sets W.E.B. DuBois eponymous prose poem that intertwines elements of the Christian liturgical creed with calls for racial and social justice. Bonds’ setting is typically powerful and effective, often heavily rhythmic but ever following the natural rhythm of the words. At times, as in “I Believe in the Prince of Peace,” the writing turns devotional and unaffectedly lyrical. Some moments are defiant and declamatory. Throughout, the score’s overriding impression is of emotional directness and strength.

Simon on the Cross, by contrast, offers a meditation on the events of Good Friday from the perspective of the titular character, who’s traditionally held to have been of African descent. The text, by Hughes, incorporates the Spiritual “He Never Said a Mumblin’ Word.”

Merriwether draws rousing performances from the Dessoffs, soprano Janinah Burnett, and bass-baritone Dashon Burton in both works. Credo is particularly vigorous, as comfortable in its booming, muscular statements as in the flowing, melismatic ones.

Simon, with its broad, meditative character and Spiritual allusions unfolds like a cantata. Of note is its emphasis on the Black experience being part of the defining moment of Christianity, a stance that feels timely as ever.

Not only do conductor and orchestra have this fare under their fingers: their recording of Scriabin’s Second and Fourth Symphonies holds its own with the best out there.

If one doesn’t automatically associate Buffalo, NY with performances of Alexander Scriabin’s music, one clearly hasn’t heard JoAnn Falletta’s new recording of two of the mystic Russian composer’s symphonies with the Buffalo Philharmonic. Not only do conductor and orchestra have this fare under their fingers: their recording of Scriabin’s Second and Fourth Symphonies holds its own with the best out there.

If one doesn’t automatically associate Buffalo, NY with performances of Alexander Scriabin’s music, one clearly hasn’t heard JoAnn Falletta’s new recording of two of the mystic Russian composer’s symphonies with the Buffalo Philharmonic. Not only do conductor and orchestra have this fare under their fingers: their recording of Scriabin’s Second and Fourth Symphonies holds its own with the best out there.

That’s especially true of the Philharmonic’s performance of No. 2. This 1901 score is about as sumptuous a late-Romantic effort as they come. As a result, it demands a high degree of both interpretive vision and technique. Falletta’s got both in spades.

Her feel for tempo is always right, even when things get stretched just a bit (as happens in the first movement). Yet nothing drags. The orchestra’s grasp of the music’s shifting character – by turns, airy, radiant, stormy, impassioned, majestic – is spot-on.

In the second movement, for instance, the security of the ensemble’s playing and the conductor’s understanding of how all the moving parts interact is bracing (the woodwind runs near the beginning are worth the price of the album). The third is sumptuous and beautifully balanced, while the stormy fourth flows smartly and the finale’s refrains have a stalwartly cathartic quality to them. Truly, the Buffalo brasses here are in the same league as the Chicago Symphony’s were for Neeme Järvi decades ago.

Falletta and her forces prove equally adept in Scriabin’s Symphony No. 4. Also known as The Poem of Ecstasy, this single-movement effort presents many of the same challenges as its disc-mate, though in about half the time. The present reading is clean, limber, and outstandingly transparent. Particularly compelling is the lush string writing about the Poem’s middle.

In both performances, Naxos’ engineering offers naturally resonant orchestral sound and terrific balances. Recommended.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Books

So Shall You Reap is Donna Leon’s 32nd outing with this beloved series of mysteries, which stars Commissario Buido Brunetti

Like the tides, Donna Leon’s Brunetti mysteries arrive with predictable regularity, bringing with them a bracing moral clarity cushioned by their protagonist’s cozy familial routines. And in So Shall You Reap (Grove Atlantic), the author’s 32nd outing with this beloved series, similar tidal recurrences echo throughout Venetian society, and they set the stage for a particularly cold-blooded murder of an undocumented Sri Lankan man, who has been living — with the owner’s permission — on the grounds of an academic’s palazzo. For Brunetti, whose aggressively eco-conscious daughter Chiara serves as the family’s social conscience, the most obvious echo of the past comes via her political awareness. Recalling “the rhetoric he had found so persuasive in his first years at university” — a doctrinaire socialism that didn’t take in the lived reality of people like his own working-class parents — he realizes “[h]is own children were avowing much the same ideas today.” Over the years he has come to regret his youthful rigidity; he wonders if his children will come to feel the same.

