Translator Interview: John Taylor on Philippe Jaccottet

By Bill Marx

“We have entered an age of unequivocal partisan discourse, of linguistic robotization, of tiny symbols standing for complex emotions. In total contrast to this, Philippe Jaccottet’s writing constantly shows nuance, attentiveness, perseverance, circumspection, and a genuine quest for essential truths.”

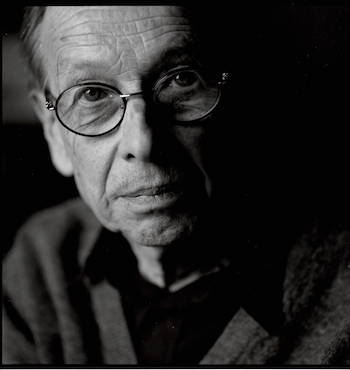

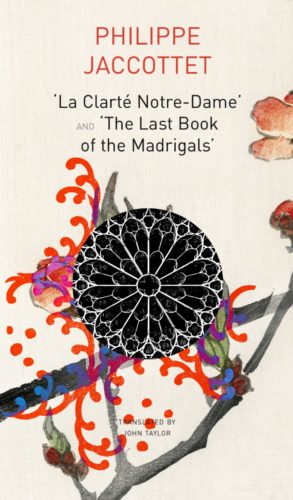

Poet Philippe Jaccottet. Photo: Felix von Muralt

The late Swiss writer Philippe Jaccottet, winner of the Petrarch Prize, the Prix Goncourt, and the Schiller Prize, completed two manuscripts-in-progress in his 96th and final year, with the help of the poet José-Flore Tappy. La Clarté Notre-Dame, a sequence of prose selections, and The Last Book of the Madrigals, a gathering of verse, both translated by John Taylor, have just been published by Seagull Books in a single volume. Taylor has translated a number of other works by Jaccottet for Seagull, including Patches of Sunlight, or of Shadow, The Pilgrim’s Bowl, and A Calm Fire.

A major French poet, Jaccottet was one of only three poets to be published in the classic Pléiade collection during his lifetime. For him, poetry sprang from “an attentiveness to the visible that is so deep that it necessarily runs up against its limits, against the unlimited that the visible seems to contain or to hide, to refuse or to reveal.” His was a vision of bedeviling but graceful elusiveness, dedicated to intimating what lies beyond our perceptions of nature. Poetry can evoke an intense experience of the immediate — where beauty and death, light and shadow, joy and sorrow coexist — but words inevitably fall short. For all its mimetic power, language is imprecise, ephemeral. Articulations of wonder are doomed to fail. But, by concentrating with preternatural sensitivity on what’s here, poetry can point to what’s not here, to what lies beyond, the nothingness/somethingness of the “unlimited.”

And there is a nurturing strength in that struggle. In a tribute to Jaccottet after his death in 2021, Taylor wrote that “his writings show us how to invert our hesitations, our trembling, our distress into worthy, beneficial sources that can open once again like a flower after the night, after the early morning frost.” I was curious about what it meant to Taylor to translate Jaccottet, and I turned to Arts Fuse contributor Tess Lewis, translator of three volumes of Jaccottet’s notebooks (Seedtime, The Second Seedtime, and Seedtime III) for the expert questions below.

Arts Fuse: Over a lifetime of writing in multiple genres, precision of observation and description was, for Jaccottet, a way of understanding the world. What techniques did you lean on or develop in order to render his nuanced investigation of nature, art, and emotions?

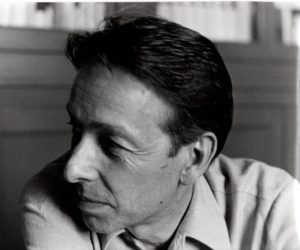

Poet and translator John Taylor. Photo: Françoise Daviet-Taylor

John Taylor: Philippe Jaccottet was a close observer of nature, but something deeper and more essential than perception per se is involved in his literary and philosophical approach. This is the dimension that engaged me from the onset with his oeuvre, when I started reading it, and reviewing it, in the mid-1990s. He outlines this dimension in Ponge, Pastures, Prairies (Black Square Editions), his memoir of his friendship with the poet Francis Ponge, known for his evocations of the “thing-in-itself.” In that book, Jaccottet shows how, over the years, and without losing his affection for the man, his own poetics diverged from those of the author of Partisan of Things. More than an observer, Jaccottet is an incessant questioner of man’s relationship to nature, to the cosmos, to being; and as a consequence of this vantage point, what is at stake in his writings, much more than objective description, is the relationship of the self, and language, to the experience of reality: how to find the right words for a moment experienced suddenly as encompassing an enigma or inducing astonishment.

