Film Review: William Kentridge’s Wondrous “Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot”

By David D’Arcy

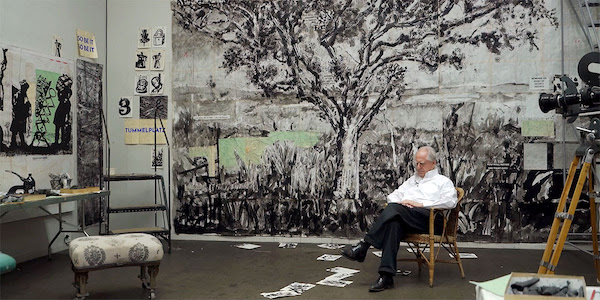

The nine-part film series focuses on the artist in his studio in Johannesburg. We see William Kentridge as he draws, paints, designs, paces the floor, and thinks out loud — among other things.

A scene from William Kentridge’s Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot.

Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot is a nine-part television series created by the South African artist William Kentridge. Three parts of the project recently premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, screening as a stand-alone film of 110 minutes. See it when you can. As of now, the series has no streaming date. The film project focuses on the artist in his studio in Johannesburg. We see him as he draws, paints, designs, paces the floor, and thinks out loud — among other things. Conceived and produced during the Covid epidemic, this is a personal work. It couldn’t help but be, given that it was created under conditions of quarantine. It’s also political, as we might expect from a man whose life in South Africa has been shaped by the country’s injustices.

(The MFA Boston has 20 works by Kentridge — 18 prints, one video, and a set of ceramics. None are on view at the moment. A Kentridge retrospective has just opened at the Royal Academy in London.)

The project was launched when Kentridge found himself — alone in his studio, walls covered with pictures, including that of a coffee pot — dealing with a South African quarantine that he describes as strictly enforced. He never wrote a script for the series, but he had plenty of time to film it. That sounds like a recipe for a standard one-man show, with the studio and its walls serving as a stage.

Kentridge’s solution was to film two simultaneous versions of himself, projected together on the same screen. The strategy turns the predictable monologue in isolation into a dialogue that shifts back and forth. The probing exchanges range from discussions of 18th-century French philosophy to repartee about or reenactments of the gags — vocal and physical — of classic film comedians such as Laurel and Hardy. You’ll recognize a move or two borrowed from Groucho Marx. Yes, the artist can be funny, very funny. He can also be witty and conceptually ambitious as he serves up a paradoxical mix of allusions, self-quotations. And there are some stunning visual surprises along the way.

You won’t lose sight of the coffee pot, as an idea or as an image. It’s on the wall the entire time.

Kentridge, now 67, has worked with moving pictures for years, often animating his own drawings in short films that observe or recall his country’s racial anguish. (His father, who is still alive, was a lawyer who defended opponents of apartheid at a time when the regime was hardening its grip.) This time the subject has been dictated, in part, by circumstances: it is about the artist making art in his studio.

Three episodes pulled from a larger work inevitably leave us with gaps. I interviewed Kentridge to fill in a few of the blanks. He explained his reference to a coffee pot.

“Over the years I’ve used the same Moka pot as an emblem and sculpture, and done many drawings of it. There’s something about the architecture of the pot that is quite anthropomorphic — the skirt, narrow waist, wider shoulders, and the head of the Moka coffee pot. It’s simply saying that one way of describing who one is as an artist is through all the things that you’ve made. So it is a kind of indirect metaphorical self-portrait, the coffee pot. There’s a section in the film where I say, you could do a self-portrait with all the things that you’ve drawn in your life, the same way you can say that someone’s self-portrait is all the books that sit behind them in the bookshelves that they’ve read. These are ways of describing who someone is. So the coffee pot is saying that the way of thinking of the self is wider than a drawing of the self.”

“I suppose the central metaphor of the studio is thinking of the studio as an enlarged head,” he observed. “All the thoughts in your head being enlarged into all the drawings and the objects on the walls in the studio and between the studio are the movement of thoughts around your head, from memory to imagination to unconscious to conscious — all of those as movements across the studio.”

“And between multiple selves,” Kentridge added. “That kind of splitting is something you’re aware of in the studio,” he explained, “but it’s not just about the studio. It’s a human phenomenon — being yourself and stepping back from yourself.”

A scene from William Kentridge’s Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot.

Self-Portrait is not a documentary, Kentridge stressed. There is no story. There are stories, often overlapping, sometimes seeming to appear from nowhere, as in the case of stop-animation “mice” made from cast-off paper, who roam the studio in the dark. Maybe one of the remaining episodes will take up the idea of why “vermin” haunt his work. Some of the stories we hear deal with his childhood, and the picnics that his family would take. Kentridge argues with his double (who sounds more and more like a brother) about what their mother prepared for them to eat.

All the while, Kentridge is drawing and painting. Anyone who has seen his work will know he has a rare virtuosity with charcoal, a medium whose smudge and infinite shades of gray feels tailor-made for South Africa’s dark history. He draws like a magician, applying it and then erasing it, aided by rapid-fire super-imposition of version upon version of the same image. In one scene, he and his double draw landscapes simultaneously — one is of a wooded glen that seems to be borrowed from European art history, the other is of a barren expanse somewhere around Johannesburg, a mining town which for much of its history was surrounded by yellow mountains of waste from gold excavation. These mounds were finally removed — but only after a process was developed to extract remnants of gold from the waste. He notes that a Johannesburg grande dame advised the mining elite to create an art museum, so that the city’s gold barons might be remembered for something more than shoveling gold out of the ground and shipping it to London.

A scene from William Kentridge’s Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot.

Wide-ranging and filled with Kentridge tropes (parades in silhouette, smudged portraits, animated figures exhumed from the surrealist ’30s, grim images from South African history), Self- Portrait taps into the revelatory spirit of Kentridge’s 2012 Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard University Those talks included examples of animation and multiple Kentridges on film. There were also musical performances, with the artist narrating as conductor or ringmaster. In Self-Portrait, a decade later, the theatrical turns are fully staged — dramatic versus concert performances.

And it all provides an inspiring glimpse into the artistic imagination of a man rooted in drawing who is also eager (at least in these three episodes) to deploy as many other media as possible. Three editors in Johannesburg worked on Self-Portrait, plus Walter Murch (Apocalypse Now, Godfather III, The English Patient, The Talented Mr. Ripley, etc). Kentridge says that Murch, as consulting editor from afar in London, played an active role. Whatever the division of labor was among the elder Murch and the three editors in South Africa, the resulting synthesis is wondrous. Somehow I suspect that Murch played a crucial role in making that teamwork possible. That guess, I note, is based on seeing three episodes.

I had the chance in Toronto to see Self-Portrait in a theater with excellent projection, which made me hope that the series won’t be released only as a streaming program. Kentridge’s art overflows with nuances, and one way to appreciate them is to have the ability to rewind, and rewind again. This way you’ll see everything, from the careful shading of the charcoal to the anthropomorphizing of the coffee pot in the title (which many will see as an homage to Giorgio Morandi), from the physical comedy of his multiple selves on screen to the musicians and dancers (a self-satirizing Kentridge included) who enter the studio once Covid rules are relaxed. That said, it was a delight to first watch the miniaturized Self-Portrait on my computer. It was an even greater delight to see it on the screen. Bring on the next six episodes. There will be much more to say.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Wonderful article David!