Like the tides, Donna Leon’s Brunetti mysteries arrive with predictable regularity, bringing with them a bracing moral clarity cushioned by their protagonist’s cozy familial routines. And in So Shall You Reap (Grove Atlantic), the author’s 32nd outing with this beloved series, similar tidal recurrences echo throughout Venetian society, and they set the stage for a particularly cold-blooded murder of an undocumented Sri Lankan man, who has been living — with the owner’s permission — on the grounds of an academic’s palazzo. For Brunetti, whose aggressively eco-conscious daughter Chiara serves as the family’s social conscience, the most obvious echo of the past comes via her political awareness. Recalling “the rhetoric he had found so persuasive in his first years at university” — a doctrinaire socialism that didn’t take in the lived reality of people like his own working-class parents — he realizes “[h]is own children were avowing much the same ideas today.” Over the years he has come to regret his youthful rigidity; he wonders if his children will come to feel the same.

Small wonder, then, that the dogged Commissario is intrigued when he finds political pamphlets among the belongings of Inesh Kavinda, the victim, whose makeshift home in the palazzo’s garden house is otherwise a peaceful Buddhist oasis. When those pamphlets bring up a long-abandoned cold case, he finds himself wondering if his own memories might be making connections where none exist. Luckily, his reliable colleagues in the Questura, and the intercession of a particularly joyful dog named Sara, will help him sort relevant facts from delusive memories, all in time for Brunetti to join his family for one of his wife Paola’s wonderful meals, even on the days when they all go vegan.

— Clea Simon

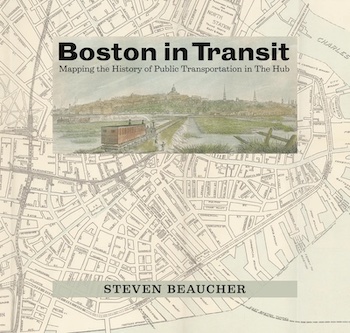

Steven Beaucher has penned a richly compelling and detailed history of the everyday experience of the Hub’s public transportation elements, experiments, and systems.

Prior to Roger Conover’s four-decade tenure (1977-2018) as Art and Architecture editor, the MIT Press published the monumental “Bauhaus” book by Hans Wingler, as well as earlier books by Walter Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Schlemmer. In other words, these volumes included seminal works by distinguished architects and architectural historians. Best-selling entries included works by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour (Learning from Las Vegas), Kevin Lynch (The Image of The City) and Charles Jencks (Adhocism).

Prior to Roger Conover’s four-decade tenure (1977-2018) as Art and Architecture editor, the MIT Press published the monumental “Bauhaus” book by Hans Wingler, as well as earlier books by Walter Gropius, Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Schlemmer. In other words, these volumes included seminal works by distinguished architects and architectural historians. Best-selling entries included works by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour (Learning from Las Vegas), Kevin Lynch (The Image of The City) and Charles Jencks (Adhocism).

When Conover retired, his legacy was far less impressive. Besides releasing the expected professorial manifestos and star architect monographs, the editor’s last couple of decades seemed to be devoted to publishing books that — when they are not the result of networking friends of friends — were either esoteric dissertations or quirky, if not silly, tangentially related architecture and urban design books. Examples of the latter include Eating Architecture (the relationship between food and architecture), The Springboard and the Pond (the intimate History of the swimming pool), Architects’ Gravesites (no explanation necessary). Who bought these tomes?

