Doc Talk: American Dreams, North and South, in Films by Abigail Disney and Patricio Guzmán

By Peter Keough

In their recent films two disparate documentarians — Abigail Disney, the scion of the legendary Hollywood mogul, and Patricio Guzmán, exiled Chilean socialist — investigate the past, present, and future of their nations’ essential illusions.

The American Dream and Other Fairy Tales is screening at the Kendall Square Cinema and is available online. Go here.

My Imaginary Country screens at the Brattle Theatre September 30-October 6. Go here.

The Battle for Chile Parts 1-3 screen at the Brattle Theatre October 1. Go here.

A scene from Abigail Disney’s The American Dream and Other Fairy Tales.

In their recent films two disparate documentarians — Abigail Disney, the scion of the legendary Hollywood mogul, and Patricio Guzmán, exiled Chilean socialist — investigate the past, present, and future of their nations’ essential illusions.

Who wouldn’t want Walt Disney as their great-uncle? As a child watching him host his TV show Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color I certainly would not have turned down a chance to call this genial, kind, and seemingly all-wise mage Uncle Walt. In The American Dream and Other Fairy Tales his great-niece Abigail admits how privileged she felt as a child to be part of the Disney tradition. Disneyland, where she is seen beaming as a child in clips from archival super 8 movies, seemed a second home.

But the philanthropist, progressive activist, and producer of such enlightened documentaries as Pray the Devil Back to Hell (2008), The Queen of Versailles (2012), and Citizen Koch (2013), has long had mixed feelings about the benefits, clout, and fortune she has inherited. Nonetheless, until lately, she has been unwilling to speak ill of the family business. She is proud of all the joy that Great Uncle Walt and her grandfather, Walt’s brother and partner Roy, have brought to the world, not to mention the version of the American Dream of pulling oneself up by one’s bootstraps that they promulgated and supposedly embody.

Those illusions could no longer be sustained in 2018 after she encountered Disneyland employees working multiple jobs and still unable to make ends meet. She learns that Bob Iger, CEO of Disney, was earning $65 million a year, around 2000 times the salary of the average Disney employee. Dismayed but without any authority to initiate change in the corporation, she responded by sending an admittedly futile email to Iger politely requesting that he do something about this obscene discrepancy. Receiving no satisfactory answer, she then resorted to taking her cause to Twitter and cable news and a frustrating appearance before a Congressional committee. There a callow Congressman from Indiana ignores all the points in her presentation and tells her that what she is demanding is nothing short of socialism.

Thankfully, Abigail Disney also decided to make this film and in it she points out — as she failed to do in her congressional appearance — the corporate socialism Disney itself enjoys when, for example, Anaheim spends a fortune building a parking garage for the resort, leases the property to Disney for a dollar a year, and then allows them to rake in as profit millions in fees, presumably tax-free. Or when a Disney employee making $15 an hour must resort to food stamps, thus forcing the government to make up the difference between the corporation’s inadequate salary and the actual cost of living.

Disney, the filmmaker and not the corporation, does look into the circumstances of the victims of this economic disparity. She checks in with a married couple who met working as janitors at Disneyland and now have three daughters. They must put in overtime in a desperate attempt to survive. A 30-something woman weeps because her American Dream of working at the “happiest place on earth” leaves her on the verge of homelessness. And a woman in her mid-20s still must live in her parents home and defer, seemingly forever, her dream of getting a college degree.

One wonders whether Disney, the filmmaker not the corporation, dipped into her own largesse to make things a little easier on her subjects. Or how many Disney employees might be victims of the MAGA scam, misdirecting their discontents from the fat cats exploiting them to the illusory bugbears of immigrants, minorities, cultural elites, trans people, critical racial theory, and the like.

Disney is relatively quiet about the Trump phenomenon but she does shed light on the process by which wealthy right wingers and corporate interest groups have been able to turn the working class away from the institutions and policies that benefit them and instead embrace an ideology that was toxic to their interests. She points out how back in the 1960s CEOs took in only(!) 67 times the annual income of their lesser paid employees and most corporate owners vowed to “decently make a decent profit.” Flash forward to the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s which depicted government regulation and social programs as the bad guys. Because of the country’s intransigent if unacknowledged racism, it didn’t take much to convince a lot of white people that these supposed helpful government measures served only to blight a healthy free market economy in order to benefit lazy Black and brown people and deprive hard-working white folks of the benefits of Milton Friedman’s “trickle-down economics.”

