Poetry Review: “Places of Permanent Shade” – The Work and Echo of Creation

By Leigh Rastivo

This staunchly eclectic collection is also fiercely focused, unified by the fact that regardless of the subject, the poet never blinks, never looks away, never hesitates to name the pain.

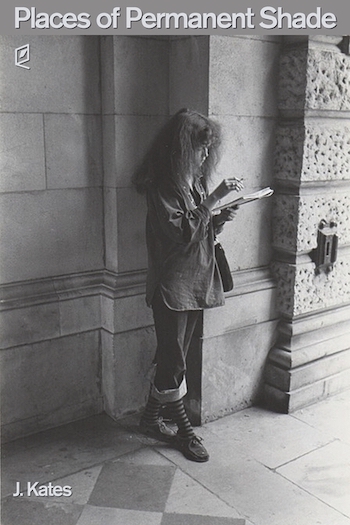

Places of Permanent Shade by J. Kates. Accents Publishing, 83 pages, $17.

J. Kates’ Places of Permanent Shade explores big ideas alongside the commonplace, refusing to limit the scope of its lens. In terms of topics, the collection tackles everything from Monet’s cataracts to an Innuit sea goddess to leaky faucets, and it does so in varying styles and tones. There are found poems, humorous poems, poems that grieve — there is even a macho poem about chopping wood. And yet, this staunchly eclectic collection is also fiercely focused, unified by the fact that regardless of the subject, the poet never blinks, never looks away, never hesitates to name the pain. J. Kates is paying attention in the exact sense of that phrase — doling out perception like currency, showing us that something is spent when we bother to unearth the truth.

J. Kates’ Places of Permanent Shade explores big ideas alongside the commonplace, refusing to limit the scope of its lens. In terms of topics, the collection tackles everything from Monet’s cataracts to an Innuit sea goddess to leaky faucets, and it does so in varying styles and tones. There are found poems, humorous poems, poems that grieve — there is even a macho poem about chopping wood. And yet, this staunchly eclectic collection is also fiercely focused, unified by the fact that regardless of the subject, the poet never blinks, never looks away, never hesitates to name the pain. J. Kates is paying attention in the exact sense of that phrase — doling out perception like currency, showing us that something is spent when we bother to unearth the truth.

Right away, Kates all but declares this intention to wrangle deeper meaning despite the cost. The collection begins with the epigraphical poem “Words,” where language is personified as “always a beast” to “bring to heel.” This grounds the abstract exercise of searching for words in the tangible visual of tracking and hunting: words “snarl and pace the line…” and the poet “[sets] out/decoys to bring them close enough to shoot” or else he waits in the reeds “for a word to swallow the hook.” The poem’s final image is a word/fish “flap gasping in the scupper. /Dying…” Finally, “a small mouth bleeds.” We see a living entity drained in service to writing.

“Words” is followed by “Falling,” another poem about the use of language, although rather than describing a relationship with writing, “Falling” demonstrates the act. Lean at just nine lines (twenty-six words in all), “Falling” flexes considerable literary muscle. It is crammed with connotations and, based on its clever form, can be read in at least three ways. In one reading, if we follow the “falling is” sentence structure from the title onwards, we are given novel definitions of falling: falling “is bowing to gravity/steadily forward” and falling “is walking/upward” and falling “is flying/in the assurance of getting caught” and falling “is diving/everywhere at once.” Conversely, another look might prioritize the poem’s couplet structure, reading each couplet’s first line clause as a modifier for the second line adjective, so that “steadily forward/is walking” and “upward/is flying” and so on:

FALLING

is bowing to gravity

steadily forward

is walking

upward

is flying

in the assurance of being caught

is diving

everywhere at once

is keeping in balance

Thus, with its brilliant enjambment, “Falling” further emphasizes the theme of “Words” — that is the layered meaning of words — the reward — becomes ours when we endeavor to engage.

Throughout the collection’s five sections, Places of Permanent Shade holds steady to these initial literary values — Kates commands language, at times playfully and always thoughtfully. More impressively, straightforward word choices lie behind the poems’ luminous diction. The result is a seamlessness — even after telling us that it is a chase, Kates makes phraseology look easy. Perhaps that is unsurprising, considering he is not only a poet who has honed the craft for decades; Kates is also an award-winning literary translator of Russian, French, Latin American, and Peninsular Spanish poetry, accustomed to the nuances of lingual interpretation. This specialization is demonstrated a few times in Places of Permanent Shade, including in “Spleen,” a poem which appears both in English and French. “Spleen” is a sullen complaint about the banality of isolation found in any given city. Effectively underscoring the predictability of gloom, Kates repeats key words in several places: the cities “…all have weather/and weathered ruins” and “Old bricks poke like old bones” “in a dismal city in a dismal climate.”

There is more brooding in the nature poems, especially those about walking the land, knowing the land, and owning the land. In “Possession,” the narrator’s disenchantment with cleaning up his property after storms becomes a metaphor for “…having to face the past/rather than looking forward.” Similarly, in “Betrayals,” he frets about working a homestead for thirty years only to “…let it go, season by season, till/it [isn’t] worth the work.” This altered relationship with property is palpable; the narrator’s familiarity with the land turns into a negative: “I walk these woods in confidence/ that borders close to boredom.” And the collection’s title poem “Places of Permanent Shade” extends the discontent to human relationships, as a couple hikes down a mountain after not making it to the top. Their failure to make the summit is equated with their failure to fall in love — another disappointment of the day. Their time spent together is deemed a waste via a lovely, simple sentence that applies both to the hike and the affair: “We dawdled too long at the scant timberline.”

Kates’ penchant to harness the uncomplicated or unexpected yet utterly suited word or phrase is best displayed in several smaller poems that dramatize the ordinary, often through imagery or characterizations of the inanimate. A few of many examples: “Bones rise/under the skin/like sharks/in shallow water” in the poem “The Wrist.” In “A Lake in the Woods,” the view of a distant town is “where smoke/lifts the sky on its shoulders over the hill.” In “The Faucet,” which is told from the defiant faucet’s point of view, a dripping leak is the narrator’s “…way/to keep the water running/one tear at a time.”

In each of these instances, some supposedly mundane aspect of experience is either heightened emotionally or connected to another vivid experience and is thus essentially re-created. Interestingly, the notion of creation as re-creation is explicit in the poem “Critique.” Here Kates presents what he sees as the common standard: poems should at least make “a good prose sense.” He then rephrases and deepens the principle: “It is the world we echo that we create.” That is: poems represent what already exists, and thus, they must echo the world and be based in its reality; but once the echo is uttered, poets then further conceive the represented world by revealing its underlying implications.

Places of Permanent Shade ends with the poem “Three Weeks.” The “wind has shifted” and there is “a funeral to be arranged…” The narrator walks out into the night “to name the old stars/in their new settings” — a task that he will accomplish “without the help of/imagination.” Perhaps that is because the stars are already named. They exist, but not as before. Do they symbolize the newly deceased? Or maybe the stars are waiting for the narrator to perform the labor of echo and revelation, finding the words that highlight a not-yet-considered significance. The latter would be an apt conclusion to a collection so radiantly wrought.

Leigh Rastivo is a fiction writer, reviewer, and essayist. She was recently accepted at the Under the Volcano international residency where she will present and hone two novels (one literary and one speculative). Leigh’s shorter fiction has been published or is forthcoming in several journals, including the MicroLit Almanac and L’Esprit Literary Review.

Tagged: Accents Publishing, J Kates, James Kates, Places of Permanent Shade