Visual Arts Feature: Leonard Cohen — Peering Behind the Public Persona

By Robert Israel

Despite Leonard Cohen’s outward humility, he was, in fact, an artist who very much cultivated acclaim, and wanted that attention to endure.

“Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows,” Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), 317 Dundas St. W., Toronto, Ontario, through April 10, 2023.

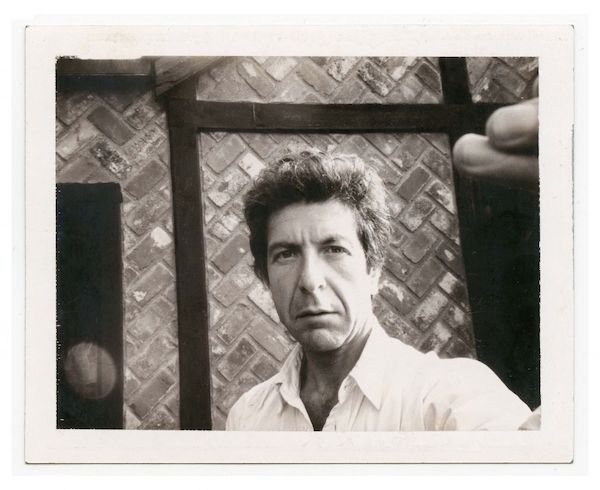

Leonard Cohen, Self-Portrait, 1979. Instant print (Polaroid Type 667). Overall: 10.8 × 8.3 cm. © Leonard Cohen Family Trust

Flashback: Six years ago, I hotfooted it to Toronto. While I’d visited the city before to review Robert Lepage’s one-man show, and to write about other performances and art exhibits, this time I was seeking refuge from the onset of Trumpism. That’s when I got hit with another whammy. Reading the Toronto Star, slipped under my hotel room door overnight, I learned that Canadian singer/songwriter and author Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) had died at age 82. Now I knew what Cohen meant when he said he felt “as cold as a new razor blade.”

Flash forward: Fearing Trump’s endorsed slate of election deniers might win office and further erode our democracy, I returned this year to Toronto to brace for what looked to be a political tsunami back home. But that storm never happened; more encouraging election results prevailed. I turned to Cohen’s music, particularly his song “Democracy” to raise my spirits higher: “It’s coming to America first/The cradle of the best and of the worst/It’s here they got the range/And the machinery of change/Democracy is coming to the USA,” he wrote.

Comparisons to Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas are obvious: both poets affirm American democracy.

“[‘Democracy’ is] a song of deep intimacy and affirmation of the experiment of democracy in this country,” Cohen said in an interview. “That this is really where the experiment is unfolding. This is really where the races confront one another, where the classes, where the genders, where even the sexual orientations confront one another. This is the real laboratory of democracy.”

Yet I wondered how Cohen might respond if asked about today’s climate threats, the loss in the US of a woman’s right to choose, the conflagration in the Ukraine, Trump’s return to the hustings. Would Cohen still be as hopeful?

Many turn to and draw inspiration from the engagingly personal aspects of Cohen’s work. This year there’s been a spate of new releases: a documentary film on the making of his song “Hallelujah”; an album, Here It Is, featuring covers of his songs by Mavis Staples, Norah Jones, Iggy Pop, and Peter Gabriel; the publication of A Ballet of Lepers, a collection of his early writings (Arts Fuse review); and a recently opened exhibit, “Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows,” at Toronto’s Art Gallery Ontario (AGO).

While in Toronto, to learn more about the AGO exhibit and how it might shed light on Cohen’s enduring influence, I spoke with Julian Cox, AGO’s deputy director and chief curator. He explained that, despite Cohen’s outward humility, he was, in fact, an artist who very much cultivated acclaim, and wanted that attention to endure.

“He was quite young at the time, around 29 or 30 years old, when he set out to shape his legacy,” Cox explained. “Even at that early age, he knew he wanted to leave his mark. So he established his archive at the University of Toronto. That material has only just now become available for public viewing.”

AGO, partnering with Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (Cohen’s hometown), is now expanding our view of Cohen, the man and the artist, with a meticulous chronology of his visual and aural works. Cohen did not set out to become a songwriter. Initially, he saw himself as a poet and novelist. And, in the spirit of his pioneering family, who established one of the largest synagogues in Canada, he yearned to be a macher, an influencer.

