February Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

A welcome and brilliantly played reminder of the potential joys of wandering off beaten musical paths.

Though the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra is generally held to be among the more conservative musical institutions out there, the ensemble’s demonstrated a certain willingness to explore unperformed corners of the repertoire when it comes to their annual New Year’s Concerts. After devoting roughly a third of their last several Concerts’ programs to previously unplayed music by the Strausses and their contemporaries, they took the plunge in 2023: more than three-quarters of this year’s Concert is new to the orchestra – as well as, presumably, much of its audience.

Though the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra is generally held to be among the more conservative musical institutions out there, the ensemble’s demonstrated a certain willingness to explore unperformed corners of the repertoire when it comes to their annual New Year’s Concerts. After devoting roughly a third of their last several Concerts’ programs to previously unplayed music by the Strausses and their contemporaries, they took the plunge in 2023: more than three-quarters of this year’s Concert is new to the orchestra – as well as, presumably, much of its audience.

One certainly doesn’t suspect that, given the robust, idiomatic performances from the Philharmonic and conductor Franz Welser-Möst. Indeed, their vigor and advocacy is commendable.

The album’s biggest winner is Josef Strauss. The middle of the three Strauss brothers, he’s generally regarded as the finest composer of the trio – a distinction that’s largely upheld by the selections on offer here. Of the six waltzes on this program, four are Josef’s: Heldengedichte, Perlen der Liebe, Zeisserln, and Aquarellen. All evince a wonderful balance between lyricism and melancholy that’s a hallmark of this genre.

Among other highlights are Carl Michael Ziehrer’s In lauschiger Nacht and Franz von Suppé’s Isabella Overture. Eduard Strauss, who probably warrants the same attention his brother gets this year in some upcoming Concert, is represented by a pair of fast dances, Wer tanzt mit? and Auf und Davon.

That the recording (for Sony Classical) succeeds so well without relying heavily on music by Johann, Jr. is notable. He’s here, alright, but sparingly. One wonders if and how Christian Thielemann, who led an exceptional Neujahrskonzert in 2019, will build on Welser-Möst’s model next January. Until then, this is a welcome and brilliantly played reminder of the potential joys of wandering off beaten musical paths.

All of the music is played with a terrific sense of style and occasion by Les Siécles.

Though it may sometimes appear otherwise, the Viennese haven’t got a monopoly on the 19th century’s most enchanting dances and overtures. That realization is part of the charm of Les Nuits de Paris, the latest release from the ever-versatile and surprising Les Siécles and conductor François-Xavier Roth.

Some of its seventeen selections are familiar: music from Gounod’s Faust and Delibes’ Coppelia, Waldteufel’s Les Patineurs, and Ambroise Thomas’s Overture to Raymond among them. But most of these pieces are discoveries.

They include Camille Saint-Saëns’ graceful waltz Le Timbre d’argent and a delightfully droll one by Hervé called “Sports in England.” Waldteufel, who usually comes off as something of a one-hit-wonder, makes a stronger case for himself with the Grande Vitesse Galop and Bella Bocca Polka. Isaac Strauss (no relation to the Viennese dynasty), is likewise well represented with the jaunty Hébé-Polka and a quadrille on themes from Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld.

All of the music is played with a terrific sense of style and occasion by Les Siécles. Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that one of the most flexible orchestras on the scene should take so naturally to this fare: after all, they deliver everything from Méhul to Stravinsky and with perfect clarity and command. Still, the performances impress for their spirit, the period wind and brass instruments providing these numbers just the right degree of bite.

In some respects, in fact, the whole album (for Bru Zane) pairs wonderfully with the Nikolaus Harnoncourt/Concentus Musicus Wien 2012 release, Walzer Revolution. That one, in addition to giving us essential performances of Josef Lanner, shined a welcome light on the early years of the eponymous Viennese tradition. Here, Roth and Les Siécles do the same thing for a slice of late-19th-century Parisian musical culture. It’s a blast.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Jazz

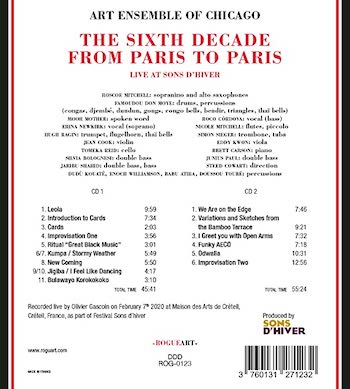

The Art Ensemble of Chicago is an enduring musical institution that, as the title of the group’s latest release indicates, has been around for more than half a century, wowing live audiences and producing dozens of albums along the way.