Abigail Disney’s response to the latter is basically “don’t trickle down on my leg and tell me it’s raining.” But the film as a whole lacks the fire, pathos, and eloquence of her previous directorial effort, the brilliant The Armor of Light (2015), and I fear its impact may be slight.

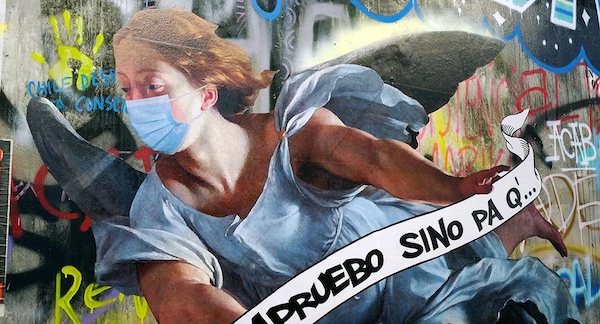

A scene from Patricio Guzmán’s My Imaginary Country.

Meanwhile, some 5500 miles south of Anaheim in Santiago, Chile, octogenarian Patricio Guzmán begins his new film My Imaginary Country in the city where on September 11, 1973, he had been held prisoner with thousands of other detainees in the National Stadium. General Augusto Pinochet had just overthrown the constitutionally elected government of Salvador Allende and his reign of terror had begun.

Guzmán had been recording on film the events leading up to the coup in what would become his three-part, five-hour documentary The Battle of Chile (1975-79). It’s a heartbreaking, infuriating, and revelatory account that begins with the ecstatic success of a socialist democratic government and ends with its crushing defeat at the hands of a US-sponsored military coup culminating in the apparent suicide of Allende.

Now, five decades later, he once again finds dislodged paving stones littering the streets, thrown by demonstrators protesting the disparities and injustices that persist in the country. Though Pinochet himself was ousted by a plebiscite in 1990 after 13 years murdering, torturing, and imprisoning thousands while uprooting the country’s vestiges of freedom and democracy, the constitution instituted by his regime remained in place. But in October 2019 a public transportation fare increase inspired high school students to begin a campaign of jumping turnstiles as a means of protest. From that unlikely, spontaneous beginning spread a movement that would stir millions to demonstrate for reforms in education, health care, for economic and political justice, and for a new constitution.

Unlike the predominantly male revolutionary cadres seen in his earlier documentaries, this time women have taken up a dominant role in the movement. Fed up with patriarchal oppression and violence, they are invested with fierce and courageous resolve. In between sequences recording clashes between demonstrators and the increasingly brutal police and military responders, Guzmán profiles some of the women leading the way. They are students, journalists, mothers, and workers. The divisive abstractions of ideology do not drive them this time around but raw emotion — frustration, anger, and a vision of a better future.

Their perseverance and courage pay off in 2021 when an overwhelming majority of Chileans vote to draft a new constitution and a convention is established to do so. Guzmán is further encouraged when later that year Gabriel Boric, a 35-year-old former student leader and constitutional agreement negotiator, is elected president, soundly defeating his far right opponent. By the end of the film Guzmán dares to wonder if the country of his imagination might soon be a reality.

But as it happens, he might be right to wonder. Just weeks ago on September 4 after an apparent right-wing disinformation campaign, the draft of a new constitution was rejected by voters. Renewed efforts to draw up an acceptable version continue. The lesson of ecstatic dreams crushed by treachery and disaster related in the earlier films lingers. Not just for Chileans, but for North Americans too. The deceptive progress and cruel reversals depicted in them uncannily evoke some of the events we live through today as we approach yet another all-important election.

Despite this, and though this new documentary might not have the agitprop rawness and urgency of the three earlier Battle of Chile films or the poetic profundity of his second Chilean trilogy — The Cordillera of Dreams (2019), The Pearl Button (2015), and Nostalgia for The Light (2010) — My Imaginary Country offers something perhaps more precious and fragile: hope.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

I also wondered if Abigail Disney gave a bit of money to those she interviewed, at least after the film was finished. According to the Internet, she is worth 150 million dollars! And thanks for the Guzman piece. I can’t wait to see his latest film as I need help unraveling what is happening now in Chile.

Thanks. Chile seems more hopeful than here at the moment.