These rare moments of marvel unexpectedly occur when Jaccottet finds himself in front of, for example, peonies, wild carrots, kingfishers, robins, bindweed, a quince orchard, a cherry tree, and the streams near the village of Grignan, in the south of France, where he lived most of his life. In brief, Jaccottet takes off in a more subjective and philosophical direction, and is driven by a different stylistic imperative, than that explored by Ponge in his poems, “proêmes,” and extensive writings about how he composed them. In contrast, Jaccottet describes and interrogates his “glimpses” of something that fleetingly seems to surpass pure materiality — the “thing-in-itself” — as well as the self. And yet, he cautions almost as soon: illusion might well be involved in these perceptions, creating in him a deceiving impression of transcendence.

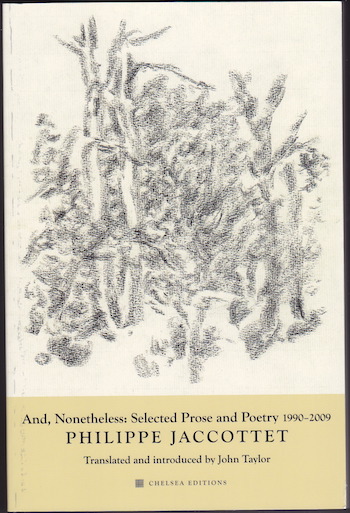

Moreover, he characteristically weaves literary allusions and quotations into his prose pieces, which were the first of his texts that I translated — for the volume And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry 1990-2007 (Chelsea Editions), published in 2011. He uses the insights of other poets to stimulate his own reflections about what has caught his attention as if by a kind of mysterious “beckoning”—rather like the leitmotiv of the monastery bell in his last book, La Clarté Notre-Dame (Seagull Books). Such are the issues, linking perception, thought, emotion as well as critical reading, and their formulation in scrupulously crafted language, that run through Jaccottet’s texts. The translator progresses slowly through this exacting prose that takes nothing for granted, with its close observation, cogitation, literary references, and subtle soul-searching. When considering how this remarkable sensibility can be rendered into English, one must carefully examine and comprehend why there are numerous verbs in conditional tenses, several forms of negations, sentences with as many as three or four semicolons, words like “perhaps” or “almost” (or one of their synonyms) immediately attenuating what is asserted, and imagistic similes — “like” and “as” crop up frequently — revolving around, or targeting, the subject matter from the periphery. Jaccottet combines these stylistic elements into compelling narratives of his quest.

AF: And how did translating his explorations of the visual world affect your own perception of the natural world and art?

AF: And how did translating his explorations of the visual world affect your own perception of the natural world and art?

Taylor: For decades now, I have spent many pleasurable moments identifying wildflowers during short summer stays in the French Alps, often in the village of Bessans. Such an activity is remotely related to what I have just outlined, with respect to Jaccottet’s poetics, in that it demands precise observation (but also the use of specialized botany manuals). The activity has informed several of my own writings. Jaccottet may well have practiced such observation and identification as well, for his poet-friend Pierre-Albert Jourdan reports, in The Straw Sandals (Chelsea Editions), that he showed up one day at the Jaccottets’ house and noticed, on a table, a volume of Novalis and a birdwatcher’s manual. And there is a photo, in the exhibition catalogue Jaccottet poète (Centre de recherches sur les lettres romanes, University of Lausanne), of Jaccottet and his childhood friend, the artist Jean-Claude Hesselbarth, sitting in a field as adults and intensely identifying wildflowers or perhaps insects, with a manual in the latter’s hand.