The Sixth Decade from Paris to Paris: Live at Sons D’River is a two-disc set recorded live at a festival in France in early 2020. Original Ensemble members Roscoe Mitchell (sopranino and alto saxophones) and Famoudou Don Moye (drums and various percussion) lead an expanded assemblage of top players from the edgier realms of jazz. Names that first jumped out at me from the album cover were Nicole Mitchell (flutes, piccolo), Tomeka Reid (cello), Jaribu Shahid (bass), Moor Mother (spoken word), and Hugh Ragin (trumpet, flugelhorn, Thai bells). But all involved, and there are many more, are exemplary.

Despite the large number of musicians, the music feels relaxed and natural despite its occasional complexity, encouraging one to sit back and take it all in.

Disc one seems to be launching out into the nether world, embracing, with powerful orchestral portent, a spacious drama triggered by Moor Mother’s recitation, which centers on rejoicing in “a higher place.” A bit later, “Ritual ‘Great Black Music’” sets the percussive stage for a spirited “Kumpa/Stormy Weather,” led by Don Moye’s djembé, and then onto “New Coming”‘s celebratory pathway.

The longer second disc starts out chamber-ish, with the strings bobbing and weaving through “We Are on the Edge” and “Variations and Sketches from the Bamboo Terrace.” Ragin hurls out a few choice lines but the real fun comes by way of an extended solo from pianist Brett Carson. Pointillism tackles the void as Carson unspools the kind of solo that suggests a center rather than establishing one. This an impressive highlight from a player worth seeking out.

“Funky AECO” feeds the urge to move, while “Odwalla,” the perennial Art Ensemble vamp, provides a chance for player introductions. Darned if the tune doesn’t still mesmerize.

Finally, “Improvisation Two” begins with spooky vocals from Roco Córdova and Erina Newkirk. Something is summoned and then lamented as mournful low strings buoy a spoken word trip through a dangerous place where “They got ‘em real good” and onto a hand-clapping march down the boulevard.

— Steve Feeney

Visual Art

This monumental piece is not as terrible as its critics insist nor as wonderful as its fans proclaim.

The Embrace by Hank Willis Thomas on the Boston Common. Photo: Mass Design Group.

Now open to the public, last month the 22-foot tall The Embrace memorial was formally unveiled on Boston Common. Set near the Parkman Bandstand, the statue is the first new permanent monument on the Boston Common in more than 30 years. However, as with much public art, there is inevitably controversy.

Created by conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas and privately funded, The Embrace abstractly memorializes the hug Dr. King shared with his wife Coretta after he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Dedicated to racial equality, this sculpture is particularly provocative given that it is prominently showcased at America’s oldest public park, the Boston Common. Still, the artist’s abstraction has become others’ distraction.

The creative process began six years ago with a national call for proposals. There were 126 submissions and five finalists chosen. Ballots sent in by Boston citizens deemed Thomas’ concept the favorite.

The artist designed the memorial to allow visitors to walk through The Embrace and personally experience the spirituality of the hug. Fans of the public artwork argue that it underscores notions of the universality of humanity, not just the ideal of social justice espoused by these two Civil Rights icons. Naysayers insist that it is unworthy of Martin and Coretta King, even insulting to their memory. Some even call the image phallic.

Right wing media, such as New York Post, UK’s Daily Mail, The Boston Herald, and many of their ideological followers have had a field day hammering the piece as an example of “woke” art, an expensive — and sanitized — homage to a flawed leader. That said, even articles in The Washington Post have been critical of the sculpture, describing it as a headless and faceless metaphor for minority status. The Embrace is a celebration to some, a graceless failure to others. As an example of public art that’s intended to be provocative, the sculpture certainly has a presence. This monumental piece is not as terrible as its critics insist nor as wonderful as its fans proclaim.

Poised on a patterned concrete pad and semi-circled by a graceful seating configuration designed by architectural project partner Mass Design Group, this selectively representational form is an idiosyncratic visual expression in a dark bronze patina. Is The Embrace a controversial focal point in the Boston Common? A permanent symbol of hope for our city and nation? Or a racial justice scab that society will feel free to pick at? Take your pick. The bottom line: The Embrace is a work of public art that is generating debate and even controversy. Isn’t that what successful art is supposed to do?

