Opera Album Review: A Powerful New Recording of an Opera from the Terezin Concentration Camp

By Ralph P. Locke

I know no more thoughtful disquisition, for the opera stage, on basic questions of life, death, war, love, power, and resistance.

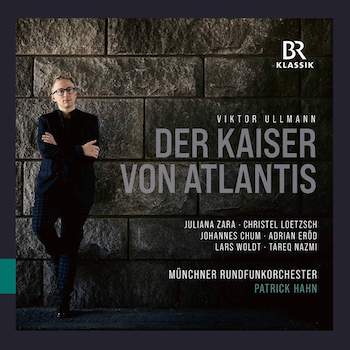

Victor Ullmann: Der Kaiser von Atlantis

Juliana Zara (Girl with Bobbed Hair), Christel Loetzsch (The Drummer), Johannes Chum (Harlequin), Adrian Eröd (Emperor Overall), Lars Woldt (Loudspeaker, i.e., P.A. System), Tareq Nazmi (Death).

Munich Radio Orchestra, cond. Patrick Hahn.

BR Klassik 900339—53 minutes

To purchase, click here.

The Emperor of Atlantis has achieved a well-deserved reputation as one of the strongest works to have been composed by any of the several important composers who died in the Holocaust. Its composer, Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944), worked on it in Terezín (in German: Theresienstadt) around 1943, and even managed to get bits of it rehearsed before the Nazi authorities sent him off to the Auschwitz death camp. His score was kept safe by friends and eventually became the basis for performances (starting in 1975), a published edition, a revised edition (by Andreas Krause), and multiple recordings.

The Emperor of Atlantis has achieved a well-deserved reputation as one of the strongest works to have been composed by any of the several important composers who died in the Holocaust. Its composer, Viktor Ullmann (1898-1944), worked on it in Terezín (in German: Theresienstadt) around 1943, and even managed to get bits of it rehearsed before the Nazi authorities sent him off to the Auschwitz death camp. His score was kept safe by friends and eventually became the basis for performances (starting in 1975), a published edition, a revised edition (by Andreas Krause), and multiple recordings.

Briefly, the opera is a devastating commentary on the excesses to which unconstrained political power and a taste for militarism can lead. The libretto was written by Peter (or Petr) Kien, an immensely talented and prolific playwright and visual artist who was likewise incarcerated in Terezín (and ended up dying of disease in Auschwitz at age 25).

The characters are types, hence they are not given specific names. In this shortish work (which lasts less than an hour), Death decides to stop letting people die. Even those wounded in humanity’s insane wars — more specifically, the Emperor of Atlantis’s “war of all against all” — now remain alive indefinitely, in a state of endless suffering. At the end of the opera (well, at least in one of its several versions), the all-power emperor — a likely stand-in for Hitler — agrees to die so that Death will agree to carrying out its necessary tasks again.

Ullmann’s music is a heady mix of grim and playful, making allusions to hymn tunes and popular-music styles, with instrumental flourishes, propulsive rhythms, and sweet-sour harmonies that evoke, at times, such composers of his era as Hindemith, Weill, and Prokofiev but that, taken together, create a distinctive sound-world like no other. I find it hard not to be devastated whenever I hear this highly original and accomplished work and think about how its composer’s life — and that of millions of others — was cut short by the very lust for power that the work describes so effectively.

A few years ago in American Record Guide (January/February 2019) I praised a new release that had been recorded in 2015 and that was led by the Swiss-Argentine conductor Facundo Agudin. The Agudin recording used Krause’s recent critical edition, and the performance seemed to me admirable, though not finer than the by-now-classic one conducted by Lothar Zagrosek and featuring such major singers as Walter Berry (as Death) and a resplendent Iris Vermillion (as The Drummer). On the Fagudin recording, one immensely effective singer, Vasyl (or Wassyl) Slipak, took two roles (Death and The Loudspeaker). Slipak was an astoundingly talented bass-baritone who, a year after the recording was made, volunteered to fight the Russian-backed insurgents in Donbass and was killed by a sniper.

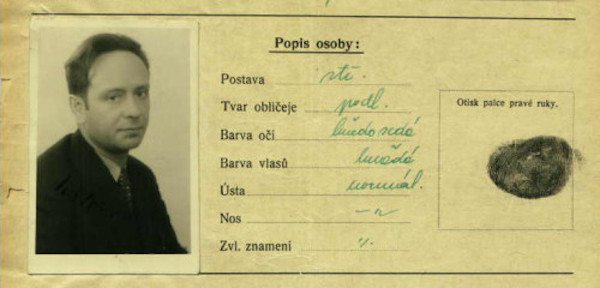

Composer Viktor Ullman’s identity card.

This latest recording was made during an unstaged (or minimally staged) performance in front of an audience, and it is wonderful — perhaps even better, at times, than the Zagrosek. The cast members all have steady and healthy-sounding (young?) voices. Often, indeed, they sing with astounding beauty of tone, which helped keep my ear glued to the proceedings, whereas I have sometimes felt that I was being shouted-at in my contacts with the work (on recordings and in live performance). The all-crucial words are rendered clearly and idiomatically by all concerned. I cannot resist praising Tareq Nazmi. Born in Kuwait, he received his training primarily in Munich and has been highly praised for his operatic performances in operas from Mozart to Britten. In 2020 he sang the role of Colline in La Boheme at the Met.

The microphone setup must have been elaborate because everything comes through with clarity. Some fresh choices are made: for example, we get a harpsichord instead of what sounded like a piano with thumbtacks in the Agudin recording. I wish that the essay, which is otherwise informative and thoughtful, had described and explained what decisions were made about orchestration and about passages that exist in alternative versions.

There is a detailed summary but, alas, no libretto. But you can probably work with an English translation that can be found online. The handwritten full score can be seen here. In short, this new release rises to the top, even challenging the wonderful Zagrosek recording. I know no more thoughtful disquisition, for the opera stage, on basic questions of life, death, war, love, power, and resistance.

And, alas, the work seems now to be more prophetic of events and ongoing threats in our own day — here at home and in many lands — than anybody would have guessed when it was unveiled to the public at its belated premiere in Amsterdam in 1975.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Munich Radio Orchestra, Patrick Hahn, Ralph P. Locke, Tareq Nazmi, Terezin Concentration Camp, The Emperor of Atlantis