In any event, I can say that Jaccottet’s poems and prose texts, beginning with a period well before I began to translate his work, constantly accompany my walks and hikes. His way of looking at and thinking about the world continue to guide me beyond mere examination or contemplation, that is, ever further into the mystery of what perhaps lies beyond the appearances that I am observing; at the same time, his example reminds me to be wary of what I might be extrapolating from admiration. In fact, my first stabs at translating him took place one summer in that same mountain village, Bessans. At the time, I was also writing a series of short texts, based on my thoughts and observations during my hikes, that would later be gathered into a bilingual book in France, Boire à la source / Drink from the Source (Éditions Voix d’encre), and later incorporated into a longer American book, Grassy Stairways (The MadHat Press). For about three weeks, every day was filled with hiking, observing, writing, and translating Jaccottet. I remember confirming with him, a little later, that his French word “fontaines,” which appears in some of his texts, indeed referred, not to “fountains,” but instead to the “watering troughs,” filled by water captured from rivulets, that I kept coming across in the Alpine cow pastures.

One last word about mountains. With a few exceptions, Jaccottet, who was born and raised in Switzerland and who thereafter long lived in France near mountains, emphasized the viewpoint that if there were indeed anything of a transcendent nature to be found beyond appearances, beyond the “threshold,” as he sometimes phrased it, then we should look for it, not on lofty peaks (which can easily foster romantic exaltation and therefore illusions in us), but “down low” among simple, modest, ordinary natural things. This is one of the great lessons of his books.

AF: In one of his Seedtime entries from 1966 Jaccottet investigates his ambivalence towards rhyme:

“The conflict between rhyme and ‘truth.’ At times I want rhyme in order to ensure the poem’s coherence; sometimes, when it makes me say something other than what I should, I abandon rhyme, which is not satisfactory either.”

How did you navigate formal elements like rhyme and meter that often don’t map elegantly or persuasively from French into English?

Philippe Jaccottet in 1970. Photo: Richard Salesses

Taylor: Actually, my translations of Jaccottet’s work begin with the books that represent his “turn” from verse poetry, a period starting in 1990 with the publication of Cahier de verdure (titled Notebook of Greenery and comprised in the aforementioned Chelsea Editions volume). Beginning with that book, and with relatively few verse poems thereafter (but indeed with the major exception of The Last Book of the Madrigals just published by Seagull Books), he devotes himself almost exclusively to prose. When Jaccottet and I first discussed the possibility of my translating some of his writing, in 2009, he asked me to begin with Notebook of Greenery, adding that he feared that its particular kind of prose might be misunderstood in the Anglo-American literary world. Notebook of Greenery still includes some poems, but they often intentionally “fall into prose,” as Nerval puts it, or, at least, greatly mitigate formal qualities such as rhyme and meter.

By this period in his life, Jaccottet is working with hybrid forms: verse poems that approach prose or display fragmentation; poetic prose texts that cannot be called “prose poems”; narratives that are not “short stories”; there is no “fiction,” but nor is there “nonfiction” in the Anglo-American sense of the term. I think that this “conflict between rhyme and truth,” which you have rightly pointed out, definitely becomes a broader and deeper issue for him with Notebook of Greenery and the post-1990 volumes: After Many Years, And, Nonetheless, These Slight Noises, and two similar texts, Clouds and Earth Color, which I also translated for the Chelsea Editions volume, as well as with La Clarté Notre-Dame. In his attempt to penetrate the true nature of appearances, and in his circumspection about the very validity or conditions of such a quest, Jaccottet becomes even more skeptical of rhetorical ornamentation, a propensity already strongly expressed in his moving long poem from 1969, Leçons (Learning…, translated by Mark Treharne for the Delos Press), about the death of his father-in-law. He is wary of stylistic mellifluousness in which sound might over-envelop, dilute, or deviate meaning; instead, he strives for a scrupulous exactness of expression, a precise, ever-measured transcription of his meditations on such and such a subject matter. It follows that his writing is also “about” the purpose of writing, especially—this aspect of his poetics must not be overlooked — in a world full of brutality and misery. This is one of the themes of La Clarté Notre-Dame, with its recurrent image of prisoners being tortured in Syria.

AF: Jaccottet published one novel, Obscurity, in 1961. Why didn’t he write others? And how does this volume about the ferocity of disillusionment fit into his body of work?

AF: Jaccottet published one novel, Obscurity, in 1961. Why didn’t he write others? And how does this volume about the ferocity of disillusionment fit into his body of work?