— Mark Favermann

Film

Alice Diop’s performance is profoundly moving: she conveys the slow unraveling of a woman caught in an exploitative situation that, to all outward appearances, looks respectable and safe.

Anna Diop plays a Senegalese caretaker in a scene from Nanny.

A fine feature debut from filmmaker Nikyatu Jusu, Nanny is the story of a young African immigrant mother who works as a nanny for a wealthy white Manhattan couple. Aisha (Anna Diop) is a kind and hardworking caregiver, and the children she is in charge of adore her. But she desperately misses her own child back home, and often questions her decision to remain apart from him, even though she is working to make a better life for them both. Phone calls and video messages are a poor substitute for loving contact.

Meanwhile, the couple she works for (True Detective’s Michelle Monaghan and The Gilded Age’s Morgan Spector) are pleasant enough but they engage in subtle forms of inappropriate behavior, eventually compromising Aisha’s ability to keep working for them. Stressed and lonely, Aisha connects with a warm-hearted man (Sinqua Walls) who reaffirms her beleaguered sense of self. Still, her job continues to drain her emotionally. The film has a dreamy visual quality that underscores the subtle terror of Aisha’s existence, helped along by the inventive cinematography of Rina Yang (who has also worked on HBO’s Euphoria). Dreams and nightmares full of visions of water are both calming and unsettling; they symbolize conflicting dimensions of Aisha’s predicament. Diop’s performance is profoundly moving: she conveys the slow unraveling of a woman caught in an exploitative situation that, to all outward appearances, looks respectable and safe. (Available on Amazon Prime)

This riveting tale of survival is unlike any film I’ve seen in recent memory: naturalistic in its story and performances, but also infused with a sense of magic and mysticism.

A scene from The Kings of the World.

The Columbian film (and official Oscar entry from Columbia for 2023) The Kings of the World is the third feature by filmmaker Laura Mora Ortega. Five friends, all teenage boys, live a rough life on the streets of Medellin. One of them has applied to be granted ownership of a piece of ancestral land. After many months of dealing with bureaucratic red tape, he is finally given the ownership papers. With his four friends, he sets out to travel across Columbia to lay his claim and start a new life.

The property, set in a beautiful hilly valley, represents a vision of freedom and home to the boys whose lives of loss and poverty have toughened them and left them little hope for the future. Their excitement in traveling to their new home is offset by many trials along the way: bad weather, thieves who steal their meager belongings, and a general sense of failure. But they also find kindness and support: at a brothel full of middle-aged women, where they are fed and nurtured, and from an elderly man who lives alone in a modest hut in the middle of nowhere. Tragedy besets them, also, and not all of the boys reach their destination. This riveting tale of survival is unlike any film I’ve seen in recent memory: naturalistic in its story and performances, but also infused with a sense of magic and mysticism. The young actors at its heart express a wide-range of emotions: savvy and streetwise, beaten down by misfortune, they end up embracing a jubilant sense of hope and awe in the presence of wild nature. (Available on Netflix)

To Lesile’s performances are much stronger than the film’s somewhat predictable story line.

Andrea Riseborough in a scene from To Leslie.

To Leslie is an indie film that attracted a lot of attention recently due to a viral social media campaign to nab an Oscar nomination for lead actress Andrea Riseborough (Nancy, Possessor), whose career has been characterized by a diverse array of unusual roles. Riseborough, who is English, is indeed very impressive as Leslie, a woman from West Texas who returns to her home after a long absence to face her troubled past.

The film opens with video footage of Leslie winning nearly $200,000 in the lottery. Six years later, she is being thrown out of a hotel with her belongings. Pale, exhausted, and looking like she’s neglected her hygiene for weeks, Leslie makes a phone call and winds up meeting her estranged young son (a terrific Owen Teague) at a bus station and staying with him briefly. We learn she has alienated most of her friends and family with her manipulative and self-destructive behavior, exacerbated by her alcohol addiction. After abusing her son’s hospitality, she winds up hanging around an old motel in the desert. Run by a ragtag pair of caretakers, Sweeney (Marc Maron) and Royal (Andre Royo), Leslie is generously offered a chance to work as a cleaner in exchange for room and board. She screws up more than once, and is also bullied by a pack of extended family members (led by Allison Janney). But somehow Leslie manages to turn it around. For me, the film’s performances are much stronger than the somewhat predictable storyline (script by Ryan Binaco). Director Michael Morris (who has worked on Better Call Saul and Bloodline) does a fine job with this story of working class struggle played out by an assortment of intriguing characters. (Available on Amazon Prime and AppleTV)

— Peg Aloi

A Little Prayer leaves much unresolved: it chronicles the sad, small battles that good families everywhere struggle with everyday.