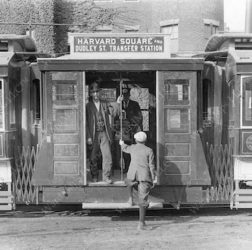

He was replaced in 2019 by Thomas Weaver. Unlike Conover, Weaver has extensive prior experience in the world of architecture. So, it is refreshing (and reassuring) to report that MIT Press is putting out a major urban transportation conpendium, a remarkably illustrated coffee table book about the centuries old evolution of public transit in and around Boston. Beginning in 1630, Steven Beaucher’s Boston in Transit: Mapping the History of Public Transportation in The Hub chronicles the complete history of the various modes of transportation that have kept Beantown moving and expanding. Starting with a single ferry between Charlestown and the North End, the narrative vividly describes how transportation became an intrinsic part of Boston’s physical character and personality. Here horse-drawn coaches begat Omnibus and horse-pulled trams begat electric trolleys and trains that helped the suburbs to flower.

1912 MBTA ‘Snake’ Train

Utilizing wonderful photographs, engineering drawings, brochures, guidebooks, timetables, and even tickets from his own extensive collection of Boston transit ephemera, Beaucher has created a richly compelling and detailed history of the everyday experience of the Hub’s public transportation elements, experiments, and systems.

When my paternal grandmother first arrived in Boston in 1904, family legend tells that she wrote a letter to her brothers in rural Latvia. She told them, “Today I went into Hell.” Apparently, she had visited the subway. Some things just don’t change.

–Mark Favermann

Arch-Conspirator is a respectful — I am tempted to say affectionate — homage/update to Sophocles.

I remain a staunch Hegelian when it comes to Sophocles’ masterpiece, Antigone. The German philosopher’s interpretation is my bedrock: this is not a tragedy about right versus wrong, but an even-handed battle between two ‘rights’ – Kreon’s violent rage for civic order is pitted against Antigone’s psychotic obsession with obeying the desire of the gods. Both sides are insanely self-involved – the good of the community stands well outside of this extreme battle of wills, which is only incidentally about the corruption of the present and the despoliation of tradition.

This doesn’t mean I don’t readily appreciate other incisive interpretations, which are bountiful, such as Jean Anouilh’s powerful 1944 version, which tapped into the French Resistance and the Nazi occupation. And, of course, Antigone has become a feminist icon (of sorts), her death an act of martyrdom against the brutalizing patriarchy. That is where best-selling writer Veronica Roth’s sci-fi version, Arch-Conspirator (Tor Books), sits, its stream-lined dystopian vision drawing on elements of The Handmaid’s Tale.

Thebes is surrounded by a nuked no-man’s-land and radiation poisoning has damaged the population’s genetic material: extractions of blood and tissue from the dead (called ichor) are placed in a public display (the Archive), stored for what might be (for the faithful) an eventual “resurrection.” Women are forced into childbirth with pre-selected mates. Antigone’s father (the city’s last democratic ruler) and mother (a brilliant scientist) have been murdered, their children taken in by Uncle Kreon, who rules the city with authoritarian guile. In this telling, Polyneikes is a revolutionary leader killed during an attempted coup. Antigone does not believe in the gods, but seeks revenge on the unyielding tyrant by obeying her beloved brother’s final wish — to have his ichor extracted, which Kreon has expressly forbidden. And there is the obligatory rocket ship.

The chapters in this novella are narrated by different characters. Along with Antigone there’s Kreon’s complicit wife, Eurydice, Antigone’s sister, Ismene (here supplied with more backbone than usual), and Haemon, Antigone’s intended, who is portrayed as an empathetic (i.e. not all men are bad) strong but silent type. Roth opens up the dramatic action to bring in other figures, including glimpses of the rebel underground. The author’s sympathies — unlike Sophocles’ — are obvious. We are not given a chapter in which Kreon mourns the death of his son, though he does in the play. The emphasis is on propelling the plot, not depth of characterization. Eurydice, with her divided loyalties, is easily the most complex figure in this interpretation. Most of the suspense is generated by our wondering how Antigone’s fate is going to be handled. What kind of doom are we going to be served? Inspiring? Nihilistic? I see it as a tragic spin on feminist solidarity. Arch-Conspirator is a respectful — I am tempted to say affectionate — homage/update to Sophocles. The book will have done valuable service if it brings readers back to the original and its various adaptations. As Roth aptly proclaims in her acknowledgements: “Hot damn, what a play.”