Taylor: It has long seemed to me that Jaccottet’s only novel, Obscurité (translated as Obscurity by Tess Lewis for Seagull Books) has been relatively neglected. Perhaps this is because Obscurity is a fictional narrative, whereas Jaccottet’s poetry and prose texts grapple with reality and with the difficulties of seeing it for what it is, without any wishful thinking, false spiritual hopes, romantic effusion or, indeed, “fictionalizing.” Moreover, Obscurity aligns various events as it relates a story, whereas the writer’s subsequent works, be they in verse or in prose, tend to focus on a single exceptional event, a literally extraordinary perception. And yet this gripping novel puts forth at least two of his key themes: his search for what other poets and writers can teach him about “how to live” and his own struggle, like that of the main character — the philosopher-mentor — with the terrifying and paralyzing thought of death.

As Montaigne pointed out, “philosophizing is learning how to die.” Here, the main character, whose thought and personality have marked the lives and minds of his students, including the narrator (who has returned from a long stay abroad and has tracked down his mentor’s whereabouts), has now withdrawn into a kind of fright-ridden, nihilistic revolt against what is inevitable: his own demise. What, then, the narrator wonders, was the veracity of the lofty thoughts taught to him by the philosopher if they have led to such an end? Were they mere empty words? And if so, what are the true words that can be applied to the vision of death, to its brutal factuality? I’ve mentioned the importance of his long-poem Leçons, which seeks to come to terms with the devastating fact of a loved one’s death. Published eight years before that work, Obscurity already explores the same central issue, which engages the very foundations of writing and which Jaccottet will continue to analyze through his final book, La Clarté Notre-Dame.

AF: Music has been a central inspiration and reference point for Jaccottet’s poetry and prose, most obviously in The Last Book of the Madrigals. How does this volume echo or engage with madrigals in general and Monteverdi’s in particular?

Taylor: Jaccottet was a great lover of early forms of music such as Gregorian chants, Monteverdi’s madrigals, and baroque music. However, I would say that, as far as his own writing processes are concerned, it is the love-oriented lyrics of the madrigals that most engaged him, even as he was also a reader of Dante’s Vita Nuova, with its haunting remembrance of a likewise “glimpsed” Beatrice, whose appearances in the poet’s life are more like apparitions, even hallucinations. The Last Book of the Madrigals is the culmination of, and even a more forthright expression of, a thematic undercurrent in his writing: amorous attraction, even erotic desire, in the face of ephemerality and inevitable death — a preeminent baroque conceit. Critics have rarely emphasized this aspect, but it is there, sometimes half-disclosed in the way he evokes natural elements; in La Clarté Notre-Dame, it is more explicit, as when he writes of his sleeping wife and their bed; as for The Last Book of the Madrigals, as he grapples with despair in the face of death, we find, for example, the theme of love and happiness in his reflections on Dante’s poem about a boat ride with Guido Cavalcanti and another friend as well as with their three girlfriends. I would argue that for Jaccottet, sensuality — highly conscious sensate experience in the broadest sense of the term — traces out a kind of bridge between subject and object. Ultimately, this is the same kind of separation theorized, but differently, by Ponge.

Philippe Jaccottet in his study in Grignan. Photo: ©Philippe-Jaccottet-Estate

AF: Monteverdi was a great musical innovator. Do you see a comparable tradition-expanding approach in Jaccottet’s writing?

Taylor: Jaccottet was also a wide-ranging, extremely perceptive critic of European literature, and a connoisseur of forms. However, it seems to me that what most absorbed him were not literary forms or traditions, but instead the innermost aims and purposes of writing and the ways by which other poets and writers from various cultures and centuries carried out the same quest. Once, for example, we spoke about haiku. I quipped that I was currently on a “haiku cure” in the hopes of subsequently learning to form images more concisely. He said that he had gone through similar periods in which he had read, and sometimes translated, lots of haiku. I then asked him if the haiku form interested him, given the fact that some of his poems are quite short. He replied that it was the problem of understanding the scope, the possibilities, and, once again, the “validity” of imagery that preoccupied him.