David Strathairn and Celia Weston in a scene from A Little Prayer.

A Little Prayer, for which Sony Pictures has acquired the worldwide rights, is a family drama written and directed by Angus MacLachlan (Junebug). He sets the film in his home turf of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. MacLachlan, who is also a playwright and was once a fledgling actor, uses smart casting and sharp dialogue to undercut the story’s potential for melodrama. The conflicts are kept realistic and problems are not always resolved the way characters would hope. Traumas hold on tenaciously, as they do in real life.

David Strathairn is Bill and Celia Weston plays his wife, Venida. Wes Pullen is their son, David, who works at Bill’s sheet metal business. David lives at the family’s home with his wife Tammy, played by Jane Levy, who gives a heartbreaking performance. It is suggested that Tammy had a less than ideal upbringing; Bill has become, in essence, a surrogate father. Meanwhile, Bill and Venida’s daughter arrives with her own young daughter to escape life with her husband, who we learn is an addict. Meanwhile, Bill suspects that his son David may be having an affair with a woman from the office at work. As revelations mount and pressures add up, Bill tries to gently intervene on behalf of his daughter-in-law. But, as in life, the best of intentions do not always lead to satisfying solutions.

The family’s conflicts unfold via a series of quiet but revelatory scenes. The role of a father under emotional strain is quintessential Strathairn, and he fills Bill with kindness as well as beleaguered intelligence. As Bill’s wife, Weston (who was also in Junebug) subtly modulates her role with patience and humor. To its critic, A Little Prayer leaves much unresolved: it chronicles the sad, small battles that good families everywhere struggle with everyday.

Given that so much art is currently being produced by people of color in theater, the visual arts, literature, and film, hers is the kind of mentoring voice we need to hear.

Poet Nikki Giovanni in a scene from Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project.

Poet Nikki Giovanni gets a long deserved documentary on her life and work in Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project. The title comes from a line of her poetry: “The trip to Mars can only be understood through Black Americans.” The idea of transport, reinvention, and empowerment alluded to in that stanza echoes throughout her work. This impressionistic film flips back and forth in time and draws on recent interviews with Black artists as well as considerable archival footage. Giovanni writes and speaks eloquently on history, family, independence, and Black liberation, always with a glowing smile. She is not a woman to suffer fools, or compromise. In her 20s, she was deeply involved with the Black Arts Black Power movement of the ’60s. In an interview from 1971, when she was 28, we see her hold her own in conversation with 48 year-old James Baldwin. In 1970, 1971, and 1972 she received Women of the Year Awards. Now 79 (though she was a few years younger when interviewed for the film), she has earned a long list of accolades and awards.

Producer-directors Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson employed a large production crew who worked through the pandemic to weave together images that play evocatively with Giovanni’s poetry, which assembles gentle ironies before arriving at its larger point. The poet’s honesty about gender, her aging body, and the travails of family are strikingly honest. Given that so much art is currently being produced by people of color in theater, the visual arts, literature and film, this is the kind of mentoring voice we need to hear. Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project received the Sundance Documentary Grand Jury Prize.

— Tim Jackson

Books

Jews, Food, and Spain is by no means an easy read, but it is a treasure chest of Jewish history and culture, a cornucopia of unusually surprising discoveries.

“To eat is to remember” is the guiding philosophy behind Sephardic food historian Hélène Jawhara Piñer’s latest book, subtitled The Oldest Medieval Spanish Cookbook and the Sephardic Culinary Heritage (Academic Studies Press). Initially, this is hard-going reading: the volume is so thoroughly researched that the details become overwhelming (it began life as her doctoral dissertation in Medieval History and the History of Food).