“McClelland and Stewart, his publisher in Toronto, issued his early books, including his novels. But Cohen had other loftier aspirations, and that led him toward performance. So he began to develop a public persona,” explained Cox. “He may have struggled with an inner turmoil and numerous anxieties when it came to his live performances, but nonetheless he craved that spotlight.”

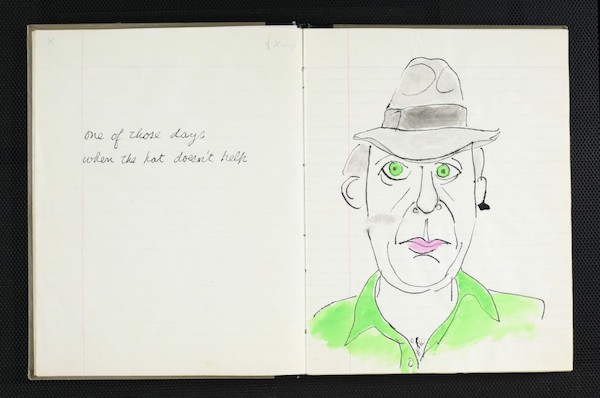

Leonard Cohen, One of Those Days (Watercolor Notebook), 1980-85. © Leonard Cohen Family Trust

The AGO exhibit reveals that Cohen turned to the concert stage because his initial artistic endeavors did not attract the following he craved. His books did not sell. And it didn’t help matters that his publisher, Jack McClelland, deliberately withheld publication of A Ballet of Lepers – only released this year, six years after Cohen’s death — despite Cohen’s repeated attempts to have the book published during his lifetime.

The exhibit follows Cohen after he quit Canada to live in Hydra, an island in Greece, where he was supported by a family inheritance. It was there that he took up with Norwegian expat Marianne (the muse of his song, “So Long, Marianne”) and began writing songs like “Bird on the Wire,” which express his longing for personal liberty. The show also follows the artist’s numerous triumphs and failures in the ensuing years.

“At AGO, visitors have an immersive experience. They hear Cohen’s voice speak about his relationship to performing, view clips of his concerts on three different video screens that create a montage of him and his iconic songs, and see images of his development, many captured by himself,” Cox said.

The curator is referring to Cohen’s obsession with taking Polaroid self-portraits — including snapshots of himself in the nude. Collectively, this plethora of photos reveals a haunting — and haunted — countenance. (Cohen’s struggles with substance abuse and mental health challenges throughout his life have been well documented.) These images were precursors to his numerous drawings, also amply on display. First published in his Book of Longing, his crudely sketched self-portraits — done in ink and watercolor — reveal a man preoccupied with the physical as a mirror of darker, often self-deprecating, moods.

“We also see evidence of his relationships with other artists,” Cox said. “These objects were part of the archives at the University of Toronto that had been held back. They include correspondence from performers like Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez, k.d. lang, and many others.”

Also on display are numerous handwritten drafts of his work, revealing Cohen’s disciplined approach to writing.

“Cohen viewed writing as his job, as labor; he worked painstakingly, and the exhibit shows pages after pages of verses he composed but rejected, before arriving at the finished song,” Cox explained. “For instance, it took Cohen five years to complete ‘Hallelujah,’ one of his best known works, which, at one point, had over 50 stanzas.”

AGO’s Cohen exhibit may indeed travel to other cities, Cox told me, but no dates have been firmed up. Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts has exhibited AGO shows in the past — most notably the photographic exhibit of the work of Holocaust survivor Henryk Ross. When queried, an MFA spokesperson said no plans are afoot.

The exhibit derives its title from one of Cohen’s songs. But the curator noted an additional meaning.

“Audiences feel they know Leonard Cohen,” Cox said. “They respond to him personally. This exhibit expands on that personal relationship by showing readers/listeners revealing elements about him never seen before. Visitors have a chance to learn more about how he envisioned and then charted his own legacy.”

Robert Israel can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

This is a revealing review of what promises to be a revealing exhibit. I hope the show does make it to a Boston area museum. Though if Trumpism continues to cast its dark shadow, a road trip to Toronto might be an option.