Similarly, although it can be said that Jaccottet innovates on the tradition of the madrigals with this final volume, I would suggest that the deepest undercurrents in his poetry and prose, from the beginning, especially stem from his lifelong dialogue with the works of his mentor, Gustave Roud, and with the poetry of Rilke and Hölderlin. By this, I am thinking not of the forms employed and invented by these three masters, but rather of the themes and meanings formulated in their oeuvres. Jaccottet studied their works in their finest details, faced up to the challenges they raised, and responded to them with his own unique sensibility. By the way, in La Clarté Notre-Dame, Jaccottet expresses the regret that he should have paid even more attention, comparatively, to Hölderlin than to Rilke.

AF:You have musicians in your close family, as did Jaccottet. What influences of music do you find in his writing?

Taylor: Philippe Jaccottet and my son Justin Taylor have a favorite instrument in common: the harpsichord. Besides being a connoisseur of classical music, Jaccottet was a fine amateur harpsichordist. In his living room, he had a harpsichord built by his close friend Wayland Dobson, who appears in These Slight Noises and Patches of Sunlight, or of Shadow (Seagull Books). This being said, as I have already suggested in regard to The Last Book of the Madrigals, I remain skeptical about direct musical influences on his writing style, both in his prose and poetry.

Are there really genuine bridges, which are not mere metaphors or similes, between the two art forms? I am not at all sure that one can transmute solfeggio into prosody, “musicality” in music into “musicality” in style. Instead, I would argue that his prosody is informed by his vast reading in the literatures of several languages — he was a genuine European man of letters — and specifically in his schooling not only in classical French literature but also in Latin and Greek. His early poems were written in alexandrines. It’s true that listening to music stimulated his reverie, as he explains in a long passage, dated 21 September 2002, near the end of Patches of Sunlight, or of Shadow. The passage begins: “Yesterday evening, while listening again to Bach’s English Suites played by Leonhardt, I once again find myself carried off by the élan of these pieces, which is not a ‘dancing’ élan despite their title and the origin of their forms; I think in turn of mobile houses, of mobile figures, of ornate time, whose structures would have become visible in the transparency of hearing; and also, because of the special sonority of the harpsichord, as I had already done so in my poems ‘to Henry Purcell,’ of dialogues between icy peaks exchanging their scintillating reflections. At the same time, outside, I see the recently denuded branches of the fig tree…” Let me end the quotation here, with this reminder (which the poet makes to himself) to focus on still another “beckoning” emitted by something in the real world; such perceptions (here, of the fig tree) constitute the genuine stimuli to his more prolonged meditations and therefore are the true “notes” moving him to compose poems and prose pieces. These spontaneous jotted-down perceptions were like “seeds” for him, as the title of his three-volume series of notebooks, Seedtime (translated by Tess Lewis for Seagull Books) specifies.

AF: Jaccottet was a masterful and accomplished translator. The literary masterpieces he translated into French from German, Italian, Ancient Greek, Spanish, Russian, and, with the help of cribs, from Japanese and Czech, were immensely varied in tone, register, and formal discipline or looseness and came from disparate literary traditions. His touchstone authors are a particularly strong presence in this volume. Did you return to the originals or to his translations of these writers when having to convey allusions or references to their poems in Jaccottet’s madrigaux?

Taylor: In The Last Book of the Madrigals, as well as in his earlier works, Jaccottet nearly always offers his own French translations of the poems or prose passages that he cites from foreign authors. I know German and Italian, as well as Modern Greek, and so for those languages I always go back to the original texts and, in most cases, offer my own version — though on occasion I borrow an extant translation that is perfect for my purposes. My guiding rule is to provide, or find, a smooth literal translation, with the original meaning conveyed as accurately as possible.

On a few occasions, Jaccottet helped me to find the exact references to the originals, such as for a few lines from a poem by Goethe that was not otherwise introduced and thus difficult to locate. And his son Antoine helped me track down the English versions, by R.H. Blyth, on which Jaccottet had based his French translations of the Japanese haiku included in Patches of Sunlight, or of Shadow. For a language like Spanish, which I do not know very well, I nonetheless go back to the original texts and at the same time search, among extant translations, for an authoritative, but not “inventive,” “poetic” or “free”— adjectives that make me smile — interpretation that I can cite in my translation. Jaccottet taught himself Russian in order to read and translate Osip Mandelstam. For that language, which I do not know, I seek out extant translations.