“To eat is to remember” is the guiding philosophy behind Sephardic food historian Hélène Jawhara Piñer’s latest book, subtitled The Oldest Medieval Spanish Cookbook and the Sephardic Culinary Heritage (Academic Studies Press). Initially, this is hard-going reading: the volume is so thoroughly researched that the details become overwhelming (it began life as her doctoral dissertation in Medieval History and the History of Food).

But be patient: Jews, Food, and Spain is a treasure chest of Jewish history and culture, a cornucopia of unusually surprising discoveries. There are arresting facts on every page.

My previous experience with Jawhara Piñer was her luscious Sephardi: Cooking the History, Recipes of the Jews of Spain and the Diaspora, From the 13th Century to Today, a glamorous cookbook filled with stories about ingredients and recipes used in medieval Spain and the Sephardic diaspora. (She excludes tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, chilies, and any other “new world” ingredient that were not present in the Iberian Peninsula before the 16th century.) Included are recipes for caçulelas, or eggplants with saffron and Swiss chard, converso fish pie, calentita, a savory chickpea flour cake from Gibraltar, and a 13th-century Iberian rice pudding. This is a compelling, if at times morbid, (much of Jawhara Piñer’s research draws from testimony gleaned by the Inquisition) exploration of food culture that also ruminated, in unexpected ways, on Jewish cultural heritage.

The infamous 1492 Alhambra Decree forced Jews to either leave Spain or convert. Jawhara Piñer argues that food was used by hostile non-Jews as a weapon, a means to identify — and then to denounce, mock, and judge — their Jewish neighbors. Jews, Food, and Spain focuses on three centuries, the 13th to 16th, a period when cookbooks along with evidence from various Inquisition trials provides information about the food preferences and culinary practices of Iberian Jews.

The volume’s explorations of how pork, eggplant, cilantro, and adafiina (a Sabbath dish that is cooked “buried” under a hot stone) contributed to Jewish cooking are revelatory. Small but powerful insights are also supplied about the precariousness of Jewish existence at the time: for example, the women who were accused in the Inquisition were often betrayed by other women servants or neighbors. Historically, the Jews were known as People of the Book. But Jawhara Piñer argues that their social identity was intimately connected to their culinary practices, reinforced by the Sabbath and holidays. “Historical, adaptable, transmittable, territorial, diasporic, and nostalgic best defines the cuisine of Jews and Sephardim,” Jews, Food, and Spain concludes. The rest is commentary, and the book serves up a smorgasbord of that.

— Susan Miron

Decent People is a fine but sad book that tackles tough questions about racism and homophobia.

In the little town of West Mills, North Carolina a triple homicide leaves the townspeople upset and wondering why. De’Shawn Charles Winslow’s latest book, Decent People (Bloomsbury) revolves around the crime, and it takes the reader into a hypnotic, and politically-tinged, tale of deception and murder.

In the little town of West Mills, North Carolina a triple homicide leaves the townspeople upset and wondering why. De’Shawn Charles Winslow’s latest book, Decent People (Bloomsbury) revolves around the crime, and it takes the reader into a hypnotic, and politically-tinged, tale of deception and murder.

The area’s law officers refuse to do a thorough investigation because the deceased are Black. Josephine Wright, recently returned to her hometown from up north, is forced into doing some sleuthing. She has little choice: her fiance. Olympus “Lymp” Seymore has been accused of murdering his three siblings. So Jo, as she is referred to, proceeds to ask some suspicious people some very personal questions. Eunice Loving and Savannah Russett, two women who recently had an altercation with Dr. Marion Harmon, one of the deceased, are prime suspects in Jo’s mind. Winslow dedicates several chapters to this pair, probing their lives and backgrounds.

The book’s main characters live on the west side of the canal, a color line that separates Blacks from whites. Savannah Russet, a white woman from the east side of town, crossed the canal and ended up marrying a Black man. Because of the town’s racism, Savannah and Fitz leave and settle in New York City. She returns to her hometown after Fitz unexpectedly dies. She is greeted by most in West Mills, with indifference. Her one friend, Marva Harmon, was one of the three who were gunned down.

Eunice Loving became involved with the Harmons when she sent her son, La’roy, to Dr. Harmon for problematic treatment. La’Roy Loving was a very feminine acting boy and Eunice wanted Dr.Harmon to straighten him out, so to speak. Conversion therapy circa 1976 was as primitive as you might imagine. When she finds out what really happened to her son La’Roy. Eunice becomes enraged.