— Bill Marx

TikTok

By satirizing (intentionally?) terrible cooking videos, Tanara “Double Chocolate” Mallory underlines their utter banality.

TikTok may very well be the pinnacle of the social media revolution. It has encouraged unprecedented levels of anarchy in short-form content, complacency in social engineering, and vulnerability in international cybersecurity. If there is an upside to all this mischief, it’d have to be Tanara “Double Chocolate” Mallory. Her videos invite us to reflect, with raucous amusement, on the poor quality of the work that Tik Tock disseminates and we are consuming, The Philadelphian began on that platform in 2019, eventually discovering a wildly successful formula of patronizingly narrating bad cooking videos. Since then she has garnered millions of followers who adore such sarcastic catch phrases as “It ain’t gone slide down easy if it ain’t cheesy” and “Everybody’s so creative!” She’s even been featured in PhillyVoice and on local television.

TikTok may very well be the pinnacle of the social media revolution. It has encouraged unprecedented levels of anarchy in short-form content, complacency in social engineering, and vulnerability in international cybersecurity. If there is an upside to all this mischief, it’d have to be Tanara “Double Chocolate” Mallory. Her videos invite us to reflect, with raucous amusement, on the poor quality of the work that Tik Tock disseminates and we are consuming, The Philadelphian began on that platform in 2019, eventually discovering a wildly successful formula of patronizingly narrating bad cooking videos. Since then she has garnered millions of followers who adore such sarcastic catch phrases as “It ain’t gone slide down easy if it ain’t cheesy” and “Everybody’s so creative!” She’s even been featured in PhillyVoice and on local television.

Attention of all kinds has become legal tender in today’s data-mining social media industry. That includes anger. The same economics that brought us thirst traps and the schadenfreude of masochistic mukbangs also reward content creators for trolling viewers with absurd, incorrect, or inflammatory content through painstakingly curated “rage view” accounts. Mallory expertly mocks these bottom feeders of the TikTok/Reels format. By satirizing (intentionally?) terrible cooking videos, she underlines their utter banality. She inspires us to reconsider the value of following yuppies as they carefully make under-/overcooked, excessively-cheesy, subpar prison spreads in luxury kitchens. Mallory’s commentary eggs on the gourmet insanity with false encouragement and outbursts of anger. By articulating our rage, she helps break the infernal spell.

And that spell is the siren call of manipulation by those who have the abundant resources to pull it off. This is the age of “if you’re not paying, you are the product.” Mallory points out our gullibility when she declares that “Everybody’s so creative!” We all know that the myths of social media meritocracy and democratization are false. The irony is that those who are supposedly dedicated to making us believe in our own capacities are often the least talented, and most ill-intentioned. But boy, do they ever waste our time.

Film

As hard as it is to watch at times, Stolen Youth is a compelling exploration of the damage wrought by narcissistic predators and the failure to recognize their behavior before it’s too late.

A scene from Hulu’s Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult at Sarah Lawrence.

When a shocking article exploring a strange cult-like situation at Sarah Lawrence College was published in New York Magazine in 2019, officials were persuaded to begin investigating the criminal nature of the accusations. A campus dorm was the setting: a student whose father (Larry Ray) had just been released from prison for securities fraud invited him to come live in her dorm because he had “nowhere to go.” The liberal-minded roommates were okay with it, and when the dad started cooking dinner and offering dad-like advice, they came to appreciate having him around. Then it got weird; well, weirder than just having a middle-aged man sleeping on your dorm couch. Ray started using mind-control tactics to convince the students they weren’t reaching their full potential. He forced them into a grueling physical fitness regime and spent hours grilling them about their efforts to improve themselves. He later convinced them they were being poisoned, and after some of them moved in with him in a New York apartment he commandeered from a friend, he insisted they owed him money for items they “damaged.” Eventually, Ray forced two of the young women into prostitution.