The languages that I have cited here, along with Latin and ancient Greek, are those with which Jaccottet worked directly, without cribs, most of the time. By the way, going back to the original texts also raised a few editorial issues that I discussed with him. For a prose piece in the Notes from the Ravine section of These Slight Noises, Jaccottet cites a poem by Eugenio Montale, with the lines “Fu dove il ponte di legno / mette a Porto Corsini sul mare alto / e rari uomini, quasi immoti, affonano / o salpano le reti…”, which in Jonathan Galassi’s translation (in Montale’s Collected Poems 1920-1954 at Farrar, Straus and Giroux) reads: “It was where the wooden bridge / spans the high tide at Porto Corsini / and a few men, almost motionless, / sink or haul in their nets…” In his text, Jaccottet quotes the poem in Italian only, and then adds: “A scene from the past, yet we do not know precisely which one, and it is linked to a specific place — which I do not know either, nor need to know — in Italy, on a lake- or sea-shore.” Because Montale’s poem is clearly set on a seashore, I asked Jaccottet if he would like to delete, in the bilingual Chelsea Editions volume, the reference to a “lakeshore.” He explained, however, that what was important to him was how he remembered a poem, its associations. In a personal letter dated 27 November 2010, he told me that his recollection of the opening lines had also given him this image and this “sentiment of the other shore” — once again, an allusion to what perhaps lies beyond a “threshold.” And so he maintained the reference, as well as in the 2014 Gallimard-Pléiade edition of his collected writings, a meticulously edited and thoroughly resourceful volume overseen by the Swiss poet José-Flore Tappy, who was also the close friend who helped Jaccottet to put together, before he died in 2021, the manuscripts of La Clarté Notre-Dame and The Last Book of the Madrigals.

AF: Your published translations of Jaccottet’s work span more than a decade, beginning with the Chelsea Editions volume, and your critical writings about his poetry go back much earlier, to the mid-1990s. Did your way of translating him and/or understanding of what translation can and cannot do change with your journey through his writing?

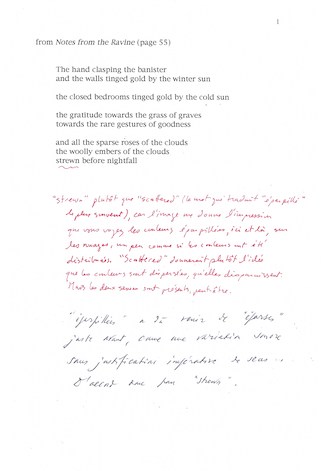

A manuscript page annotated by John Taylor and Philippe Jaccottet.

Taylor: If the Chelsea Editions volume, which is now out of print, is republished one day, as I hope, I will certainly go through the translations again, all the while keeping in mind that a translator cannot always recover the intricate thinking — the weighing of pros and cons with respect to one solution as opposed to another one — that enabled him or her to come to a decision about how to render a given word, phrase, line, or sentence. And for that particular book, most of the difficult issues were discussed with the poet himself. Jaccottet had neither a computer nor email, so I would send him the nearly definitive drafts of my translations, noting in the margins a question or two and, in the case of a thorny choice, explaining which English word struck me as the most appropriate one and soliciting his opinion. He was very generous in this regard. He would mail my manuscripts back to me after annotating them, sometimes adding background information about why he had written the sentence or line in the way that he had; or he would telephone me and we would discuss the problem that way.

At the same time, experience (especially with several books by the same author) helps the translator to see certain recurrent problems more clearly. One of the challenges of translating French poetry or poetic prose into English is what I call the “semantic resonance” of French words with respect to English words. To state the dichotomy simply, English nouns and verbs often possess a matter-of-factness that enables them to name a thing or an action quite precisely, whereas the comparative semantic range of equivalent French nouns and verbs can cover more than one thing or evoke an action both concretely and with various figurative senses that are not always as forcibly present in English.