Winslow treats his small town characters, for all their faults and traumas, with enormous sympathy. Jo’s interrogations of witnesses are skillfully done and the narrative keeps the reader guessing through misdirection, sometimes via the speculations of West Mills’ citizens.

Even though there is only one scene in the Shiloh Missionary Baptist church in West Mills, religion plays an integral part in the overall drama. The decent people of West Mills go to that church and believe that the God of the Bible condemns homosexuality. Herschel, Jo’s brother, lives a quiet life with his male partner in far away New York City. What drove his expulsion from West Mills isn’t revealed until the end of the book. There are flickers of humor here, and Josephine Wright’s empathy for others never wavers, but Decent People is a fine but sad book that tackles tough questions about racism and homophobia.

— Brooks Geiken

World Music

Celebrated Tunisian jazz musician Dhafer Youssef has been a musical explorer for decades and he continues on his journey with his tenth studio album, Street Of Minarets. A singer and oud player, he uses his pear-shaped, lute-like North African and Near Eastern instrument in unconventional ways. The son of a muezzin, his throaty vocals weave in and out of his songs like a keening desert wind.

Celebrated Tunisian jazz musician Dhafer Youssef has been a musical explorer for decades and he continues on his journey with his tenth studio album, Street Of Minarets. A singer and oud player, he uses his pear-shaped, lute-like North African and Near Eastern instrument in unconventional ways. The son of a muezzin, his throaty vocals weave in and out of his songs like a keening desert wind.

Youssef is a devotee of Sufi poets, and there is a three-part suite here, “Flying Dervish,” dedicated to Omar Khayyam, the Persian polymath and poet revered by many Sufis. But this is far from traditional North African music and Qawwali, given that the instrumental lineup includes Herbie Hancock on piano and other guests, such as Marcus Miller (bass), Nguyên Lê (guitar), Rakesh Chaurasia (flute), Adriano Dos Santos Tenori (percussion), Dave Holland (double bass), Vinnie Colaiuta (drums), and Ambrose Akinmusire (trumpet). There’s plenty of jazz, along with a funky retro ’70s groove that alternates with delicately plucked oud melodies. The track “Whirling In The Air” is particularly lovely. Youssef’s oud evokes a Dervish dance while Chaurasia’s flute suggests the sky above and Miller’s bass the earth below.

“Ondes Of Chakras,” the closing track, is the single that’s been released for radio play. Lê’s guitar intro owes something to the desert blues of the American Southwest: it’s all instrumental and all very dreamy. Youssef wrote each of the tunes in collaboration with his participating musicians; still, Street Of Minarets comes off as a cohesive and distinctive effort that will repay repeated listens.

As Youssef told The Irish Times in 2015, “Jazz changed my life. It was like, this sounds like music that allows me to be myself. Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, all those people. Even now they are still inspiring me. They sound like they do because they lived it. If you are a classical composer, you have to study all your life to be able to get there. But if you are a jazz musician, it’s your destiny and that’s it. Billie Holiday didn’t study singing; she was born like that.” Street Of Minarets is jazz from the souk, with an oud in hand.

— Mark Hanser

Tagged: A Little Prayer, and Spain, Andrea Riseborough, Angus MacLachlan, Anna Diop, Celia Weston, David Strathairn, De’Shawn Charles Winslow, Decent People, Dhafer Youssef, Food, Francois-Xavier Roth, Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project, Hank Willis Thomas, Hélène Jawhara Piñer, Jews, Jonathan Blumhofer, Laura Mora Ortega, Les Nuits de Paris, Les Siècles, Nanny, Nikki Giovanni, Nikyatu Jusu, Street Of Minarets, Susan Miron, The Art Ensemble of Chicago, The Embrace, The Kings of the World, The Sixth Decade from Paris to Paris, To Leslie

Regarding “The Embrace”: This public art piece for sure exudes controversy. I can certainly see why there are people on both sides of the debate, and your article was well written without strongly taking sides.

Looking at “The Embrace,” Its location in front of Tremont on the Common residential building seems to try and fail to deal with the scale/height. Crowd-sourcing public sculpture –what could go wrong? I agree that figurative works are more difficult–look at the Boston Women’s Memorial on Commonwealth Avenue–awful , but still.

I think something more elegant and restrained – like the very restrained 911 memorial in the public garden could have been very moving. Or perhaps, just another special location, like the Holocaust Memorial near Faneuil Hall.