The new Hulu documentary miniseries Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult at Sarah Lawrence packs a lot of disturbing and revealing information into three episodes. One of the most astounding aspects the presentation is that most of the damning footage was recorded via cell phone video by Larry Ray, who apparently believed he needed a record of this important “work.” Here’s the thing though: we often think of narcissists as being very calculating and clever. But, listening to Larry berate and manipulate these students, I didn’t find him to be terribly intelligent or charismatic. And yet, these young people were controlled and traumatized by him for years. Last month, two weeks before the premiere of the series, Ray was sentenced to 60 years in prison for sex trafficking and extortion. As hard as it is to watch at times, Stolen Youth is a compelling exploration of the damage wrought by narcissistic predators and the failure to recognize their behavior before it’s too late.

This Irish-Filipino co-production is not as conceptually strong as Lorcan Finnegan and Garret Shanley’s debut effort, but it continues to develop their commitment to invigorating the horror genre with provocative themes.

A scene from Nocebo.

From Vivarium director Lorcan Finnegan and screenwriter Garret Shanley comes Nocebo, a horror thriller tinged with magic realism and folklore. The magnificent Eva Green stars as Christine, a successful fashion designer who runs her business with focus and energy. She suddenly becomes ill with a mysterious ailment that baffles her doctors. She claims to have pain, skin rashes, insomnia, and headaches, but no medical cause can be determined. Her husband Felix (1917’s Mark Strong) begins to lose patience as he watches his once capable wife become increasingly helpless. Hints arrive of a traumatic event that occurred in one of Christine’s work sites in the Philippines, suggesting that her illness may be psychological, perhaps stress-induced. A stranger shows up at Christine’s door one day: it is Diana (Chai Fonacier) and she offers to help the ill woman with all her problems. Trapped in her brain-fog, a relieved Christine accepts Diana’s assistance: she assumes a role that is part healer and part housekeeper. The woman cleans and cooks meals: Felix and daughter Roberta (Billie Gadson) are befuddled by Diana — where did she come from? — but they are grateful to have the household’s stability restored. Meanwhile, Diana begins to perform healing rituals with Christine, designed to help the afflicted woman remember events that are at the root of her illness.

Many of the metaphorical threads here are intriguing. There’s the global paranoia surrounding health that the pandemic has unleashed; Christine’s vague symptoms echo fears surrounding Long COVID. The issue of privilege is raised by her refusal to acknowledge her part in a tragedy that impacted the lives of her Filipino employees. Using folkloric healing, Diana forces Christine to confront her Eurocentric and exploitative business practices, as well as her unresolved guilt. In terms of narrative, there are problematic issues of continuity and context. Diana is an enigma: Is she an actual person? Or a nightmare-inducing specter? That ambiguity is used effectively: the film’s atmosphere generates some creepy suspense and horror. The cast is excellent, transcending the script’s occasional lack of clarity. This Irish-Filipino co-production is not as conceptually strong as Finnegan and Shanley’s debut effort, Vivarium, but it continues to develop their commitment to invigorating the horror genre with provocative themes. (Nocebo is streaming on Prime and AppleTV, and other channels)

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: Alice Phoebe Lou, Antigone, Arch-Conspirator, Backwoodz Studioz, Blake Maddux, Boston in Transit: Mapping the History of Public Transportation in The Hub, Buffalo Philharmonic, Christian Tezlaff, Clea Simon, Donna Leon, Eyelids, Garret Shanley, Greek Tragedy, Grove Atlantic, JoAnn Falletta, Lars Vogt, Lorcan Finnegan, Margaret Bonds, Mark Favermann, MIT Press, Nocebo, Ondine, science-fiction, SKECH185, So Shall You Reap, Sophocles, Steve Erickson, Steven Beaucher, Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult at Sarah Lawrence, strongboi, Tanya Tetzlaff, Veronica Roth