This potency of French becomes especially important in several kinds of poetry and in high literary styles such as Jaccottet’s. In fact, it is already perceptible in the example that I mentioned earlier: the French “fontaine,” with its factuality (in the context of mountain agriculture) and its many metaphorical extensions, as opposed to the arguably more factual English “fountain” (despite its own inherent symbolism) and especially “watering trough.” For a translator, the choices are not always easy, to say the least, for there are sometimes two or three English candidates for a single “resonant” French term. Semantic resonance underlies the long-standing “Racine vs. Shakespeare” debate, which fascinated Stendhal and many other French authors, and it is a question which Yves Bonnefoy considered in his essays about translating Shakespeare. As a translator, my first prolonged confrontation with semantic resonance was with the aphoristic prose of Pierre-Albert Jourdan. Over the years, while translating Jaccottet and other French-language poets (I’m thinking in particular of Pierre Chappuis, Pierre Voélin, José-Flore Tappy, and Georges Perros), not to mention the Italian poetry of Franca Mancinelli and Lorenzo Calogero (both of whose verse employs words with similar resonance or, as Mancinelli phrases it, “openness”), I hope that I have sharpened my skill to deal with this essential richness of those two languages.

AF:Why do you return to Jaccottet’s work today? What does it have to communicate to new generations of readers?

AF:Why do you return to Jaccottet’s work today? What does it have to communicate to new generations of readers?

Taylor: We have entered an age of unequivocal partisan discourse, of linguistic robotization, of tiny symbols standing for complex emotions. In total contrast to this, Jaccottet’s writing constantly shows nuance, attentiveness, perseverance, circumspection, and a genuine quest for essential truths. His hesitations and doubts are salutary because they bring us to a halt and help us to observe and ponder anew, sometimes against our own preconceptions and wishful thinking, as we learn to cast away chimeras but also not to abandon all hopes. His stylistic scruples are employed to determine the reality of, and the illusions behind, what we have experienced, that is, whether the sentiment or the perception, which has seemed so real to us, so literally “wonderful” or “mysterious,” is truly founded, and grounded (literally, on the earth at our feet), whether what has appeared “beyond the threshold” was merely deceiving us with mirages and false aspirations, or whether, in the final reckoning, “something else” has indeed been glimpsed and is more than a passing apparition.

Jaccottet’s last words in La Clarté Notre-Dame echo his earlier title And, Nonetheless. As he meditates on Hölderlin’s great poem “Patmos,” he courageously leaves the door open and his lifelong questions unanswered: “Recalling these lines of verse, with everything that the mere name of ‘Patmos’ arouses in me, including the memory of Saint John who would have received I no longer know what illumination there, and thinking of those very steep mountains separated by an abyss, I would almost feel tempted to ask in turn for both ‘innocent water’ and wings for an unthinkable crossing, and yet. . .”

(This interview with Taylor was carried out by e-mail between October 6 and 21, 2022.)

John Taylor, born in Des Moines in 1952, has lived in France since 1977. As a literary critic and translator, he has long been one of the essential bridges between European literature and English-speaking countries. His translations of Italian, Modern Greek, and especially French-language literature include books by Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre Voélin, Catherine Colomb, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Pierre Chappuis, Georges Perros, José-Flore Tappy, Elias Petropoulos, Elias Papadimitrakopoulos, Franca Mancinelli, Alfredo de Palchi, and Lorenzo Calogero. He is also the author of several volumes of short prose and poetry, most recently The Dark Brightness (Xenos Books, 2017), Grassy Stairways (The MadHat Press, 2017), Remembrance of Water & Twenty-Five Trees (The Bitter Oleander Press, 2018), and a “double book” co-authored with the Swiss poet Pierre Chappuis, A Notebook of Clouds & A Notebook of Ridges (The Fortnightly Review Press, 2018).

Tagged: Bill-Marx, French poetry, John Taylor, La Clarté Notre-Dame, Obscurity, Philippe Jaccottet, Seagull Books

Thanks for this interview. In truth, I knew next to nothing about Philippe Jaccottet’s work, and even less about John Taylor. Doing what a good review can do, this piece peeled up a corner to give me a glimpse of something I was largely unaware of–and points toward where I can find the work itself.

To vary the phrase of Montaigne quoted in the piece– “philosophizing is learning how to die”–reading is learning how to see more before we die.

Excellent, thoughtful, deeply informed and layered piece. I would have enjoyed more quotes, perhaps side-by-sides, from Jaccottet’s work. How wonderful– and maybe a little intimidating — for a translator to be able to work in real time collaboration with ‘his’ poet. Thank you, John Taylor.